Editor’s note: Fandor features Computer Chess as a new streaming release this week, and Keyframe resurfaces two earlier Bujalski interviews to celebrate it. The following interview was originally republished on the occasion of the Kino Lorber release of the remarkable movie at Film Forum in New York. Hannah Eaves interviewed filmmaker Andrew Bujalski in 2006, and recorded the conversation while Bujalski was starring in Joe Swanberg’s Hannah Takes the Stairs. Literally. A second interview (“Bujalski Now”), a Computer Chess-centric conversation between the filmmaker and Jonathan Marlow, accompanies it.

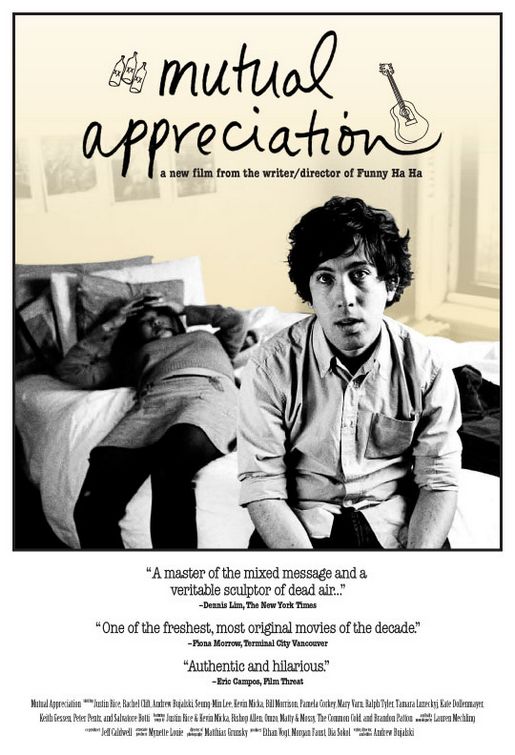

Hannah Eaves: You’re self-distributing Mutual Appreciation with Houston King. Had you always intended to self-distribute or would you rather have had a distributor?

Andrew Bujalski: We certainly were casting about to get the film out there via traditional distribution. As much as there are many things that are great about self-distribution—it’s great to have that kind of control—it’s not something I’d really like to do unless it seems like the best way to go. I mean it just takes up too much time, from my perspective. I’d much rather leave all that stuff to somebody else. But the only kind of offers we were getting were just so financially disadvantageous that we decided self-distributing was the much wiser way to do it, even though it’s not my idea of fun.

Eaves: And have you had any interest in anyone funding any future productions for you?

Bujalski: Possibly. We’ll see. I’ve written something that I’d like to do next year and I’m hoping I’ll be able to pull that off, but I have no idea what the next year will bring.

Eaves: So, you studied at Harvard. How much of that was a practical education and how much was theory?

Bujalski: You had to do both kinds of classes to graduate, but the practical stuff was really where my heart was. I don’t particularly remember the theory classes all that well, although I do remember all the great films that I would see for those classes. But the filmmaking classes made a big impression on me and, I think, had a huge impact on how I’ve learned to work since then. Harvard’s program has a really strong documentary background, and so learning to work in that style—learning to really hand-make films and work in that vérité fashion—I’ve applied a lot of that to how I try to make fiction films.

Eaves: And were your short films at school similar in tone to the work you do now, or were they documentaries?

Bujalski: Both. I did some documentary stuff and then, I guess, two little fiction films, which I don’t really need to ever see again. I’m happy to have them buried under a rock. But I learned a huge amount from doing them.

Eaves: And what did you learn from them?

Bujalski: I guess I came out of there with a real desire to correct what I felt were the mistakes of those films. The writing was not so great, but really I felt like I didn’t know how to make or to find interesting performances. That really became the rallying cry on the features, just to make that a top priority. I’ve always felt like maybe the greatest lesson, or the most consistent, inconsistent truth of filmmaking I’ve learned is that it’s surprisingly difficult, but really crucial, to try and understand the footage you have, as opposed to the footage you want. I think so much of bad student filmmaking, or bad non-student filmmaking, comes from people who have the visions in their head, and you just have to do so much work to accomplish that. Sometimes it’s very easy to lose sight of the fact that the material you’re actually getting bears no resemblance to the vision in your head. You need to learn to grapple with what’s actually there, whether you like it or not. That’s what I’ve tried to learn how to do, although I don’t think it ever stops being a challenge.

Eaves: It’s funny you say that because I was speaking to François Ozon recently and he was saying something almost identical about having to confront the difference between what you’ve imagined in advance as a director with what you actually have filmed, and how sometimes that can be a good challenge.

Bujalski: Ultimately, I think that’s part of the excitement of working in this medium. I occasionally fantasize about being a novelist or something that’s less stressful in just the pragmatic way of all the thousands of things that you have to get done, but I don’t think I could do it because I don’t think I have the stamina to stay in my own head that long. That’s part of what’s so exciting about making a film. It’s that you do grapple with the real world. Even though the real world throws punches at you, it also gives you things that are much richer, more interesting certainly than you could ever put in your screenplay.

Eaves: I think what you’re talking about with performance in student films, and even non-student films is also exacerbated by bad writing. How much of that do you think is in the writing? I’m thinking of your performances and how, in contrast, they seem so natural.

Bujalski: I think that, on some level, the performances in my films are as stylized as anybody else’s. But, yes, I think writing has a huge impact on how it turns out. It’s hard to quantify what comes from writing and what comes from the moment. And it’s really important to me to try not to be too precious about the script and yet I couldn’t imagine working without a script. Some people are able to do that and to get a lot of loose stuff out of that. But I guess I’m more and more aware of how important it is, even for me as a director, to have a sense of what structure is underlying everything. Then, on top of that, you can go as weird and outlandish as you want. But that’s certainly been that pattern of the films I’ve done so far… hang on… [speaking to someone else] You’re not going to… what are you doing? Should I be here? Okay. Are you there, Hannah?

Eaves: Yes I’m here, go on.

Bujalski: I think I might actually be being filmed. Now. As I speak to you.

Eaves: Oh, really?

Bujalski: Yeah. So I’ll try to look extra handsome while I do this (if you’ll forgive an additional layer of self-consciousness).

Eaves: We were talking about scripts and how it was important to have that backbone.

Bujalski: When I write, I try to be really as precise as I possibly can. Like David Mamet makes sure that every piece of punctuation is as perfect as he can make it. Then, of course, once we get to the set, all of that gets thrown out. But somehow that’s really helpful for me to feel like I know the blueprint of the work and I think it helps the actors.

Eaves: Do you get feedback from the actors before you arrive on set or is it mostly that the changes happen in the performance process?

Bujalski: A little bit of both. We haven’t had a lot of time to rehearse just because people are non-professionals and they do have real jobs. It’s not like we can really workshop things for a long time. You try to figure it out as you go and then, of course, the bulk of the work happens when you’re on set.

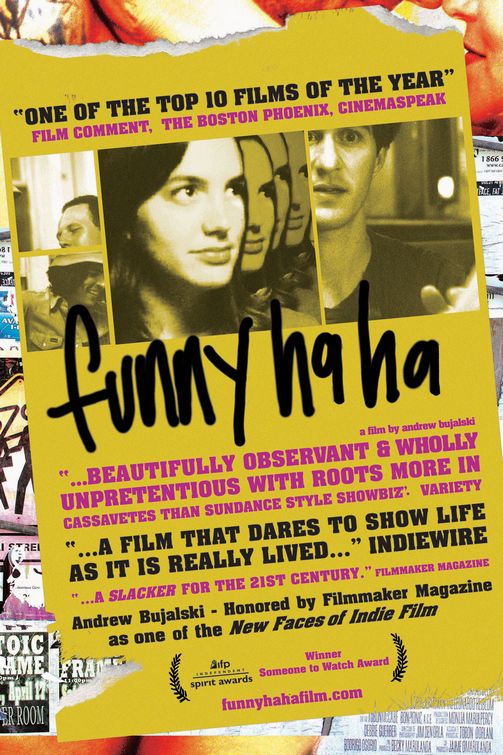

Eaves: Now what was the position you were in when you were writing Mutual Appreciation? You had just finished Funny Ha Ha and were starting the distribution phase of that, right?

Bujalski: Yeah, well, Funny Ha Ha had a really long, strange life-span, so for the first six months after I finished Funny Ha Ha, it took me that long to get anyone to screen it anywhere. That was when I wrote most of the first draft of Mutual Appreciation, which was great, in a way, because I wasn’t so subsumed into the whole world of promoting and running around, which has been, you know, a lot, a lot, a lot of my time in the last couple of years and I’ve probably overcommitted to that.

Eaves: How have you managed that? I mean, it must be very difficult to spend so much time traveling with a film when it’s not generating that kind of income…

Bujalski: It’s a mystery to me how I’ve survived this long. At the moment, I just got my first ever Hollywood job. I got hired to adapt a novel, so that’s what’s paying my rent at the moment. And then teaching, and then I’ve just had a lot of little day jobs here and there and somehow managed to string it together. When you go to a film festival, you usually get a few free meals out of that. [Laughs.]

Eaves: And what has the film festival reaction been to Mutual Appreciation? Has it been different than for Funny Ha Ha?

Bujalski: Similar, although I sort of know those ropes now and, of course, we had a much better time getting Mutual that initial traction. Funny Ha Ha, again, had that strange long build time. We started at smaller regional festivals, but it just kept going in a way that we hadn’t predicted. With Mutual, there’s been a little more interest from the get-go. And then we started getting into international film festivals, which is something we had not done with Funny Ha Ha.

Eaves: You’ve gotten a lot of really great press for Mutual Appreciation, too. I have to wonder if that’s gratifying or frustrating, considering you haven’t had any large distributors come on board…

Bujalski: I don’t know, it doesn’t bother me that much. When we were making it, I wasn’t thinking we were going to make money off of this or this was going to get traditional distribution. I have a contrarian streak; something feels kind of badge-of-honor-ish about not fitting into the commercial marketplace.

[Background: ‘I’ll be over here!’]

And nice reviews are great. In a way, I’m pretty certain that part of the reason that we’ve had such a good response from the press has something to do with where we are or where we aren’t in the commercial marketplace. I wouldn’t expect such kindness from the press if we were making any money. [Laughs.]

Eaves: What? Come on, it’s a great film!

Bujalski: I don’t know!

Eaves: It’s like you’re saying that making money and making a good film are mutually exclusive ideas!

Bujalski: Oh, no, that came out… that sounded a little bit cynical. What I meant is that I do feel like we’ve been adopted by certain critics. They’ve adopted us and I think the underdog bit has to do with that. Maybe I’m not giving critics enough credit there.

Eaves: I think that critics are just happy to see a film that they actually like and can write good things about. Because I don’t think that comes along that often.

Bujalski: Right.

Eaves: So, going back to the film. How did your friendship with Justin Rice come about? How did you know each other?

Bujalski: We went to college together. And then, the year after I graduated, we ended up being roommates. So that was, I guess, when we really got to know each other.

Eaves: And so when did you decide that you were going to write a film that would have him as a central character? Was it after seeing his performance in Funny Ha Ha, or was it already in your mind?

Bujalski: I don’t remember exactly. I can’t really focus on two things like that at once; I wasn’t thinking too hard about another film while we were still making Funny Ha Ha. But I do think that after doing that scene and having fun doing that, I had it in my head that there was a funny movie to be made with him in the lead.

Eaves: One of my favorite scenes is when Justin is drunk at a party with those three girls. I know from other interviews I’ve read that you’re sick of being compared to Cassavetes, but I couldn’t help but think of him in that scene in particular. Was that scene always in the script as it stood? It has such a great feeling to it.

Bujalski: I wrote the scene. That scene changed a lot. It got this great energy from the shooting, but… Part of the inspiration for the film was, what was a funny film that could be made with Justin in the lead? And I liked the idea of Justin among a stronghold of women. There was something funny about that, so that scene was maybe the apex of that notion. And, structurally, we really do stick to the script pretty closely. I don’t think there are any scenes—I mean, there are tons of little moments in scenes and inventions in scenes—but I don’t think there’s any scene in the movie that’s not in the script in some form.

[Much background noise on the ‘set.’]

Eaves: There are a few scenes in the film where people have to be honest about things, particularly how they’re feeling and what they’ve done. And the filmmaking itself seems very honest in a way. Do you feel like honesty both between your characters and towards the audience is important?

[Background: ‘He won’t like it.’ Laughter.]

Bujalski: Sorry. What was that last part again?

Eaves: Is honesty an important part of filmmaking for you? I mean, the characters are very honest with each other.

Bujalski: They’re trying to, they’re trying to, they’re making the effort.

Eaves: But it’s also about honest portrayals in that the actors’ performances are very honest.

Bujalski: It’s a difficult thing. Particularly when you’re working with non-professionals and you’re not asking them to transform themselves. You don’t want to make them uncomfortable, to reveal more of themselves than they want to. But, by the same token, you need honesty in the performance and that’s something that every one of the actors has to figure out. It’s a difficult thing and it’s also hard to talk about. But I think any kind of filmmaking is a combination of truth and lies and sometimes the thing that seems most honest in the film is the most invented.

[More background noise.]

Eaves: Sorry, I’m kind of distracted because of the…

Bujalski: I’m distracted too.

Eaves: It’s a bit of an awkward situation.

Bujalski: What was that?

Eaves: I said ‘It’s a bit of an awkward situation!’ Just because so much is going on for you right now.

Bujalski: Yeah, I think they’re making a short film about making fun of me being interviewed. I can’t tell. And I’m trying to give you my full attention.

Eaves: I felt that Mutual Appreciation was a big step forward for you, from Funny Ha Ha. I don’t know if other people have expressed that to you. Is that something you feel aware of? Is it something that just comes with experience, do you think?

Bujalski: It’s hard to say. You know, a film’s like a snowflake and all that, so I don’t see it necessarily as a progression. I think every film is a wild leap into the void and you don’t know what you’re going to come out with. So who knows? I mean, it’s probably the hardest thing for me to see because you just have the tunnel vision of working and you don’t really know what you’ve done differently or what you’ve done the same or what was due to your intervention and what was due to luck. Who knows? If I can make ten more then maybe I’ll see a pattern.

Eaves: Right, all you can ask is, ‘Is it a progression or an oddity?’ You can’t work it out yet.

Bujalski: Exactly.

Eaves: I saw you interviewed Caveh Zahedi for Filmmaker Magazine.

Bujalski: Yes. Exactly. We had met a few times before. He has been very kind to me. I mean, he was the one who they asked, ‘Would you like anyone to interview you?’ And he put me on that list, which was great. But I’m not an interviewer and I was acutely aware of not doing a very good job. Being on your end of it. I would make long statements to him about his work and then I’d kind of say, ‘Right?’ Or, ‘What do you think?’

Eaves: I don’t know if, as a filmmaker, it would be different to interview another filmmaker rather than just as a journalist interviewing a filmmaker. Did it make you more self-conscious about the things you were asking?

Bujalski: Well, especially having been asked a lot of those questions. For better or worse, I think I’m a little burned out on this process of answering these questions and then to be the guy who was asking them made me feel like, ‘Oh, shit, I don’t have anything better to ask either.’ There’s something humbling about that.

Eaves: Well, documentary filmmakers, I think, can stay really passionate about their subject. I think it’s harder for narrative filmmakers to come to terms with the idea that they’re going to have to be analyzing and ‘anecdotalizing’ their filmmaking process for the next year after they’ve made the film.

Bujalski: Right. Or two or three or four years. I did another Q&A for Funny Ha Ha two weeks ago. Just because now it’s traveling to international film festivals where it’s never been and it feels silly to be held accountable for something that I started writing in 1999. I do envy documentary filmmakers that because you watch their Q&As and the Q&As are all about the subject and it’s not about so much the process. It’s a) boring to tell the same stories again and b) I am superstitious about it. Because you get forced to put forth a philosophy of filmmaking (which you didn’t necessarily have) and I worry that that jinxes you when you actually try to make the film. You’ve been spouting philosophy for so long that it has almost nothing to do with the practice of it, ultimately.

Eaves: So you’re haunted by what you’ve said in the past?

Bujalski: Right, and instead of figuring it out…

[Background: ‘Action!’]

…you fall back on your Q&A answer.