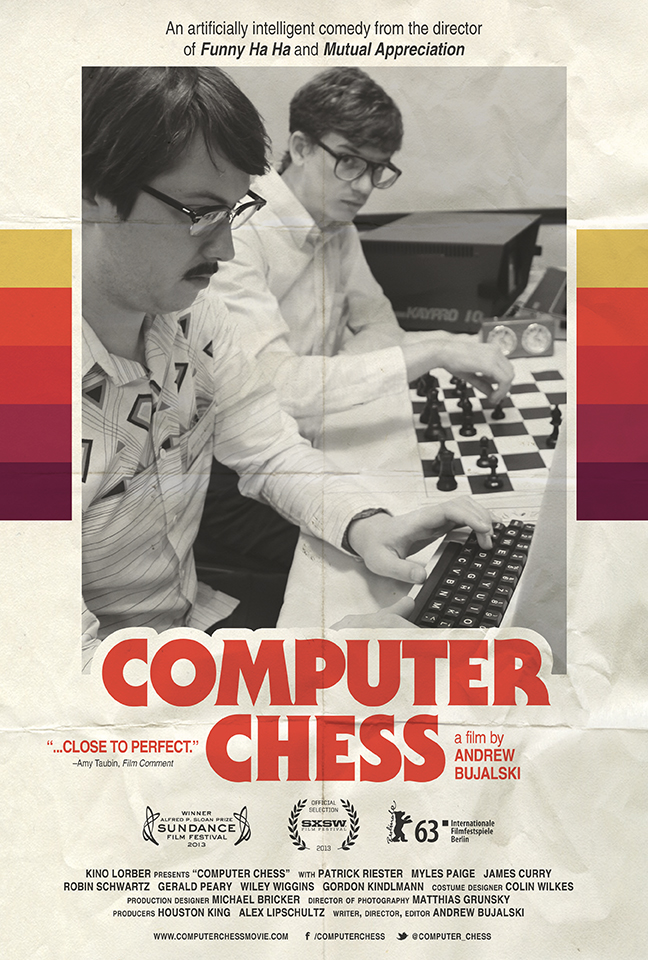

Streaming now: Andrew Bujalski’s extraordinary Computer Chess. Also on Fandor (as it has been for quite some time): Beeswax. You should see them both. But first you could read this. If you want.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in July, 2013.

Jonathan Marlow: Long time no see. Well, actually, we last saw each other in March.

Andrew Bujalski: That’s right. Yes.

Marlow: I don’t want to take up too much of your time [Bujalski was in New York to introduce the first few screenings of Computer Chess at Film Forum]. But I did want to get something up to cover the space from when we last did something like this [when Hannah Eaves interviewed Andrew Bujalski in 2006]. I want to just start at the beginning as a bit of preamble and then how we got to the present. Or, rather, how you got to the present, because I don’t factor very importantly into this equation. Way back when you made Funny Ha Ha, I’d argue that it was a relative low point in independent film. Caveh Zahedi mentioned Funny Ha Ha to me and I suppose, if it had been just about anybody else [unless that someone is Tom Luddy, for instance], I would’ve said, “Sure. Whatever. You saw a film that you liked. That’s great.” But for Caveh to say something about a film, it was unusual. I sought it out and, of course, as we all know, it’s great. We first met a little bit later, along with Houston King, when you premiered Mutual Appreciation. That leads to Beeswax, your first film to be made in Austin. More about that later but it is [plug] available on Fandor thanks to our partnership with Cinema Guild. With Computer Chess, you used U.S. Artists as a crowdsourcing mechanism. There was a tier in that campaign….

Bujalski: Thank you, again, by the way, for your help there.

Marlow: Delighted to help. There was a tier where there was an option to have a character in the film named after you. It was compelling but it also seemed unnerving, in a way, I suppose because I’ve had many different names over the years. I wasn’t even certain which name I would want to use.

Bujalski: How many names do you have?

Marlow: Too many. In any event, it was tempting but I didn’t do it. However, the first thing that happens in the film was a reference to someone named Robert Lawrence. Where does that come from?

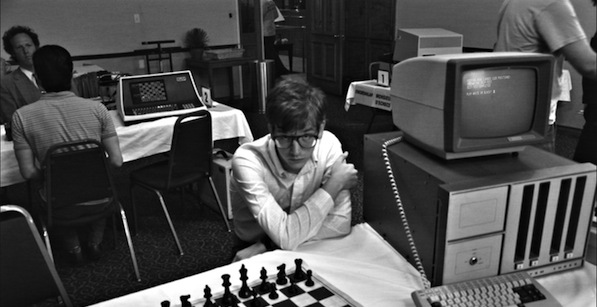

Bujalski: That name? Honestly, that opening sequence is one of the great miracles I’ve ever been witness to on a movie set. We had what I think was the greatest cast of extras ever assembled. We tried to find real chess enthusiasts, real computer enthusiasts and we were able to do tons of hard work by the folks who were in charge of casting extras. They really hustled and got all these great guys to come down. We were shooting this stuff in the Truman Hall and that basically was documentary footage and we just kind of turned the camera loose and we said, ‘Okay, guys. Now we’re going to go around and interview you.’ These were our extras and they had really no preparation for improvising in character. If the camera was on one guy and the guy next to him knew that the camera was coming to him, that guy would be on his iPhone looking up information on computer chess to work into his interview and that stuff was amazing. It was unbelievable. There’s no reason it should’ve turned out as well as it did. But we just had these brilliant guys in the room. They all had name tags (which our art department had made) and I think I had just made a list of a dozen or twenty names that I wanted to see on those name tags. But at some point my list ended and the art department just came up with more names to fill in on those name tags. Robert Lawrence, I think, was just the name that this extra had been assigned. All of which is to say that the short answer to this question would be, ‘I don’t know where that name came from. But it’s a good name.’

Marlow: I thought so, too, because that was the name I went by in high school. [Laughs.]

Bujalski: Really? There you go. That is uncanny.

Marlow: It was such a disorienting thing, seeing the film for the first time and having this notion in the back of my head. ‘I really should’ve opted for the naming tier. I really should’ve done that.’ And then one of the first things said in the film is that name. ‘What the hell?’

Bujalski: That’s truly uncanny. That’s amazing.

Marlow: As you’ve already noted, the casting in a film of this sort is extremely important. I can’t imagine a better cast for this film. You’re very fortunate with some extraordinarily talented people. Some folks are acting in a film for the first time and, usually when you see a film of this sort, you can kind of gauge the difference between these levels of ability. But when you go from, say, Bob Sabiston and Robin Schwartz to Wiley Wiggins, there’s this great gap in experience in front of the camera. Yet it is not obvious at all. Everyone is performing in a unified way and succeeding in evoking the period.

Bujalski: All credit is due to all those folks. Of course, I’ve been inclined in all of these movies I’ve done to cast non‑professionals and people who either have little or no experience acting. But I’ve always taken pains to point out that experience or no, I’m always casting people who I think have tremendous natural talent for it and that those people still have to show up and do the same job that any professional actor does and with the same kind of challenge that they seem to do it masterfully. We’re just very lucky to find the right people. Casting is always terrifying because you’re always opening yourself up to the heavens and say, ‘Please give me a miracle.’ I’ve been very lucky to have had those miracles delivered when I needed them and I wish I could figure out how do that in the rest of my life.

Marlow: [Laughs.] Well, on some level, when you go back to Mutual Appreciation and Funny Ha Ha, where you actually appear in your own the films, contrasted with your appearances in the films of other filmmakers, whether it be Hannah Takes the Stairs or Goliath or Sorry, Thanks, has that experience changed your way of working with actors?

Bujalski: It’s an interesting experience, of course, to go on the other side of the camera and know what it feels like. I’ve been very fortunate in those, too. Pretty much every time I’ve acted for somebody else, it’s been someone I know. Nobody would be crazy enough to cast me if they didn’t already have a prior relationship or friendship with me. I’ve been very comfortable of all those people and it’s been exciting to feel like I’ve been in the hands of good directors or to be handled in a way that I appreciated. By the same token, I hate to say it but I think I did better as an actor in my own movies. Not because I’m a better director by any means but because I had so much on my mind and so many problems as the director of those movies that I didn’t really have any time to be self‑conscious as an actor. Of course, when you work for somebody else, they have all the problems and you can just sit around thinking about how fat you are and how bad of an actor you are. And that tends to throw you off.

Marlow: Did you have the opportunity to see the Pablo Larrain film, No?

Bujalski: I did, yeah. When we were shooting, I had no idea that anybody else in the world was trying to pull off a stunt like this. It was funny to me to hear that somebody down in Chile had something like this cross their mind. I liked the movie very much. But of course I was relieved to see that it felt aesthetically… we weren’t playing exactly the same ballgame.

Marlow: No, not at all.

Bujalski: I felt that they did a hell of a job there and I liked the movie very much.

Marlow: I know that you’ve mentioned elsewhere the influence of Stranded in Canton. I have only seen fragments of it. There are some pieces of William Eggleston’s film that appear in a documentary about the band Big Star [Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me] where the footage is used as a device to show Memphis of that period. There is an aesthetic that happens when you’re shooting on a video camera like the Sony AVC‑3260. It creates a layer of faux authenticity for taking the audience back into that period in which the film is set. Obviously, the costumes and the set design and the other things that you’re doing extend that effect as well. A lot of the apparent informality of the way it’s being filmed suggests that it is an actual document of the period (even for a narrative film). There are those similarities between what you’re doing and what No is trying to do for period narratives. But, as you say, they take that and go one way and you take it in a very different direction.

Bujalski: Sure.

Marlow: The technical challenges in such a circumstance can sometimes be daunting. Archaic equipment has a tendency to break down. I don’t suppose if you knew how difficult it was going to be to keep out-of-date equipment functioning from the very beginning, you would be less inclined to actually take on those challenges….

Bujalski: Of course, of course.

Marlow: …since making a film is already hard enough to begin with.

Bujalski: Yeah.

Marlow: Was it always a point for you that you were going to shoot it in Austin?

Bujalski: I think so. This was such a crazy stunt to do. We made the movie as cheaply as we could make it (which still ended up being a good deal more expensive than I’d initially hoped or planned). I want to phrase this right because I was certainly dead serious about it and obviously worked as hard and as enthusiastically on this as I ever have on anything. But still, by the nature of it, it had to be something of a lark, if that makes sense. It takes place in nowhere so we could shoot it anywhere. I guess, being the father of a small child, I might as well shoot it where I can see my kid every night.

Marlow: That seems very sensible. You also had access to….

Bujalski: That’s the other thing, too. Austin is by far the most supportive filmmaking community I’ve ever encountered. Yes, of course, I was very happy to draw on all the resources of that town.

Marlow: Right. You premiered the film at Sundance. I finally had an opportunity to see it at SXSW, even though I was at Sundance and I didn’t see anything at all (which is an all‑too‑familiar experience for me these days). Even at SXSW, I was only able to see a handful of things, one of which was Joe Swanberg‘s new film, which some folks claim to be his most accessible. I take that to mean that it has a higher proportion of recognizable actors. Coincidentally enough, Drinking Buddies is also opening theatrically right about now. Computer Chess, however, could be perceived by some audiences as divisive.

Bujalski: I thought it would be a lot more divisive than it was. I mean, I’ve actually been stunned so far by how warm most of the responses have been. Before we premiered at Sundance, I did not know if I was going to have to spend the next two or three years apologizing for this movie and I was quite surprised to find that there was an audience for it. Obviously, it’s not for everyone but the people who dig it don’t have too hard a time finding their way to it.

Marlow: I suppose Austin was going to be a receptive and supportive audience on a certain level, regardless, but it was encouraging seeing the SXSW premiere audience and their enthusiasm for the film.

Bujalski: Right now, everything feels great. It feels like the stars are aligning well for us. I make no predictions about whether or not anybody’s going to be there tomorrow. We’ll see.

Marlow: It’s rewarding to see an overwhelming positive reaction. People are embracing the film and embracing the weirdness of it.

Bujalski: My fear has instantly flipped over from being afraid that I have to apologize to, instead, being afraid that somebody was going to say, ‘Okay, do that again!’ Because I would have no idea how to do that.

Marlow: Right, right. Now when we look across these films, there is a desire from the earliest stages to try and pigeonhole the work. To try to characterize it as something that doesn’t seem accurate. I’m not going to invoke the inappropriate naming convention….

Bujalski: I know where you’re going.

Marlow: [Laughs.] Because I was mentioning Drinking Buddies in the context of Computer Chess to suggest that, even now, there is a desire for certain folks to try to draw some kind of parallels when those kinds of parallels are just absurd. They might say, ‘Oh, look. Joe Swanberg is going off in this direction and Andrew Bujalski is going off in another direction,’ as if this is some larger preconceived idea or strategy.

Bujalski: I’m mostly at peace with the nature of journalism. You’ve got to get the story out the door fast and you’ve got to try to make sense of something and, obviously, there’s value to it. It’s like any kind of system. As human beings, we want to find patterns in things so we look for them and we sometimes invent them and it’s useful. It just frustrates me, of course, when that feels like the beginning of the end of it. When everybody wants to dig at that same idea. There’s nowhere deeper to go.

Marlow: That’s a real problem. Though you’re still in the thick of the Computer Chess theatrical release, is there something radically different that you would like to do next? There was some time between Beeswax and this film; obviously, becoming a parent plays a part in that.

Bujalski: The radically different thing I would like to do next would be earning a living.

Marlow: That would be nice. That doesn’t seem unreasonable at all.

Bujalski: That would be nice. Trying to figure out how do that has never been something that’s intuitive to me so I really don’t know. Certainly, I’ve been putting more and more energy into trying to figure out something—anything—that might earn me a living. Inevitably, it seems to be my kind of career pattern that I have my head against the wall, trying to figure that stuff out and eventually you get frustrated enough with it (or an opportunity presents itself) where I run off and do something commercially disastrous again. Which is kind of, for better or worse, usually where my heart is. I don’t know. I certainly have those things that I’m working on one way or another, that range from trying to do things very much within the commercial system to stuff that is a little more independent. But something like this I was absolutely taking on with the plan of it not making money. Again, it’s kind of an irony that this may well be my highest grossing movie.

Marlow: It is interesting, when we roll back the time machine, that your lead actor in Beeswax, Alex Karpovsky, is presently experiencing the life‑changing effects of a popular television role [on HBO’s Girls]. Or your Hannah Takes the Stairs co-star Greta Gerwig is finding a bit of success these days as well. It is possible to make a living in this business but the opportunities are few and far between. It is interesting to see this trajectory where folks are making a living doing what they love. It just doesn’t seem to happen as often on the filmmaking side as it should.

Bujalski: Economically, it’s a disaster. But in spite of that, there are still these miracles. Every year, there are still a dozen movies—or maybe less than a dozen—but every year, there are a few movies that come out of nowhere and blow your mind. You wonder how anybody could’ve done it. I hope that’ll never go away.

Marlow: That’s part of the thing that is so exciting about watching Computer Chess. It was unbelievable that someone would make a film out of this material but it was similarly unexpected how wonderful the results would turn out to be.

Bujalski: Obviously, that’s a thrill to hear. It’s all I can ask that someone feels that way.

Robin Schwartz on Playing ‘Computer Chess’

Actors do not generally appear in these pages. But the circumstances around Computer Chess are unique and the cast is appropriately unusual, too. Given the opportunity, who wouldn’t want to talk to the femme non-fatale of the film, Robin Schwartz?

Jonathan Marlow: We’re off to the races. I talked to Andrew Bujalski yesterday. He was in New York for the premiere of Computer Chess at Film Forum. I wager that the publicity engine is not necessarily the thing that he enjoys most about filmmaking. That’s my guess.

Robin Schwartz: Yes. Which is maybe a good thing, right?

Marlow: I think it’s a good thing. One of the things that we discussed was how important casting is to the film. This mix of folks like yourself or Gerald Peary—people who are appearing in a film for the first time—and placing them alongside Wiley Wiggins and Chris Doubek and other actors who have appeared in a number of films. It is handled in such a way that it does not feel like there is an experience gap in the performances. It seems like everyone is part of the same world. That’s fairly impressive. How did you get cast for Computer Chess?

Schwartz: I was just at work editing a documentary. Somebody [Drew Xanthopoulos] walked by. He was an AC and I think he was also helping to do some producing on the side. He walked by and asked me if I would do a screen test. At first, I said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’ Then I decided I could do it if it didn’t take very much time. And so I did it and I just talked about the New Yorker and how much I loved the magazine and I love the articles. It was just the nerdiest thing I could think of that I’m obsessed with at that moment. Then, surprisingly, I got a call from Andrew to go do another screen test at some random apartment in South Boston. That was the first time I’d ever met him. I went there and it was three of us—me and Andrew and one of the producers—and we just sat there. He had me do an improv scene with him about trying to convince someone that it was completely irrational for them to believe that their computer program was actually thinking. Something similar to the scene between Patrick and I when we play chess against each other. It was awful. I thought it was the most embarrassing experience that I’d ever had. I just thought I did a terrible job because I had no idea how to convince him that he was off track. One, because I’ve never really played chess! When we were finished, I thought, ‘Oh, well. That was fun. I’m never going to hear from this guy again.’ But I guess it worked.

Marlow: You were familiar with Andrew’s films prior to all of this?

Schwartz: No! I’d heard about them but I hadn’t really had a chance to watch them. If I remember correctly, neither had Patrick [Riester], the lead. I think he’d maybe seen one.

Marlow: Not to spoil anything but [spoiler] there are an entirety of two women in the entire film. Well, there are a few others, but primarily two. I don’t want to say that it must have been an uncomfortable situation on the set but it presents a rather delicate balancing act for an actor. You’re presented in the film as rather meek but then you’re also an object of attraction for the characters in the film as well. That seems to be a strange position all around.

Schwartz: [Laughs.] Yeah. It felt that way. I think because I didn’t know the full script and because it was the first time for me. I had this weird feeling of being completely exposed. It made me feel shy and yet I was also in the spotlight. I think that it really is how Shelly feels. She’s not used to that attention at all and that’s exactly what it felt like on set. I wanted to hide in one of the hotel rooms. The best place to be was probably with the costumer.

Marlow: How do you see your role in contrast to Cyndi Williams’ character, which is constructed almost entirely as the opposite? She plays this rather carnal, very self-confident woman, as opposed to the character of Shelly, who is very reserved and quiet.

Schwartz: I think Shelly kind of wants to be that confident. It feels like she takes those steps. She ends up in the hotel room with the guys who are drinking and, when she goes to knock on Peter’s door, she tries to actually connect with him. In a lot of ways, she’s kind of excited by the world and excited by all of these connections but she’s still incapable of making that jump. She’s still better at communicating through the computer and through chess than she is at emotionally communicating. I think a lot of the characters in Computer Chess do this. They apply computer programming and strategy to their human relationships and that doesn’t necessarily work. I think where the similarity comes in between her and Cyndi’s character is that Cyndi is applying ‘sex therapy’ to her relationship and that’s not really working either. She doesn’t get what she wants from Peter. It doesn’t make her connect to him any better.

Marlow: It seems clear that there isn’t necessarily a strategy that would work with Peter, regardless of the direction from which it came! I think it’s important at this point to mention that when folks read that a film is populated—and I think it’s a misnomer by saying ‘non‑actors’—by first‑time actors, the assumption is that these roles are generally typecast. In meeting you in Park City [at Sundance] and talking to you again in Austin [at SXSW], it’s clear to me—correct me if I’m wrong though I doubt that I am—that you and Shelly are not the same person. You’re not the character in the film. You’re acting. I suppose there’s some aspect of that character that you share but you’re definitely more outgoing than Shelly!

Schwartz: Yes. That’s not me. No, no. Absolutely.

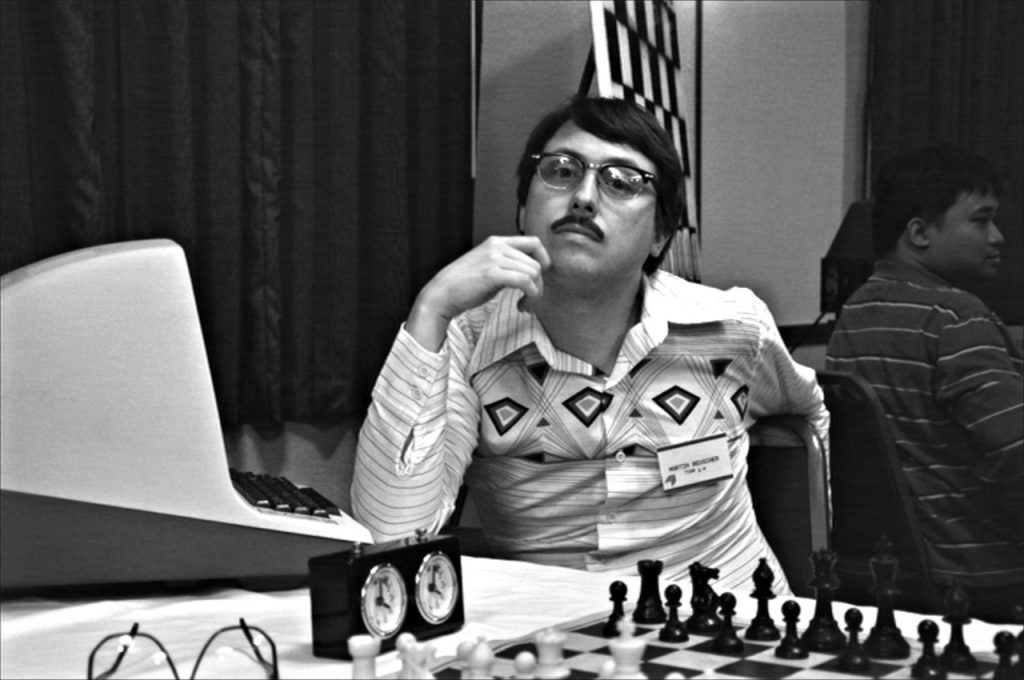

Marlow: You’re playing a character. As is everyone in the film. Gerald Peary is not Pat Henderson. Perhaps they share similarities but there are differences. Patrick is not Peter Bishton. They’re different people. Even Wiley Wiggins is a different person, enhanced perhaps by the mustache. The performances and appearances are merely another aspect that evokes the time period. The technical aspects of the film transport you back to the period but also the costumes and the art direction as well.

Schwartz: What’s funny about the first-time actors versus the more seasoned actors is that, in some ways, I think that that role for Wiley is closer to what he’s really like than any other film I’ve seen him in. [Laughs.] He’s so incredibly intelligent with computers. His day‑to‑day interactions with computers are much more complex than mine. Even watching him on set and seeing how excited he was to just be helping behind the scenes… In that sense, Andrew would tap into Wiley’s inner character.

Marlow: At the screening in Austin, Wiley seemed very open about expressing how comfortable it was to be in a film that’s quite close to his own personal interests.

Schwartz: Yes, that completely caught me off guard on set. And it was great. Although I have to admit that while Shelly’s different from me, everyone that Andrew picked for the film was creative and intelligent and that, for me, was like a dreamscape of people who I would want to spend time with in any capacity, playing any character. Maybe that’s what he was looking for in first-time actors. People who are able to engage and connect. I don’t know if it’s a search for knowledge or creative energy and I don’t know if I would be that aggressive as to characterize myself as one of those people but I definitely felt like it was a weird environment where I just wanted to spend time with all those people. Where I could just talk about the future of artificial intelligence and humankind.

Marlow: This could’ve presumably been perceived as a leap into some very un‑commercial territory (shooting on an older camera in black and white, for instance). Evoking this period in a semi‑improvisational way could suggest career suicide on some level. [Laughs.] But the results point to a different outcome altogether. I could—based on what you were just saying—almost imagine an annual computer chess convention where everyone comes dressed for the part. It just seemed like such a great group of people with a familial atmosphere evoking a particular era. Maybe it’s something I can particularly relate to because I used to go to things like that when I was much younger. That odd period when the seemingly impossible was finally becoming possible.

Schwartz: That’s something that we can all tap into. I do think Andrew’s genuinely surprised that other people get it on some level.

Marlow: Are you interested in acting further? Has this piqued your interest in appearing in other things or was this a case of, ‘Well, I did that. Once is enough?’

Schwartz: It’s funny. This experience gave me this profound appreciation of schooled actors or practiced actors because it was hard and stressful and oddly exhausting on so many levels. It’s not that I want to say that I’m not an actor but I really appreciate the art of it and I think art takes time. I don’t think I could call myself an actor or say that I’m going to go out and do auditions or that that’s my future but, on the other hand, I would love to have another experience like this. It was amazing and I would definitely do something else. If someone knew that they wanted me to do something then I’m up for any challenge. But I’m not moving to Los Angeles to go to casting.

Marlow: Right, whereas someone like… You’ve worked with Jonny Mars in the past. He was almost ubiquitous at South by Southwest this year. Austin seems like a community that really allows people to not be pigeonholed into one thing. Because Jonny’s a director but he also acts in a number of films as well. And correct me if I’m wrong but you’re involved in music as well?

Schwartz: I am. I drum in a punk band.

Marlow: That’s Austin for you. More bands per capita than anywhere in the world.

Schwartz: It’s like you have to do that to live here.

Marlow: If you’re going to live in Austin, you have to be in a band. You just have to.

Schwartz: I don’t tell people I do film. That’s my secret life.

Marlow: I guess I’m trying to get at something particular to Austin and a handful of other cities. People are exposed to a diversity of possibilities. It has a very supportive filmmaking communit