The following is the sixth in a series of on-set reports by producer Jeremiah Kipp on God’s Land, a feature film written and directed by Preston Miller. God’s Land will be viewable online exclusively at Fandor this weekend, Friday, October 27th – to Sunday, October 29th, Miller’s first feature, Jones is currently available on Fandor. The entries are reposted here with the kind permission of The House Next Door (who are re-posting the odd numbered entries of the production diary).

Entry 6 begins with an 8 year old child punching Jeremiah Kipp as hard as he can. No, he’s not moonlighting on a prospective Funny or Die “Fight Club with Kids” parody. He’s helping a child actor channel his inner anger for a scene that demands a big performance by a small boy. A great producer is almost always busy on set doing things no one knew needing doing, in this case getting his palms bruised in the name of cinema. Entry #6 brings great details and many easily gleaned lessons about working with young actors. – Paul Meekin, Keyframe

Day Seven & Eight

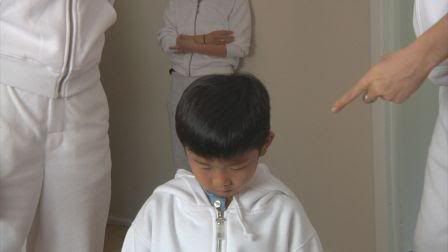

The kid is standing there punching my hand over and over again, monitoring his breath. Matthew Chiu, age eight, who has never acted in a feature film before, is working himself up for a scene where he has to attack another child actor, Brandon Suen (who plays the role of “Jesus,” the spoiled son of the cult leader—his sister Caitlyn plays “Buddha”). He has to endure a scene where he is nearly tied up to a tree and humiliated by bullies, then in a burst of rage lashes out against his oppressors. He has to knock Brandon to the ground and assault him, slapping him in the face, saying, “I’m not bad! I’m good! I’m good!” It would be a trying scene for any actor, and Matthew is just a boy. So there we are, with this child actor punching the palm of my hand over and over again, doing deep breathing exercises, in order to prepare for this scene and find the necessary level of exhaustion, frustration and energy to get through the scene.

It’s not easy for him, because he’s used to Preston’s laid-back rhythm of filmmaking. But he’s also used to me stepping in and saying, in an authoritative way, that it’s “go time” and that he has to bring it, and I won’t let him go out there in front of the camera unless he’s ready to bring his war face. Matthew, who’s an old soul, understands—he commits to the rigors of punching my hand over and over again, and breathing, and putting himself into a state of mind uncommon to him. He’s used to being a friendly, affable, quiet and introspective kid, so it’s a real struggle to find that inner anger. But he gets there, not because he wants to—he frankly does not—but he knows he has to for the movie, and he’s committed.

The scene is borderline surreal, with three little kids in their white cowboy outfits—and two of them wearing blue and yellow towels as capes to play Batman and Robin. When it gets to the fight scene, I feel like Matthew is Gary Cooper and Brandon is Lee Van Cleef.

So there we are in this interrogation scene, and you hear actors all the time speak about how difficult certain roles are, how they find it hard to shake off the emotional impact of playing a scene that is traumatic—usually, I find this to be a little ridiculous. The process of acting allows you to feel so many things, an entire rainbow of emotions, and the effect is cathartic—it brings you to life, which is the very opposite of a deadening experience. Certainly, Matthew is alive during this interrogation scene, and between takes he’s himself again, relaxed and cordial, but in the moment he finds it unnerving, and for the first time he asks Preston how many takes we’re doing on this scene because it’s so emotionally disturbing. Afterward, we give him many high-fives for his bravery and he looks like he has been climbing Mt. Everest. At the end of the day, it’s just play-acting, not psychodrama—and Matthew, while committed, isn’t a method actor and easily slides back into his relaxed, easy-going mannerisms.

***

We’re over the halfway point now, which helps with morale, and a few of our major supporting actors have been shot out of the movie entirely. Preston seems relieved, since it means less people to have to schedule over the summer. We should be wrapped in July, but scheduling a no-budget movie involving nearly 30 speaking roles and a dozen principal actors is a never-ending nightmare. Preston has been shooting this movie on weekends and as we make our way into the summer months it’s vacation time and many New York independent films are going into production, which limits the availability of several cast members. As it stands, Preston is juggling the time of professional working actors who have other paid gigs lining up and non-actors who don’t understand the seriousness of calling off a shooting date at the last minute. I’m amazed the man doesn’t have gray hairs as he works the phone, politely trying to work out with at least a dozen people every week whether they can do it. He finds this to be single-handedly the most difficult, painful part of the process; it’s the drudgery of looking at a calendar and negotiating time, which is the managerial part of filmmaking—a million miles removed from the joyful art of playing in front of a camera, telling stories, drinking a couple of beers after the wrap and slapping each other on the back.