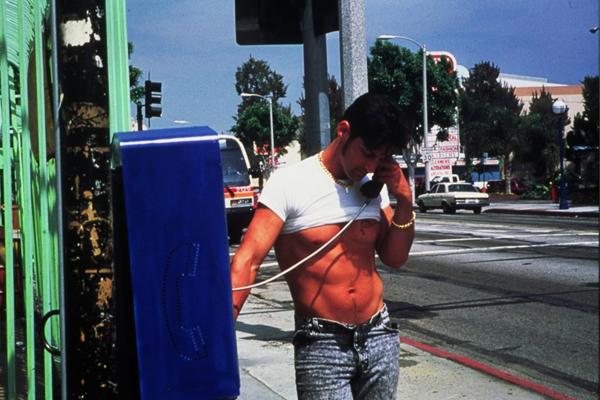

Bruce LaBruce is known as a prolific provocateur of underground queer cinema. The Canadian filmmaker’s most famous achievements–Hustler White or The Raspberry Reich–can be described as art-porn. However, LaBruce always liked to mix conventions of pornography with other genres, like agitprop or romantic comedy. It is the latter that comes to mind while watching his 2013 feature, Gerontophilia, which plays this week at the Frameline Film Festival. Essentially, it’s a love story, but with a subversive touch–the protagonist is a young man who is sexually attracted to elderly people. With this project LaBruce has abandoned art-porn for more soft-erotic visuals, trying to blend mainstream appeal with queer sensibility. During our conversation at the Venice Film Festival in 2013, he discussed this change in his approach, explained why Canada is a new evil empire and tackled the idea of revolution.

Keyframe: Why did you decide to make a film about a relationship between a younger man attracted to an elderly man?

Bruce LaBruce: This is something which appeared in my previous work. I made a film called Hustler White about male prostitutes and their relationships with older men. However, it was a story about people who weren’t necessarily gay or never identified themselves as gay, but were nevertheless involved in these interesting relationships, which sometimes had an emotional dimension, master-apprentice dynamics or just a sexual pleasure—’justified’ by receiving payment. I thought to myself: what if you took away that last part of equation and show a young man, an adult, is sexually attracted to old people, but it’s not about money—it’s a fetish. I met a couple of young men who told me their first relationship was actually with a much older man. It’s not uncommon, it goes back to ancient Greece.

Keyframe: Do you mean the Greek notion of an educational and sexual relationship?

LaBruce: Exactly.

Keyframe: Many of your previous films can be classified as art-porn, because you experimented with aesthetics of pornography. Gerontophilia, however, is more soft-erotic in its sensibility. Why the change? Is it the subject that required more subtlety in your opinion?

LaBruce: I wanted to try a different way of making a film, with a different process, intended audience and genre. I never made art-porn films because I wanted to be a pornographer. I was interested in conventions of pornography, in pornography as a genre. Narrative conventions of porn, the way you shoot porn are very specific. Then I was interested in mixing genres, like mixing porn with romantic comedy or political agitprop movie. This time I wanted to make a kind of romantic comedy, work within more mainstream narrative conventions, get the financing from mainstream institutions, work with bigger crew and budget. In a way, I tried to be experimental and even shocking—you can shock someone….

Keyframe: …by not shocking?

LaBruce: Yes, because I am perceived as a scandalist, on account of the films I made. Which is fine, I don’t have a problem with that.

Keyframe: What kind of audience did you have in mind while making Gerontophilia?

LaBruce: I started out making films in more of a punk context. They were screened in underground venues, galleries or even bars. I didn’t really think about it, it was a form of self-expression, the world I lived in. I used a lot of my friends in the movies and displayed explicit sexuality. With this film I thought it’d be interesting to take a theme which is still taboo, controversial, but make a film for a wider audience. The film has a fourteen rating [meaning persons over fourteen years of age need no adult accompaniment to view the film], so that’s certainly new to me.

Keyframe: But you could say there’s a political side to Gerontophilia too.

LaBruce: I like to think it’s gently subversive, because romantic comedy conventions are used in ironic way—the old man is an object of desire, he’s being fetishized with close-ups, which turns the genre upside down. Many of the elements of the film are meant to go against people expectations—like young man interested in old man and not the other way around. It’s subtle, but earlier today Italian journalist told me he had taken a couple of friends to see the film and they thought it was disgusting. You can try and make more mainstream and subtle film, but still there are people who will be outraged.

Keyframe: Do you believe modern society will finally accept these relationships? Not only homosexual, but also with a huge age difference?

LaBruce: It’s not like I want to make a point about some ‘big issue.’ It’s more about my characters being open to that kind of experience, and about people refraining from judgment. In that sense it becomes a metaphor for a lot of things—being gay, having fetish or just being different. That’s what the younger [man] comes to terms with—he doesn’t understand why he’s attracted to [very] old men, he can’t articulate it. His girlfriend Desiree plays an important part in the film, because she is able to articulate it. Quite often I show the female characters who are revolutionary, intellectual feminists, explaining what’s actually going on. And Desiree tells him that what he’s doing is revolutionary.

Keyframe: Love is ageless?

LaBruce: Absolutely. It’s something you can’t define. Casting the movie was very challenging, because we were looking for an eighteen-year-old and an eighty-three-year-old who would be able to go on camera with a believable chemistry. That only worked because the two actors developed strong friendship and bond off-screen. They appreciated each other. Young Pier-Gabriel Lajoie learned a lot from Walter Borden. In many movies sexuality of elderly people is portrayed as grotesque, laughable, ridiculous. You also have this idea of older women, cougars, preying on young men. I tried to do something exactly opposite, sort of turn these notions around.

Keyframe: Gerontophilia is your first film shot in Canada for years. But there’s also another Canadian connection—a book by Alice Munro, which appears in the film. I think she’d like your film.

LaBruce: Thank you, that’s a big compliment. Alice Munro actually lived fifty-to-seventy kilometers from where I was born. She wrote about average people, who find themselves in emotionally interesting situations, dealing with common problems, like divorce or infidelity. Another person I name-check in the movie is Margaret Laurence. She wrote this amazing book The Just of God, which was made into a movie Rachel, Rachel by Paul Newman. It’s one of my favorite films. I just love American movies from late sixties and seventies, particularly character studies of average people in extraordinary circumstances, for example two characters who are unlikely to find each other, but they form a bond.

Keyframe: Would you like to adapt one of Munro’s short stories someday?

LaBruce: Absolutely, that’s a good idea!

Keyframe: And what about coming back to Canada? Was it your decision?

LaBruce: I haven’t made a movie in Canada since 1994. I made two in Los Angeles, two in Berlin, I shot one in London. It was kind of self-imposed exile, even though I maintained base in Toronto. I was making these crazy, off-the-wall, often sexually explicit movies and I just couldn’t get them financed in Canada. In fact, I was routinely censored. Even the police would come to my lab and confiscate the negatives in the early nineties. And the customs would always seize my films at the border, when I tried to mail them. I could get financing and freedom of expression in Berlin, so it was the obvious place for me to go.

Keyframe: You were talking about a female character. I think there is a satirical edge to her portrayal, especially when the young man points out that Naomi Klein’s No Logo became a logo itself. Maybe one of the subjects or subtexts of the film is the meaning of being revolutionary—do you simply read Naomi Klein or do you actually do something against conventions?

LaBruce: You’re right, that’s a theme permeating all my movies—people who don’t practice what they preach and also the oppressed becoming the oppressor. Like I said, the female characters in my movies are often intellectual feminists, but there’s always a bit of satire there. They are my intellectual point of identification, so in a way I’m making fun of myself, because I do the same thing. No one can live their politics perfectly, there’s always something in the way that makes you morally corrupt or at least ambiguous. So these very idealistic characters, who are making loud pronouncements, are always gonna end up contradicting themselves. Because I contradict myself.

Keyframe: The Canadians are not renowned for revolutionary fervor. I remember seeing a satirical cartoon depicting Canadian protest, in which the protesters were holding signs ‘I really disagree.’

LaBruce: Yes, ‘I really think I disagree!’ But I think it’s a cliché that doesn’t apply anymore. I contribute to Vice Magazine sometimes and recently I’ve written about Canada as a new evil empire, imperialistic-minded and ruthless about exploitation of oil worldwide, with really bad environmental policies and very right-wing government for the past six years. So the illusion of ‘nice Canadian’ became a cliché. Actually, in Quebec, where I shot Gerontophilia, there was a separatist party in the sixties, demanding independence for Quebec. They kidnapped and killed people, so Canada has its own terrorists.

Keyframe: What’s your approach towards the idea of revolution?

LaBruce: Well, I’m married to a Cuban….

Keyframe: That’s an interesting clash.

LaBruce: I met him, when I was making The Raspberry Reich or just after. Somebody called that film ‘subversive’ and he laughed so hard. He used to mock me: ‘Brucito subversivo!’ Because I grew up in this very affluent country which never had much political strive, and he went through Cuban revolution, he had to pledge allegiance to Che Guevara every morning in public school, he was forced to learn how to use a machete and so on. He lived through a real revolution, and he still feels very ambivalent about it. There were parts he thinks were idealistic, but he also remembers parts that were rather imperialistic.

Keyframe: That reminds me of Milos Forman’s reaction in Cannes, when Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and others interrupted the festival in 1968 to express support for protesting students and put a red flag up. Forman was stunned: ‘What are you doing? We are trying to get this flag down in Czechoslovakia and you’re putting it up?’

LaBruce: Yes, that’s also the case of Maoists in Western Europe and revolutionaries in Raspberry Reich. But there are also quiet, personal revolutions. That’s what Desiree explains to the young man: in a way, you’re a revolutionary, because you’re going against nature, which dictates choosing young sexual partner, and you’re going against ideas of beauty dictated by culture. He’s not even doing this consciously, but going with his instincts. He’s also a revolutionary.

Keyframe: Are you scared of getting old?

LaBruce: I think it concerns everybody, regardless of their age. Especially nowadays, in a very difficult demographic and economic situation. And of course, you become more invisible socially, your sexuality becomes something ‘shameful’. I think it concerns homosexuals even more—when they get old and live in caring facilities, they often have to go back to the closet, hide their sexual orientation. Even now it is not accepted for them to exploit their sexuality. So I think about it, also in terms of impermanence of the flesh. But this impermanence can also be attractive—in a sense that it’s a body with a last chance to have fun, experience pleasure and joy.