[Editor’s note: As the Berlinale is now in full swing, we offer this ‘Cinetopographical Berlin,’ one in our series of Cities on Screen lists.]

Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have us locked up hopelessly. Then came the film and burst this prison world asunder.

—Walter Benjamin

The topographical Berlin, which one can journey to by train or plane, was born in the 12th century. The celluloid Berlin, which one also buys a ticket for but takes a different kind of trip to, materialized much later, towards the end of the 19th century. The silver screen immediately became a site of living memory for the city, as well as a means by which to project into future.

The “birth” of the celluloid Berlin took place on a rooftop above the Schönhauser Allee, when the inventors of German cinema, the Skladanowski brothers, captured Berlin’s skyline. Only a few of those frames remain, ghostly and fading. Provoked by these images, we will explore some of the best examples of Berlin on film.

The focus here is on the dramatic use of the real Berlin as opposed to the fabricated, though often brilliant, Berlins of the film studios, constructed in Germany and elsewhere (this explains the absence of Lang or Murnau on our list, for example). The allure of Berlin films derives from their connection with well-known places that have a firm hold on the public imagination. Seeing these urban spaces and architecture through the camera lens, altered so as to create unique filmic spaces with totally disparate psychological effects, demonstrates the transformative effects of cinema.

Berlin tells a Hollywood story of its own; one of rise and fall (and rise again). One has only to consider the history of the city: from a fishing town to a European metropolis; from a sin city, film capital and the intellectual heart of Europe to a melting pot of ideology and hatred, anxiety and fear. During World War II it was a battlefield, leaving a landscape of devastation. Reemerging from the ashes, Berlin became an island before redeeming itself of the Cold War divide by tearing down the most notorious wall in modern history. German films have told the story in different ways.

The following selections are presented in chronological order, to give the reader a clearer sense of the ways in which the real Berlin and the celluloid have complemented one another decade by decade. We view Berlin as a place of ideas, will, decadence, defeat and loneliness, which means stands in isolation from many other key European cities of cinema, such as Paris and Rome. Our focus is on the city as a living organ, its monuments and neighborhoods, rather than its inhabitants and how they fit into this colossal scenery. We believe every urban filmmaker is a descendant of Eugène Atget. Atget’s search through haunted streets of the city, evacuated of any human presence and revealing a soul of its own, has been a model of ours.

Our respective backgrounds play a decisive role in how we see a cinematic city, in this case, Berlin: Ehsan is an architect and studies urban design and film history. Ekkehard is a musician, silent film composer/accompanist and photographer. Ekkehard is a Berliner whereas Ehsan is a visitor to the city. Ehsan has made a documentary about the city’s film and architecture in the expressionist era and Ekkehard has recorded a jazz album around Berlin and its legendary districts and moods.

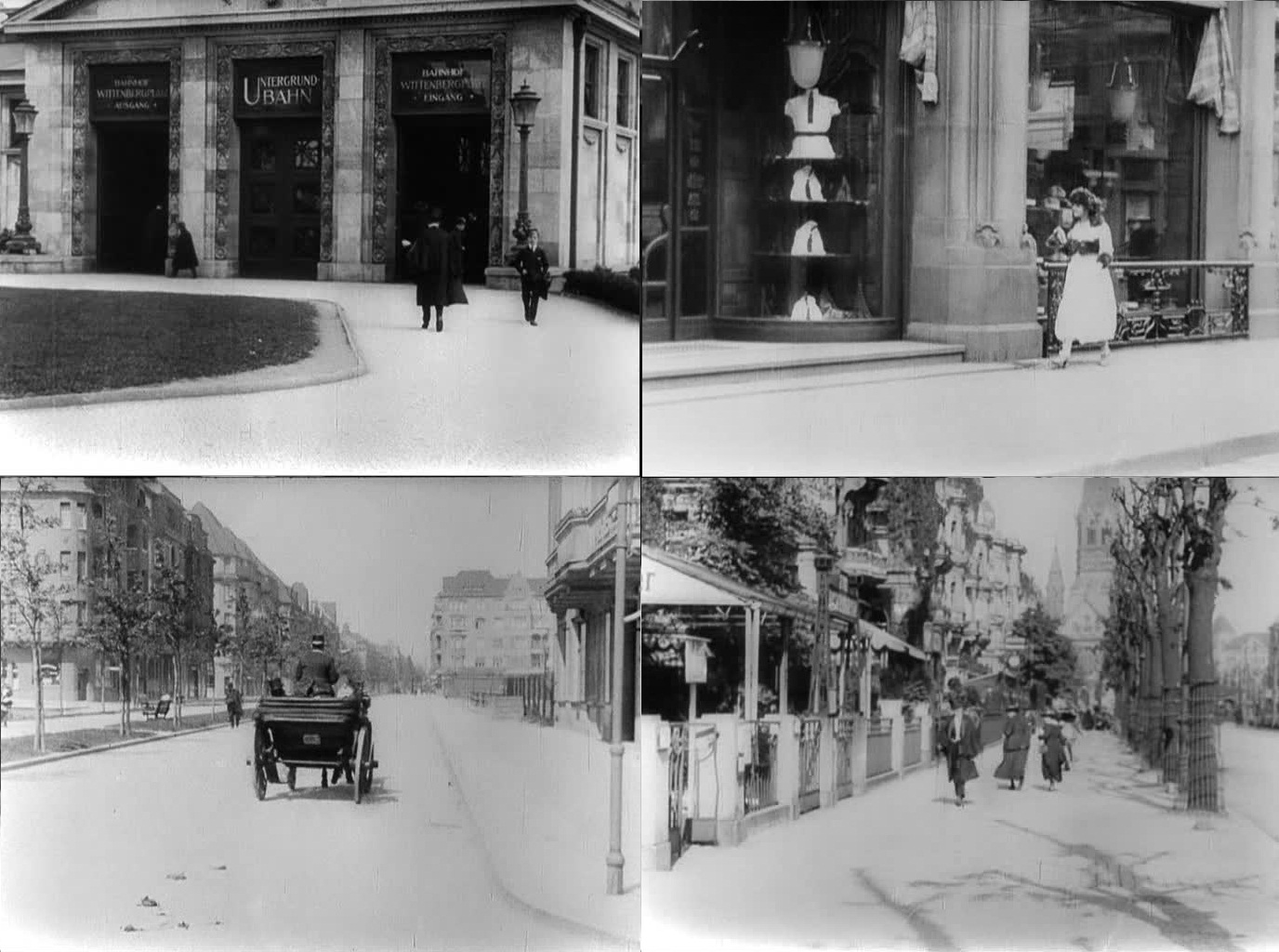

I Don’t Want to Be a Man [Ich Möchte Kein Mann Sein] (Germany, 1918, Ernst Lubitsch)

In the last days of World War One, Berlin was a city of excessive pleasures, dandies, quiet streets and busy nightclubs. That was before it went low key and expressionistic. The Berliner Ernst Lubitsch, who grew up on Schönhauser Allee in Prenzlauer Berg (where the celluloid Berlin was born), made this charming comedy about the battle of the sexes and gender swapping amidst the city’s heady nightlife. Sandwiched between progressive scenes of women dressing as men and same-sex kissing in public, there are authentic shots of Berlin. In an amusing scene in the U-bahn we can glimpse the Art Nouveau entrance of Wittenbergplatz Station ,which at that time was sixteen years old.

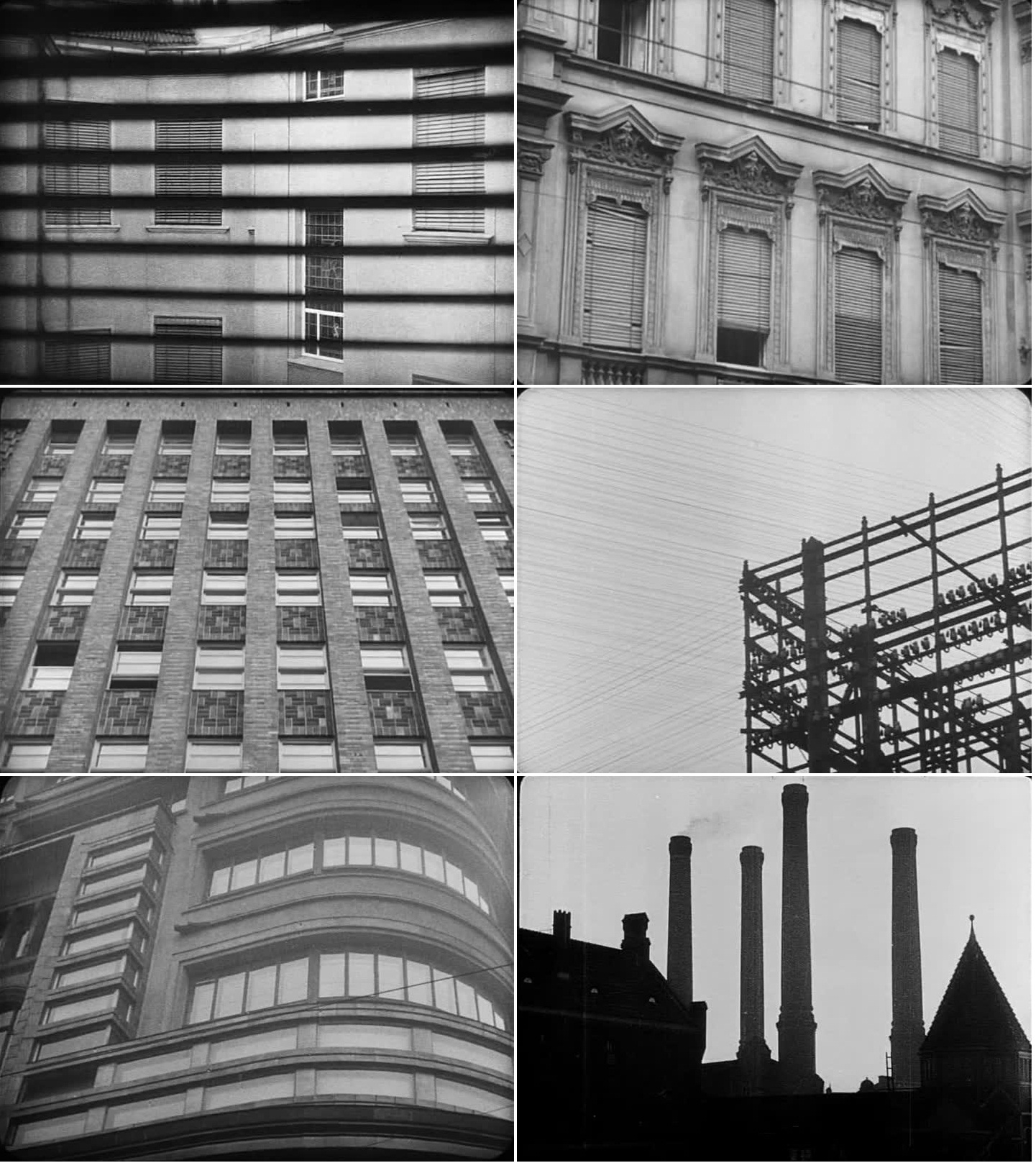

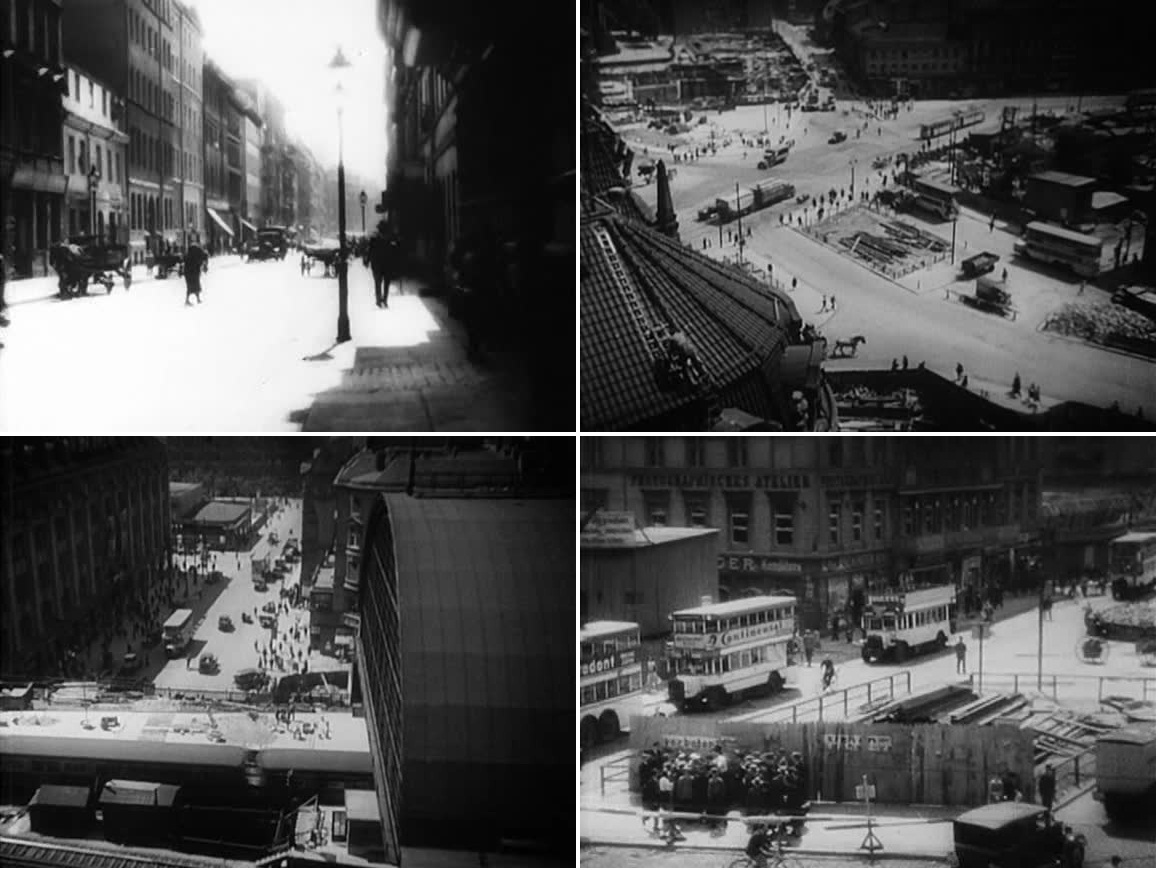

Berlin: Symphony of a Great City [Berlin – Symphonie Einer Grosstadt] (Germany, 1927, Walter Ruttmann)

This quintessential Berlin film is comprised of various verite fragments sewn together in a Soviet montage style, to portray a day in the life of the city. Here, Berlin is a concept; a dispositif of ceaseless dynamism, in which human activity becomes mere choreography—a “melody of pictures” as producer Carl Mayer described it. Though the starting point of the film is the reality of Berlin as documented by Karl Freund’s candid camera, through rhythmic editing strategies and matching on actions, the city becomes a grand machine of organized movement and energy. It is a sight that is thrilling to a spectator but which appears somewhat intolerable to be a part of.

There are countless images of famous Berlin locations, such as Anhalter Bahnhof in Kreuzberg at the very beginning, when the heavily steaming morning train arrives into the metropolitan station; the area around Potsdamer Platz at noon; the Tiergarten and Unter den Linden in Mitte in the afternoon; plus, during the nocturnal finale, the explosion of fireworks above the Funkturm in Charlottenburg.

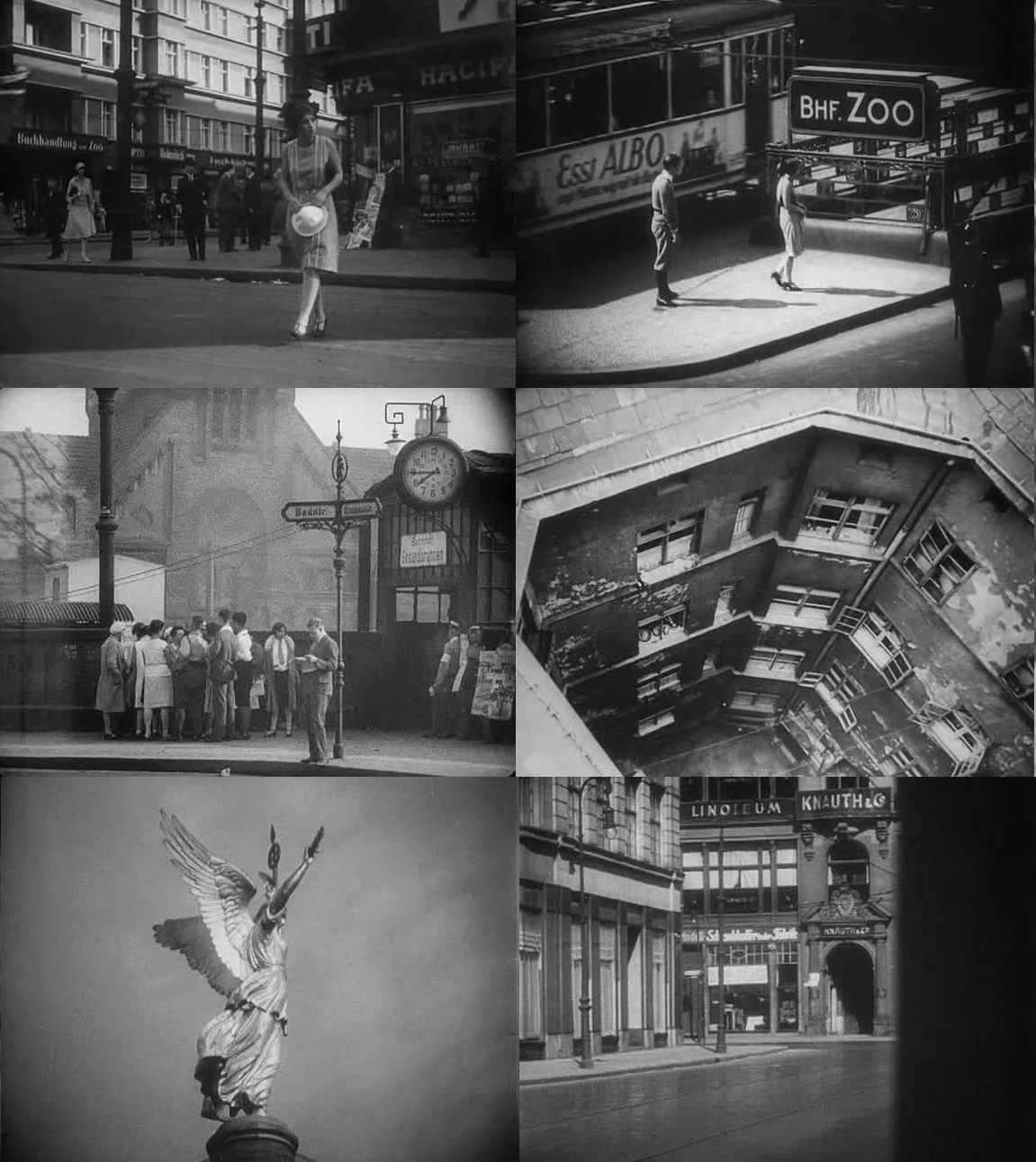

People on Sunday [Menschen am Sonntag] (Germany, 1929, Robert Siodmak/Edgar G. Ulmer)

This semi-documentary made between the wars provided not only a ladder to stardom for its legendary production team, leaving a lasting mark on the life and career of anyone who was involved, but also turned into something a cinematic model for the city films that followed, especially those of the French New Wave.

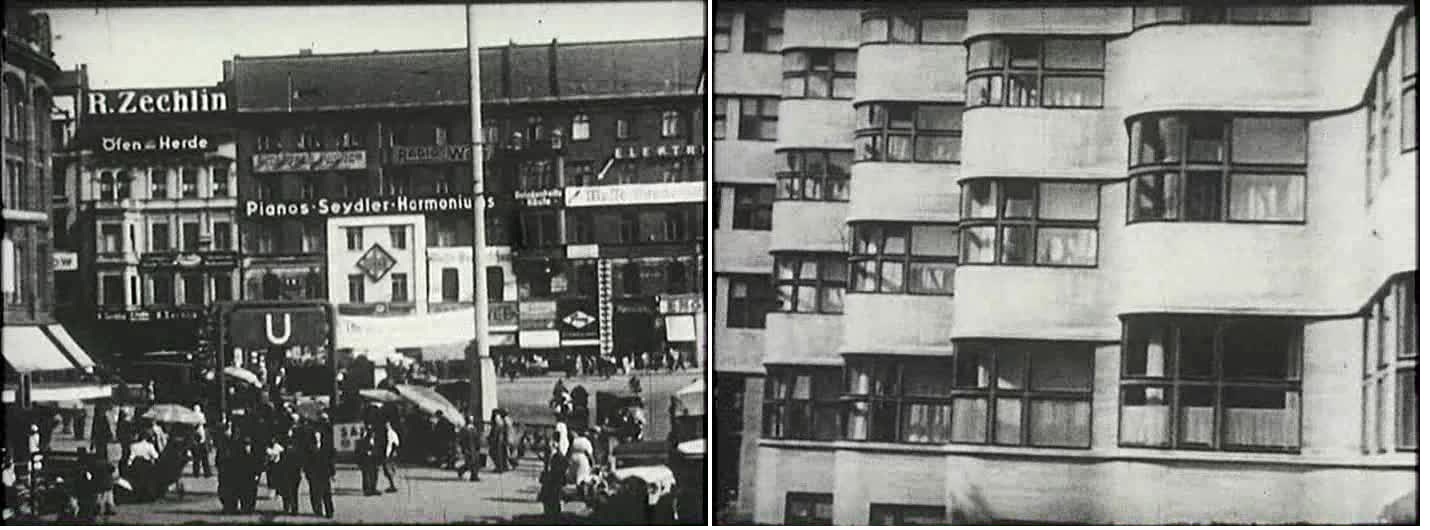

Shot gracefully by Eugen Schüfftan and acted by non-professionals, it’s a poetic account of the lives of four youngsters spending a Sunday afternoon on the banks of the Nikolassee in the southwest area of the city in summertime. They relax on the small beach before they have to return to working life on the following Monday. The film’s unsurpassable ‘light’ and youthfully exuberant mood creates an impressionistic joie de vivre which might have influenced Jean Renoir’s Partie de champagne. It includes vivid shots of the crowded area around Zoologischer Garten, views of the Havel and Spree rivers, the S-Bahn vigorously rushing to the Wannsee, and street scenes at noon at Hausvogteiplatz in Mitte and Tiergarten.

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Germany, 1931, Piel Jutzi)

Based upon Alfred Döblin’s monumental 1929 novel (later filmed in its entirety by Rainer Werner Fassbinder), this film delivers some of the most authentic street images of Old Berlin, especially the area around Alexanderplatz itself. Set in the world of crooks and pimps, the film begins with Biberkopf being released from a prison in Tegel, north Berlin, and heading to the city. This allows for a series of wonderful shots of the city in motion. We can also find various impressive shots of the Berlin courtyards, known as Mietskasernen.

Kuhle Wampe (Germany, 1932, Slatan Dudow)

This explicitly Marxist classic of the Weimar Republic written by Bertolt Brecht and accompanied by an overwhelmingly powerful and aggressive musical score by Hanns Eisler, caused a scandal upon its release. It depicts the city as the collective force of its working class inhabitants and follows the destinies of starving, jobless Berliners who begin to organize themselves and demonstrate their class solidarity.

The film opens with various sights of industrial Berlin and its working class neighborhoods before the city and its problems are elaborated more predominantly in conversations among the ordinary people. Nevertheless, there are many great images of Berlin, most significantly the Müggelsee, where the workers spend their weekend. If you’re looking for a connection between Brecht and the cinema of Godard, there are many examples to be found here, not least the man who reads aloud the story of Mata Hari in all its lustful detail, intercut with various shots of basic commodities and their seven digit price tags during the hyperinflation.

Hitlerjunge Quex (Germany, 1933, Hans Steinhoff) + Berlin Remains Berlin [Berlin bleibt Berlin] (Germany, 1935, Franz Fiedler)

During the Third Reich, Berlin became a playground for political power games. Hitlerjunge is one of the first openly fascist films in which shabby housing is contrasted with the order and vigor of Nazi parades, outfits and flags. Set in the miserable working class milieu familiar from the old proletarian “street films” of the Weimar Republic, it uses the same stylistic devices to deliver an opposing political message. The film’s protagonist, a young boy named Quex who lives in Beusselkiez in Alt-Moabit with his poor family, enthusiastically joins the Hitler Youth.

Another fascist film from this period is the one-reel documentary Berlin remains Berlin, made two years after Hitlerjunge. The film is milder in its politics and features almost no explicit aggression. It aims to depict a lively, civilized, but nevertheless homogenous Berlin as the capital of classical arts, in a similar manner to Edwardian city actualities. The film promises a modern metropolis (featuring a brilliant tracking shot in Friedrichstraße) yet paradoxically it is devoid from any elements of “modern art” which was hated by Hitler.

Under the Bridges [Unter Den Brücken] (Germany, 1944, Helmut Käutner)

Berlin seen from the river: on the move and elusive. This poetic German L’Atalante was one of the very last films produced in war-stricken Berlin. The tender love triangle set among the boatmen of the Havel River features a lot of magnificent views (photographed by Igor Luther) of bridges, boats and bodies of water near Potsdam in southwest Berlin.

Germany, Year Zero [Deutschland im Jahre Null] (Italy/Germany, 1947, Roberto Rossellini)

“A sensation of fear…like approaching a giant conquered and cut up into pieces but still able to move and react,” wrote Rossellini’s assistant Carlo Lizzani, describing the horror of visiting Berlin in 1947, “I don’t believe Berlin can be rebuilt…the smell of corpses is everywhere. The hunger is frightening. Thousands of Berliners [will] commit suicide this coming winter, chiefly because there is absolutely no solution in sight.”

Rossellini’s bleak masterpiece about defeated, hunger-ridden Germany was originally called “Berlin.” It was only later that the director decided to borrow the title of an Edgar Morin book for the film. Shot among the devastating ruins of post-war Berlin, and depicting a starving population on its knees, earning a living from the black market and prostitution, the film follows a German boy who is indoctrinated by an unscrupulous ex-Nazi teacher with ideas about the “survival of the fittest.” The young boy poisons his father to release him from misery and finally commits suicide in the midst of the ruins.

There are many shots of post-war Berlin which are almost too painful to bear. Impoverished people are seen fighting for a piece of meat from a recently deceased animal on the Berlin streets, unaware that they are being filmed, and there are scenes shot around the bombed-out Reichstag. At the end of the film, the pieta-like pose of a young woman kneeling by the dead body of the boy, and the sharp rebars jutting into the frame, clearly evokes the composition of a religious painting in reverse. The camera then tilts up to reframe the ruins of a building over her shoulder, on the other side of the street. This depiction of Berlin at point zero is for us the most horrendous and unforgettable image of the city.

Berlin – Ecke Schönhauser (DDR, 1957, Gerhard Klein) + The Big Lift (USA, 1950, George Seaton)

This East German Blackboard Jungle, made two years after its American counterpart, adds everything that was missing in the original: audacity, fine character studies of delinquent youths, realistic violence and above all a sense of authenticity gained from location shooting. The story of a gang of young Berliners vandalizing what is left of the city becomes an excuse for recording areas such as Alexanderplatz, Gesundbrunnen, Zoologischer Garten and Pratergarten in the Kastanienallee, where unexploded ordnance are buried under fast growing construction sites.

As for the practicalities of life in post-war Berlin, there is The Big Lift, starring Montgomery Clift, which focuses on Operation Vittles, undertaken by the U.S. Air Force to supply tons of food and clothing to the starving population of West Berlin during the Soviet blockade of 1949. Shot less than a year after the operation, the film featured authentic newsreel footage of the starved city during the time when the tension between East and West began to rise.

One, Two, Three (USA, 1961, Billy Wilder) + Look at this City! [Schaut auf diese Stadt] (DDR, 1962, Karl Gass)

This crazy, high-speed farce starring an explosive James Cagney oscillates between East and West. It was filmed by former Berliner Billy Wilder in August 1961 around the time that the Berlin wall was being erected by the German Democratic Republic to “protect” the eastern side from the invasion of capitalism.

Almost the same story is told, though in a didactic documentary style, in Karl Gass’s propagandistic provocation which justifies building the Wall. The voiceover commenting on the images of West Berlin is heard saying, “pictures and sounds from Washington, London or Paris? No, this is coming from a German city.” Later on, the opening song of the legendary VOA jazz show, Take the “A” Train, accompanies the scenes of absolute chaos” in West Berlin. On the other hand, classical music is used to show the total accord of the eastern side, more or less in the same manner as Berlin Remains Berlin from 1935.

The East German film continues to argue that “street names sometimes tell a story,” only to show various streets in West Berlin named after American generals. The same voice is heard again: “Just when this shattered city, freed from fascism and saved from starvation, set off on the road to democracy with a new lease on life, the Western powers sent in troops. . . Chicago once stood for decadence. Today, West Berlin does.”

The Legend of Paul and Paula [Die Legende von Paul und Paula] (DDR, 1972, Heiner Carow) + The Third Generation [Die Dritte Generation] (BRD, 1979, Rainer Werner Fassbinder)

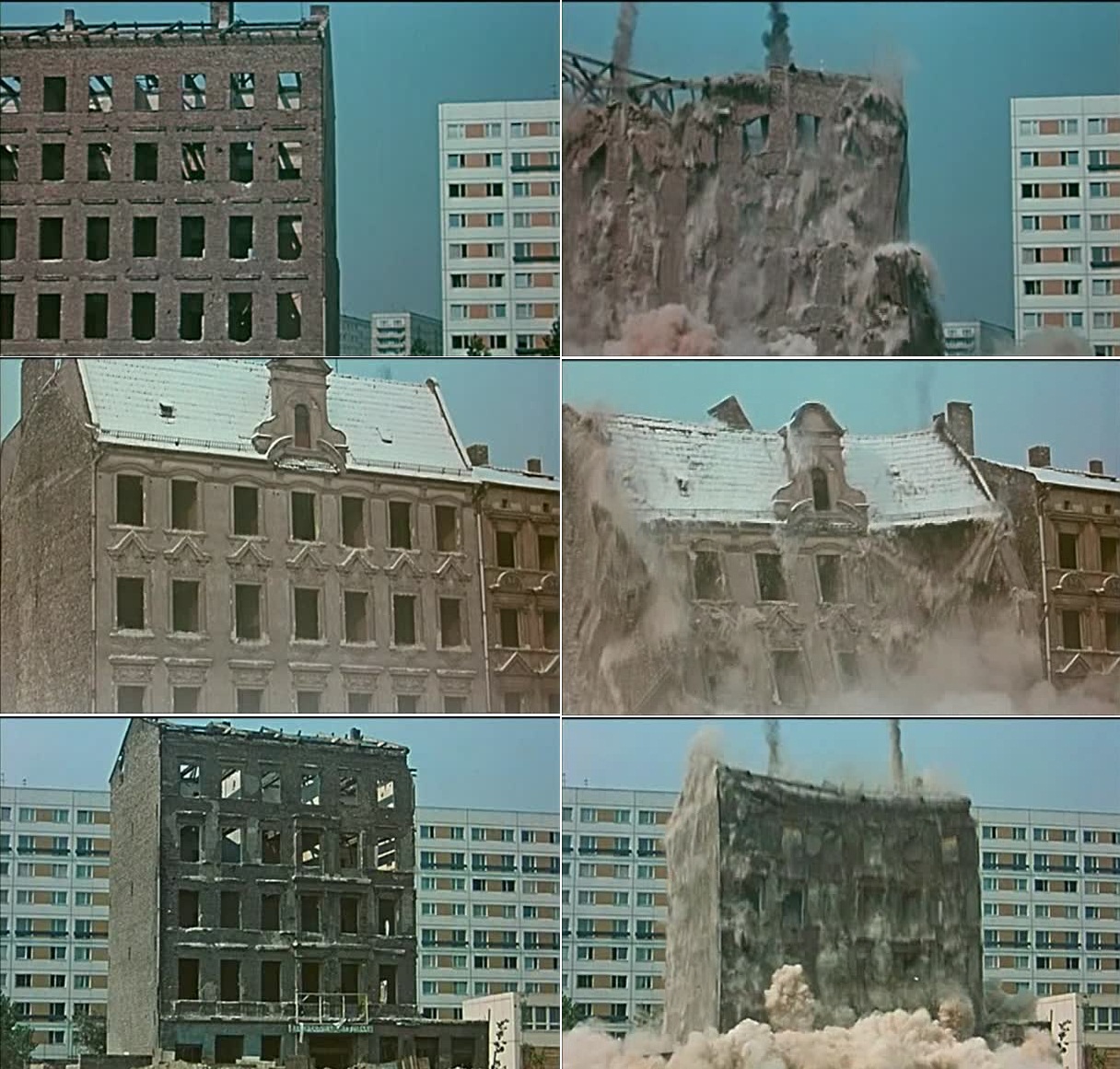

Known as the most commercially successful DEFA production of all time, and seen by almost one-fourth of the population of East Germany alone, this love story perfectly expresses a joyous ‘living mood’ of the early seventies, when a certain freedom seemed to be possible for a romantic couple even in an outwardly totalitarian system.

Enriched by many famous locations in East Berlin, like the monotonous Plattenbau inSingerstraße 51 (Friedrichshain) and especially the Rummelsburg Lake in Lichtenberg–where a section is today named after the film’s two protagonists–the film, as Sebastian Heiduschke argues, turns buildings and architecture into political subtexts. (As the love story is followed throughout the years, old buildings are demolished and new residential blocks are erected, suggesting that Berlin is changing.)

In the 1970s, on the other side of the Wall, the Berlin of Fassbinder is a bleak hideout for anarchists and heroin addicts. The city is barely shown, but its melancholic presence in the background is felt on the absurd action played out indoors. The walled Berlin has become in Thomas Elsaesser’s words, “an aquarium, constant movement behind glass, transparent but enclosed, claustrophobic and untouchable.” As the films opens, a striking experimental soundtrack plays over a view of the Gedächtniskirche shot from tower block window. The landmark is slowly obscured as the camera zooms back to reveal an interior furnished with an IBM computer and a TV connected to VCR playing Bresson’s The Devil, Probably. Conveying the paranoia and surveillance of the Baader Meinhof era, the film feels as contemporary as any post-9/11 film.

Wings of Desire [Der Himmel über Berlin] (BRD, 1987, Wim Wenders)

Wenders’s Rilke-inspired cult film explores, in Collin Chua words, “the tension between alienation from contemporary society and the quest for authenticity, immediacy and belonging, coupled with the desire for freedom and movement.”

The ravishing images of Berlin photographed here by Frenchman, Henri Alekan include the iconic shots of two angels sitting on top of the Siegessäule conversing about city and its wastelands. Peter Falk is seen in front of the Anhalter Bahnhof’s ruin and an old Curt Bois tries to find old cafes he had known in the 1920s, in the disastrous wall-cut verges of Potsdamer Platz. Other significant places featured in the film are the state Library at Potsdamer Platz, the Sony Centre, the Langenscheidt Bridge in Schöneberg and the Grand Hotel Esplanade.

Allemagne 90 Neuf Zero (France/Germany, 1991, Jean-Luc Godard)

The impressions felt by Lemmy Caution, lost after the fall of the Wall and struggling to find his way back to the West, are the subject of this celebration of the masters of Weimar cinema–as well as forming an elegy for Berlin. Watching the city segments of the film, one feels as if being carried into a no man’s land; the ruins in the background recall Rossellini’s 1947 images of Berlin. Outside the city, the sudden appearance of massive industrial machinery (comparable to the windmills in Don Quixote) is symbolic of a new destructive force, that of capitalism, now underway.

Godard shows people and places caught between eras and destined to disappear into the fog with historical developments to come. A haunting, almost phantom-like view of the Sakrower Heilandskirche, a church near Potsdam and the Glienicker Brücke which fell in no man’s land and was completely inaccessible until 1990 prompts an unusual and affecting anachronism. Access to spaces means access to history. There are also wonderful glimpses of the Tacheles–a former department store which became the ultimate cult landmark of early nineties Berlin–and the glittering capitalist neon signs of Kurfürstendamm.

Summer in Berlin [Sommer Vorm Balkon] (Germany, 2005, Andreas Dresen)

A light-hearted comedy about the lives of two young women in post-1990 Berlin, where the Wall is gone but the clash between East and West has not entirely vanished. Set in a renovated apartment block in Prenzlauer Berg, the film offers a contemporary perspective on the themes of family (common to many Berlin films discussed here), employment and gender identity. The film revives to a certain extent the elusive feeling of People on Sunday.

At one point, we see a shot of two children enjoying the view of Berlin from the rooftop of a building located not far from where the Skladanowski brothers filmed their first moving images of the city. This not only brings us full circle with regards to Berlin on film, but also suggests that the celluloid Berlin has been searching for that lost image from the earliest days of German cinema; the image of a city whose past remains overwhelmingly decisive in every move towards its future.