Along with the requisite blockbuster properties, the spring and summer months tend to bring counter-programming titles to a more discerning cinephile, particularly those who may not live in one of the nation’s greater metropolises and thus aren’t afforded the luxury of a local film festival or art house to program such fare all year long. This past summer/spring season, for example, you may have seen Jeff Nichols’ Mud, Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight, or Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine playing across town from your Man of Steels, Pacific Rims, or World War Zs. With the advent of video-on-demand and various such streaming services to augment theatrical runs, however, an even more niche subset of cinema has become a viable alternative to the multiplex. Take documentaries, which have experienced some notably beneficial exposure through such means and, in particular, one of the more popular forms of non-fiction filmmaking, the music documentary, which has flourished recently in its own modest way. What’s especially struck me about this year’s rock docs, however, is the near-universal acclaim they’ve garnered from mainstream critics while leaving much of the academically-inclined crowd content if unenthused.

Normally such a critical divide wouldn’t much move the needle on my cinematic radar; after all, I’d likely be grouped amongst the latter crowd more accurately than the former. Also, this isn’t exactly what anyone would consider a new phenomenon. But these films, now so much easier to access, have not only accumulated more reviews, but also, crucially, more opinions from a greater demographic of writers and cultural enthusiasts. In short, more fans of these bands have been able to see these films while they’re still in theaters and being discussed online or in public forums than ever before. Three of the most widely seen, well regarded documentaries of 2013—Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, A Band Called Death and Sound City, all spirited, even moving entertainments—nonetheless reiterate an interesting problem facing critics attempting to reconcile differing media. Namely, where does one draw the line between praising the subject on display and dissecting its formal presentation? Or, in other words, where does appreciation for the music end and your faculties in relation to the filmmaking begin, and is this contradictory impulse a fair critical model?

It’s a question I’ve continually returned to over the years, as my dual interest—and, indeed, professional pursuits—in both music and film criticism have dovetailed on more than one occasion. But with the production of music documentaries at an all-time high, it’s one worth reconsidering across a broader spectrum. In a piece on Nothing Can Hurt Me for Pitchfork’s recently launched blog The Pitch, my former colleague Lindsay Zoladz describes the film as “warm and melancholy as a setting sun,” serving “as an overdue but fitting epitaph for a band whose songs always felt imbued with personal pain.” And this is true. In fact, I don’t disagree with much of what Lindsay refers to as Nothing Can Hurt Me’s most “powerful” moments. But these moments, as moving as they are in context, are also facts, real-life instances, coincidences and tragedies that beset the band and which have been written about for years. Beyond this, there’s nothing of particular interest, either aesthetically or narratively, in Drew DeNicola and Olivia Mori’s retelling of Big Star’s flat-line trajectory. What we’re left with is an entertaining, inherently emotional, yet totally traditional documentary about one of the greatest bands of the last half-century.

But is this in and of itself a problem? I mean, I like this movie. I enjoyed my initial viewing and will probably watch it again somewhere down the line. And I don’t mean to single out Nothing Can Hurt Me. The same problem afflicts the aforementioned A Band Called Death, a firsthand account of the Detroit proto-punk band, and Sound City, a personal history of the famed Los Angeles recording studio, not to mention countless other documentaries about all sorts of subjects more topically important than music. But for the sake of argument, what these films are offering are, essentially, oral histories, which in their printed form are far more detailed and substantial than any ninety-minute movie could hope to be. (Imagine condensing say, Mark Yarm’s Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge, into a documentary narrative). For a kid who grew up on VH1 Behind the Music specials, and appreciated them for the very same reasons these theatrical documentaries give me pause (namely, the implication that they’re inherently cinematic ventures), it becomes even more difficult to endorse such an investment.

There seems but a few ways to bridge the divide, all admirable yet none completely satisfying. Zeroing in on one specific moment in an artist’s career, diving deep into the contextual currents which inspired such music, has proven popular lately: Ed Haynes’ Brian Eno: The Man Who Fell to Earth (2011) and Rob Johnstone’s Kraftwerk and the Electronic Revolution (2008; and both MVDvisual productions), as well as Martin Scorsese’s mid-sixties portrait of Bob Dylan, No Direction Home, are all highly detailed, lengthy documents (each around three hours) of very specific eras, though in most every other way rather standard-issue talking heads assemblages. Another approach, if one is lucky enough to have access to such material, is to prominently integrate rare or exclusive footage that even a book would have trouble visually approximating. The exemplary modern example of this method has to be The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005), for my money the most vital and certainly most memorable of the modern, traditionally-minded rock doc. Not only is director Jeff Feuerzeig offering disarmingly intimate footage of our titular cult hero, but he’s stitching together a grand dramatic narrative from this disparate, oftentimes unintelligible material (a similar example of this can be seen in Ondi Timoner’s 2004 film Dig!). And, more importantly, it plays just as well for fans as it does for novices.

Then there’s the opposite approach, which, for lack of a better term, we’ll refer to as a formalist methodology. Generally speaking, these are the accomplishments which I and other critics would champion as works of conceptual and aesthetic integrity, less concerned with narrative as historical documentation than as taxonomical record. These are far rarer: Pedro Costa’s stunning chiaroscuro portrait of Jeanne Balibar, Ne change rien (2009), is probably the best and most recent work in this vein, while D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back (1967) arguably pioneered a more vérité strain of these same techniques many decades ago. Meanwhile, AJ Schnack’s Kurt Cobain: About a Son (2006), which approaches its subject from a standpoint of similarly visual intrigue but in more essayistic terms, is less disarming but equally enticing. This less narrative driven approach can also be witnessed in differing formulations in, for example, Michael Tully’s Silver Jew (2007), which captured the former Silver Jews frontman on a spiritual excursion through the Middle East, as well as concert and tour documentaries stretching from Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil (1968) and Scorsese’s The Last Waltz (1977) to Jem’s Cohen’s Instrument (1999) and Dylan Southern and Will Lovelace’s Shut Up and Play the Hits (2012). In most of these cases, what you’re witnessing is less an archive of talking points than a meditation on the artistic plight.

At the end of the day, I’m not sure there’s a correct answer to how one exactly goes about hedging their critical appraisal of the modern music documentary—it’s certainly not an exact science and I, for one, have oftentimes gained as much knowledge from stock interviewees as I have spiritual insight from some of these films’ more abstract properties. There’s obviously an audience, no matter how small, for each of these styles. Some may succeed to varying degrees based on one’s background or creative ideology, as do many such artistic compendia. But if they inspire an unsuspecting viewer to further research any of these artists or movements, or are able to enrich anyone’s appreciation of said artists, then they have succeeded on their own individual terms and thus are difficult to raise much dispute over. What’s particularly nice nowadays is that no matter their greater functionality, these films are almost all readily available to their largest potential audience, and, depending on how one wishes to engage with such entertainment, in their most appropriate of viewing environments as well.

With that in mind, below you’ll find an unofficial list of twenty-five of the more notable music-related artifacts of the previous ten years—some short, others lengthy; some I consider impressive cinematic achievements; and others still that are just a lot of fun.

I Am Trying to Break Your Heart (2002)

Jandek on Corwood (2003)

Dig! (2004)

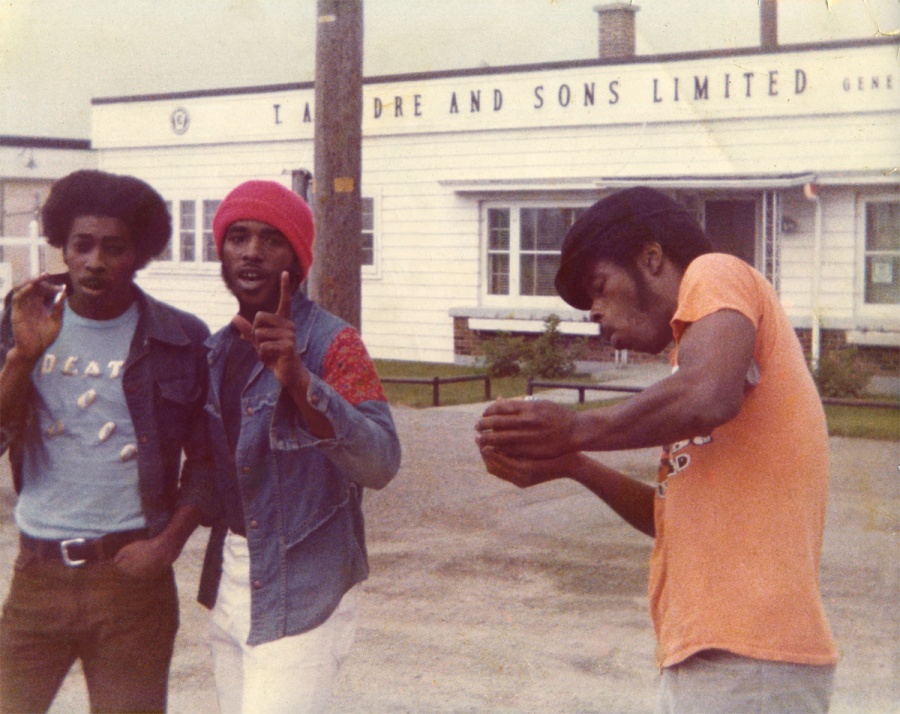

Kill Your Idols (2004)

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (2004)

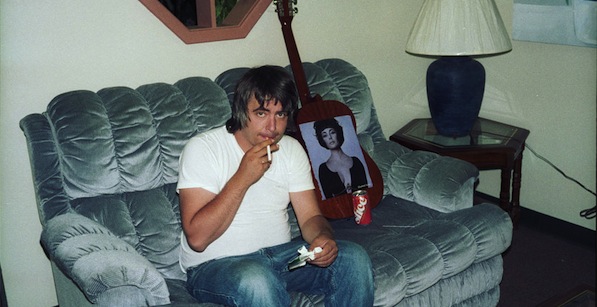

The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005)

The Fearless Freaks (2005)

We Jam Econo: The Story of the Minutemen (2005)

You’re Gonna Miss Me (2005)

American Hardcore (2006)

Kurt Cobain: About a Son (2006)

Black and White Trypps no. 3 (2007)

Silver Jew (2007)

Anvil! The Story of Anvil (2008)

Kraftwerk and the Electronic Revolution (2008)

No Direction Home (2008)

Ne change rien (2009)

Who is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everyone Talkin’ About Him)? (2010)

Better Than Something: Jay Reatard (2011)

Brian Eno: The Man Who Fell to Earth (2011)

Hit So Hard (2011)

George Harrison: Living In the Material World (2012)

Searching for Sugar Man (2012)

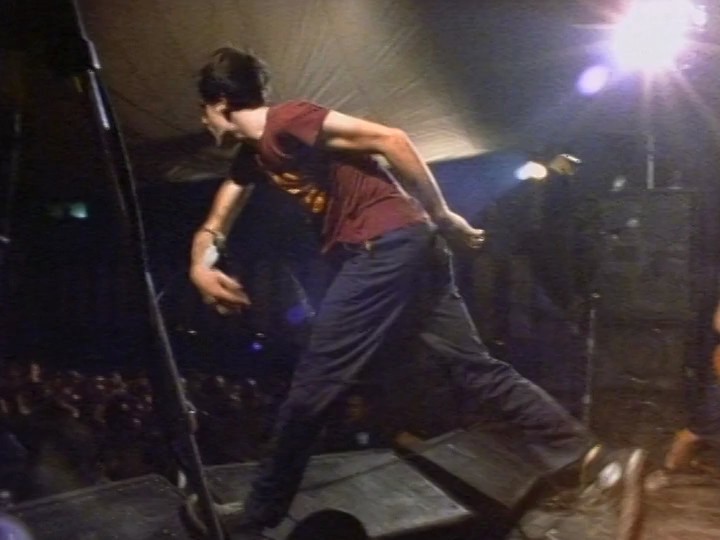

Shut Up and Play the Hits (2012)

The Source Family (2012)

Jordan Cronk is a Los Angeles-based film and music critic. In addition to Keyframe, his work has appeared in the digital and physical pages of Slant Magazine, Reverse Shot, Little White Lies, CokeMachineGlow, and Indiewire. He also tweets about film, music and unrelated things at @JordanCronk.