In the wake of the #MeToo movement, the once-revered films of renounced men can only be considered with a massive asterisk, if at all. Rather than mourning the loss of carefree viewings of the works of these questionable filmmakers or, more considerately, mourning the absence of work from actresses who were shut out, as a result, the best way to cope maybe instead to re-evaluate underappreciated works by women, people of colour, and the LGBTQ+ community. Cult films have always been a place for underrepresented sections of society to have a voice and find like-minded viewers, so the time is ripe to expand the definition of what it is to be a “cult” film.

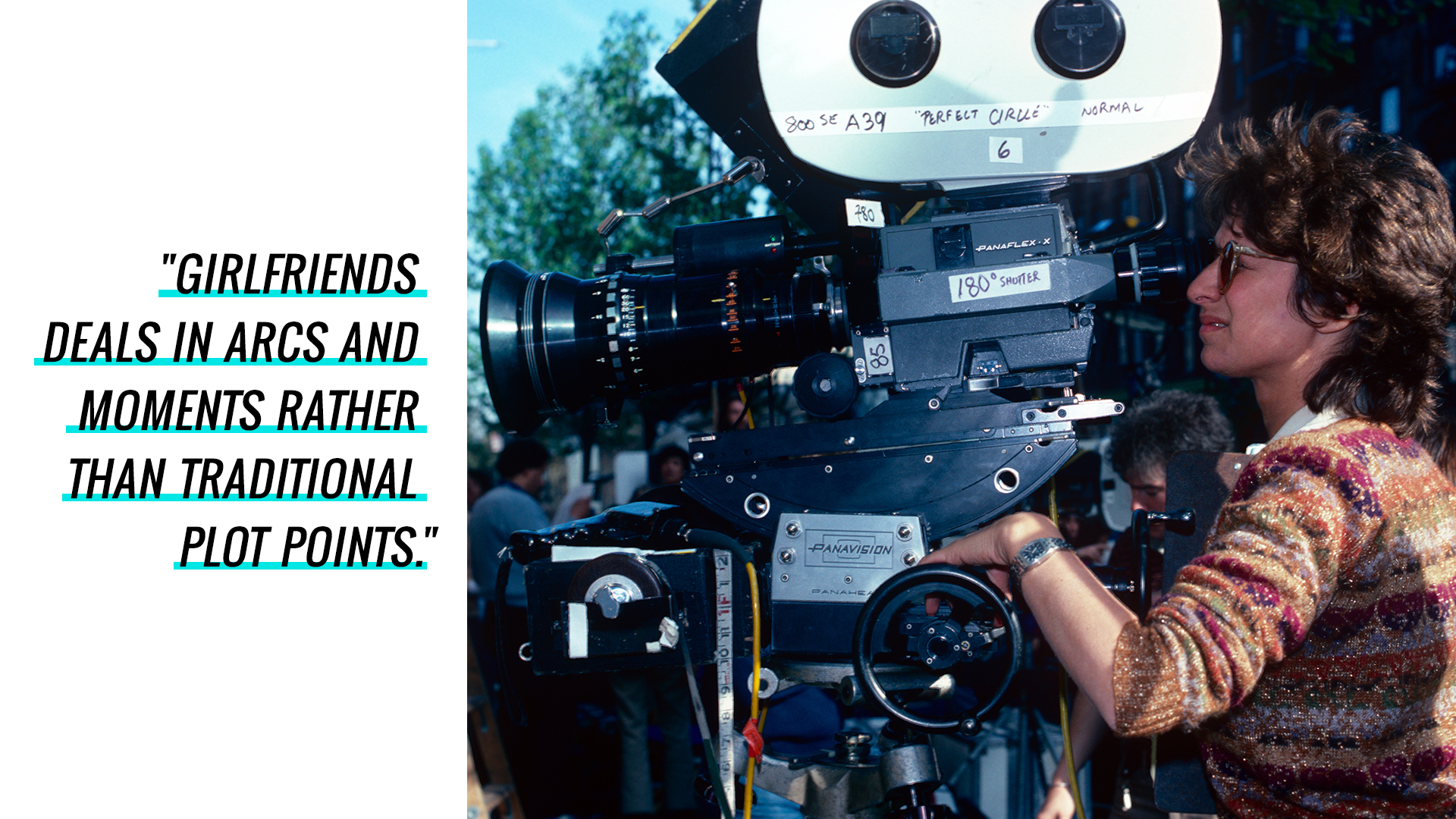

Tweed-wearing Manhattan intelligentsia may not be the first group to come to mind in a discussion about cult films, but this faction has had quite an influence over filmmakers and viewers for the past forty years. In 1978, only a year after the release of Annie Hall, a film called Girlfriends by writer/director Claudia Weill quietly premiered. Girlfriends focus on a photographer named Susan (played by Melanie Mayron) who must navigate Manhattan life after her roommate and best friend, Anne, gets married (to Bob Balaban, no less) and moves to the suburbs. Lesser scripts would focus on Susan’s on-again, off-again romances with her two suitors: a loveable prig (Christopher Guest) and a married rabbi (Eli Wallach). Girlfriends’ story centers around Susan confronting her loneliness, adjusting to the new architecture of her friendship with Anne, and making strides in her photography career – from chronicling bar mitzvahs to showcasing her work in a renowned gallery. Girlfriends deals in arcs and moments rather than traditional plot points. Susan contemplates putting yogurt in her mashed potatoes; she tries out a second roommate; she bluffs her way into important offices. When she forgets to tell the gallery owner which photos to hang in her first show, any other film would fetishize her mistake with a cringeworthy scene of tearful regret on opening night, but Susan’s subtle recognition and acceptance of her mistake is a breath of fresh feminist air.

The framework of Girlfriends may sound familiar. It is mirrored almost beat for beat in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha, wherein a twenty-something New York woman copes with the exodus of her friend/roommate, tackles her stalled dancing career and money difficulties, and only peripherally considers dating. Greta Gerwig, co-writer of Frances Ha, took up the Girlfriends mantle once more in her recent directorial debut, Lady Bird, with a compassionate focus on flawed characters and female friendship. It might be said that any screenwriter within the last forty years who have sidestepped cinematic tropes to create a female character who approaches obstacles with a droll smile and a self-assured reaction owes Girlfriends a considerable debt – from lesser-known works like Bill Forsyth’s Housekeeping to the ubiquitous hit Broad City. Girlfriends’ influence on modern television is perhaps most apparent in the HBO series Girls, which focuses on the careers, relationships, and foibles of a group of Millennial New Yorkers. Claudia Weill, the co-writer/director of Girlfriends, even directed an episode of Girls. More and more series, like Insecure and High Maintenance, are utilizing the Girlfriends blueprint of arc over plot, character over caricature, and humanity over histrionics.

Few films before Girlfriends featured a woman grappling with anything other than finding love or finding ways to prop up the men in her life. Within the world of most films, a woman’s career, artistic pursuits, and inner life were not just unfathomable to the point of invisibility; they were dangerous. Films that feature a female protagonist made before the enforcement of the Hays Code—which aimed to censor films deemed too “scandalous” or lacking “traditional values”—are branded as feminist because they often feature strong, independent women. But nearly all of these films end in marriage, backpedalling on every female advancement. Even when European films of the 1950s and 1960s featured women with agency, they were usually characterized as shrill loons (I’m looking at you, Ingmar Bergman). The long-suffering heroines of Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Naruse were strong beneath their tears, but there were usually tears. Girlfriends are arguably the first American film to portray a complex woman who was not being victimized by the world or herself. Part of that freedom is because the lead character exists after a game-changing wave of 1970s feminism (and because she is white, straight, and cisgender), but she is unphased by circumstances that would incapacitate a lesser character. The writers (Claudia Weill, along with Vicki Polon) chose to portray a woman who transcended the cheap dramatic beats of most movies with generosity and humour. A woman making it in the big city may seem like old news to modern audiences, but only because wry feminist gems such as Girlfriends paved the way for autonomous female characters, and proved that they could be deeply interesting and cult-worthy.

Check out these films that remind us of Girlfriends from Fandor’s library: Funny Ha Ha, 4 Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle, For the Plasma, Starlet.