[Editor’s note: This is the second piece of a two-part list, which was introduced earlier this week.]

It’s an unwritten law in the history of cinema that experimental—avant-garde, non-narrative—movies are fine as long they’re under twenty-five minutes or so. That’s about as long, it is thought, that even a seasoned cinephile can tolerate movieness without the progressive, empathic guiding hand of story. And it’s hardly an urban legend—ninety-nine percent of audiences demand narrative with their visual seductions, to the extent that for most people what’s vital about a movie is “what it’s about,” a state of affairs that has stood since 1903. For these masses the very idea of watching an 80 or 100 minute film that does not have a plot of some type is not only terrifying but flabbergasting—if it doesn’t tell a story, What does it do?

The question is the problem—for an experimental filmmaker, films don’t do, they are. To turn that train around, you have to try to reinvent the presumptions of the medium (which are, let’s face it, corporate capitalist at heart) and thereby liberate the form. Needless to say, watching a non-narrative feature isn’t passive—you put your game face on, send up your best antennae and consider moment to moment what movies are. Because they aren’t only what you thought they were.

8. The Falls (Peter Greenaway, 1980)

An OCD structuralist-fabulist in a class by himself, Brit filmmaker Peter Greenaway is more famous for The Draughtsman’s Contract, A Zed and Two Noughts and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, but his earlier, more hermetic films are equally fascinating, constructed in the abstracted-sand-castle tradition of Borges and Calvino. These fake histories and web-like chronicles of portent culminated in The Falls, a three-and-a-quarter-hour powerhouse display of imaginative dissonance, detailing the deranged effects of the V.U.E. (Violent Unknown Event) on the section of British population—ninety-two individuals, in fact—with names beginning with the letters F-A-L-L. Technically a mock-documentary and so therefore seemingly built around narrative discourse, The Falls is actually an intricate puzzle without a solution, and its web of elocutionary exposition is, in a rather Joycean way, more an exploration of language and and its discontents than an actual fiction.

9. Film Socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard, 2010)

The most recalcitrant of world-class auteurs, Godard has been making non-narrative features longer than any other filmmaker, starting at least from 1969’s Le Gai Savoir, standing outside of fashion for so long he comes close to defining a separate outlaw idea of what movies are. Made when he was eighty, Film Socialisme is just as filled with an octogenarian’s ambivalence and bitterness, and is by a notable stretch Godard’s most irascible film ever, a defiantly incohesive montage rumination on… maybe everything. He didn’t even subtitle the film’s French clearly—Godard mandated that truncated, elliptical “Navajo English” titles be used, two or three disconnected words at a time, so the unlucky monolingual viewers among us can get only the scantest ideas of what’s being said. Not that it matters—the floating monologues and exchanges often don’t match with the images at any rate, and are often obscured by ambient noise and the pervasive, menacingly sad score. Divided into three sections but insistently troubled by Palestine, Egypt and the legacy of Soviet rule in Odessa, the movie first prowls the decks and belly of a particularly garish Mediterranean luxury cruise ship, and secondly visits with a rural French gas-station-owning family suffering generational squabbles, and thirdly collapses into a free-for-all collage, obtusely glancing at imperialist history via film clips and stills, John Ford’s Indians to dead Palestinians to gladiator epics to Chaplin. Like all of his films, Film Socialisme is a conversation Godard has with us, naked, inconclusive, bristling with half-thoughts, jokes and sudden revelations, and each of us will walk away with a different exchange in our heads.

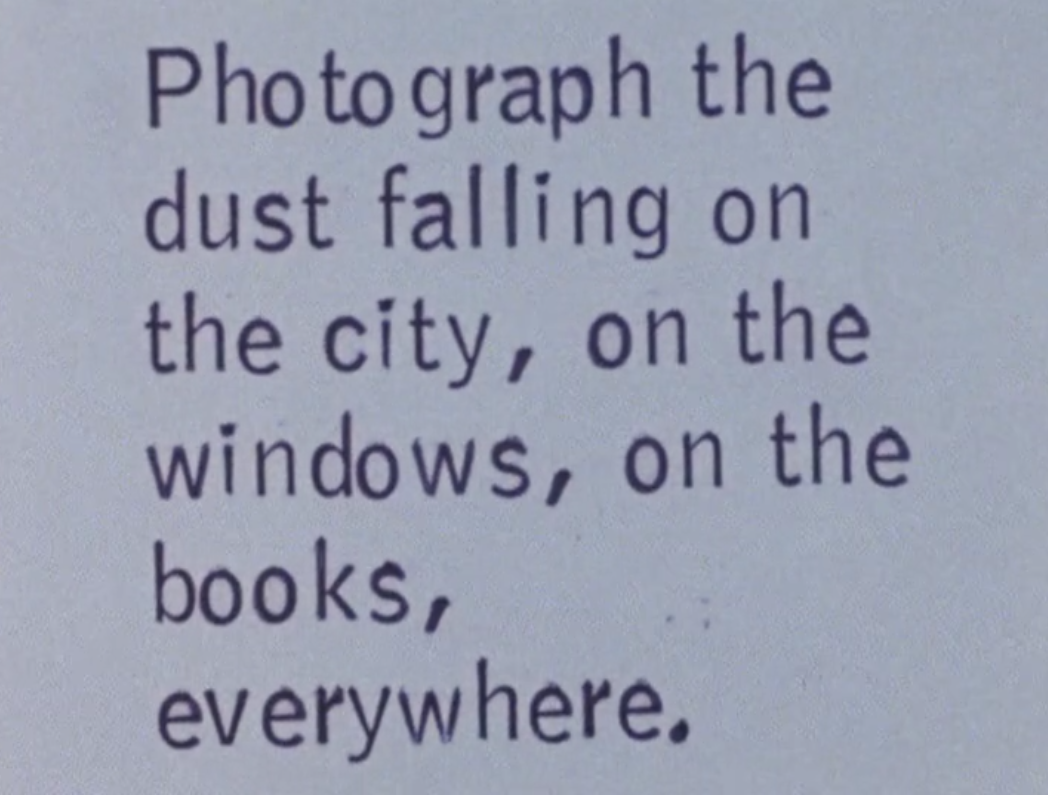

10. Zorns Lemma (Hollis Frampton, 1970)

Among the tribe of mid-century “New American Cinema” experimenters, Frampton never had the fame or cult reverence garnered by, say, Brakhage, Michael Snow, Gregory Markopoulos, Ken Jacobs, Jack Smith or Andy Warhol, before or after he died in 1984 (he was forty-eight), but he was an integral part of the scene, and his films survive as both intellectual provocations and emotional objects long after so much of the other work produced in the 1960s-70s seem pallid and fadingly hip today. This structuralist meditation, famously the first experimental feature to play at the New York Film Festival, is a hypnotic abecedarian collage that consists largely of one-second shots of public text, running from A to Z over and over hundreds of times, until the words are replaced one at a time by singular recurring images of work, nature and movement, until the language vanishes altogether. (“Zorn’s lemma” is an obscure set-theory “proposition”; Frampton was a bit of a math tourist.) Almost frame by frame, Frampton is interrogating the often outright combat between the intents of visual communication and the act of watching.

11. The Clock (Christian Marclay, 2010)

This monstrous, brutally clever construction—twenty-four hours of found footage, arranged around images of clocks and watches, which sync up to the actual time of the day—is so famous and recently celebrated it doesn’t need me to extol its virtues. My name is Legion, because I wish I’d thought of it.

12. The Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1974)

Everyone’s favorite cosmic-mise-en-scene Prometheus, palpably evoking a world of pregnant enigmas, intellectual angst and rainy-landscape atmosphere that is his alone, Tarkovsky only went fully avant-garde once, in this mid-career landmark, a free-form tone poem about childhood, fathers, mothers, lost loves, personal apocalypse, and the sheer rapture of Tarkovskiite visual alchemy. Scrambling childhood memories, domestic drama, dream fragments, atrocity newsreels, and poetry by Tarkovsky’s father Arseny, the film is uniquely personal, hermetic and moody, even by Tarkovsky’s standards. But the master’s magisterial visual style is such that it never been out of home-video print in this country.

13. Our Hitler: A Film from Germany (Hans-Jurgen Syberberg, 1977)

This infamous, seven-and-a-half-hour mega-opus was mostly a legend to stateside filmheads after its 1980, Francis Ford Coppola-shepherded U.S. premiere at the Ziegfeld Theater in Manhattan, and was finally DVDed in 2007. A kind of stagebound, Wagnerian discourse-voyage through the meanings and ramifications of Hitler’s place in the 20th century, the film is a “mosaic,” in Susan Sontag’s term, a salmagundi of theatrical effects, tropes, and set-pieces, and, purposefully, nothing is left out: puppet theater, re-enacted history, philosophical speculation, masquerade, vaudeville lampoon, Nazi film and audio clips, memoir recitations, symbolist tableaux, homages to German Expressionism, ad infinitum, all of it shot in a wreath of mist and in front of a giant projection screen in a cavernous Munich warehouse. Patience-testing and of course furiously inconclusive, Syberberg’s gargantua demands to be seen, if only as a responsibility and as a mark of hardcore art-cinema geekhood.

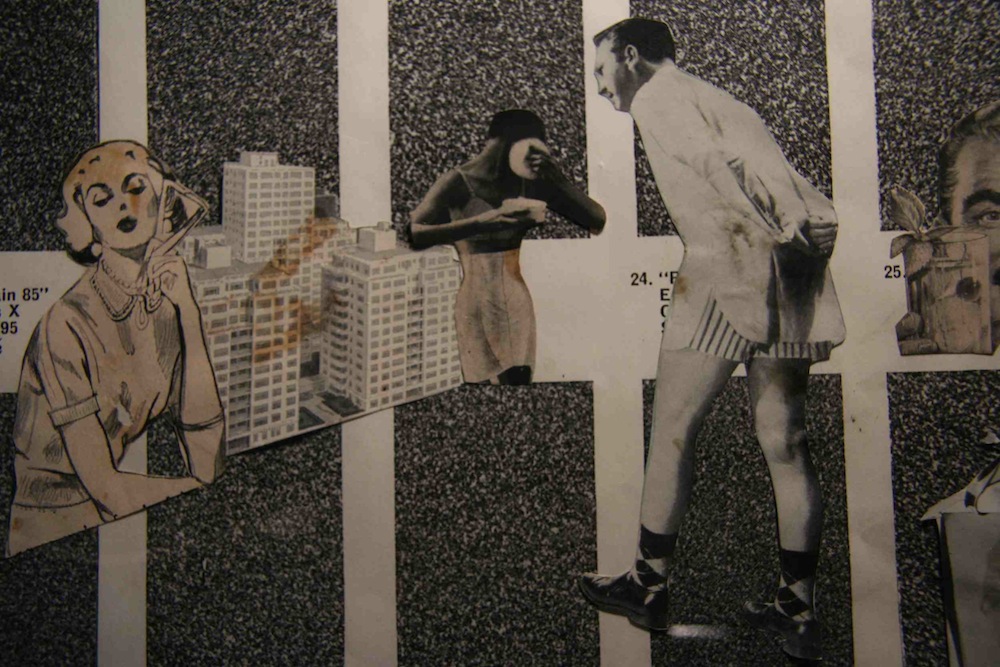

14. Tales of the Forgotten Future (Lewis Klahr, 1991)

A neglected but vividly inventive ransacker of the common culture junk drawer, Klahr constructs films out of animated magazine cut-outs and advertising images, which in his hands is a breathtakingly evocative trope. This twelve-part super-8 epic taps into the frustration, strangeness, delirium and dreary vertigo that lurks in the drywall of Middle America’s mid-century tract house; the “forgotten future” is, of course, the idyllic America of the post-WWII dream, a future that never actually happened, packed with images of dead fads and faded fashions: obsolete appliances, cheap furniture, garish wallpaper patterns, Steve McQueen-ish race cars, industrial futurism, luxurious department stores, all interrelated as if in a museum diorama. What keeps Tales from seeming quite as garage-made as it should is Klahr’s arresting manipulation of scale, theme and contrasting examples of high kitsch—in my favorite section, Elevator Music, jello molds and dish rack ad tableaus offset graphic suburban-confidential sex scenes Klahr shot himself. As dense and grotesquely beautiful as Klahr’s images can be, his soundtracks are true achievements, evocative layers of wind, whispers, industrial noise and, of course, elevator music. Never before has a filmmaker made so much from so little.

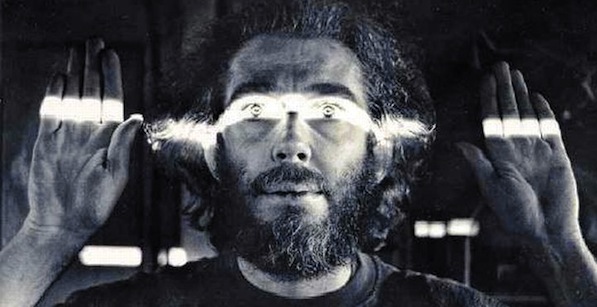

15. Diaries, Notes and Sketches (also known as Walden) (Jonas Mekas, 1969)

“New American Cinema” pope-king Jonas Mekas’s three-hour epic home movie portrait of the sixties may be the premier work of pro-am cinema-ship – home movies has always been mixed up with the legacy and syntax of underground film, as both forms take their power from the elegiac nature of film, the unprofessional beauty of found light and landscape, and the spontaneous energy of real life. Mekas himself apparently took his Bolex everywhere and filmed everybody and everything, and this three-hour diary-film is both an indelible time capsule and a distinctive portrait of the artist-with-a-camera. In a frantic weft of impressions (hardly a single shot stays still or lasts for more than a few seconds), the film documents the boho landscape of the time, peopled by the likes of Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, John & Yoko, Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, Peter Beard, Carl Dreyer, Barbet Schroeder, Edie Sedgwick, Timothy Leary, etc. The movie is never just a record of Mekas’s travels and daily lingering; it also hectically reimagines the world as a shake-&-bake cascade of sensations (with a free-associative soundtrack of old records, readings and subway racket). Whether we’re on the Bowery or at the Brakhages’ mountain cabin or at a lavish Newport wedding, Mekas’s take is jumbled, often double-paced, and strictly observational – the feeling is that this movie intends to keep up with daily events, instead of slowing them down and controlling the flow and turning them into something other than just life as it was lived.