Subterranean pope-king of secret histories and subversive reappropriation, filmmaker Craig Baldwin makes movies out of yesteryear’s garbage celluloid, films that are equal parts radical protests, investigative media-missiles, and pulpy play. As cinema they’re ironically sui generis, Frankenstein ogres rippling with cheap jokes, Freudian free-associations, and insurrectionary fury. Each time he redefines a chunk of bygone educational film or piece of government propaganda or Mexican horror flick, he is questioning what the images mean, emphasizing how absurd their original intentions were, and suggesting how their political power can be used not for oppressive evil but for good—or, at least, sardonic hijinks. Anti-establishmentarian and uncommercial to the bone, Baldwin is less pedantic than he is pulp-satiric, and as a result, the movies are endlessly dissectable, blooming with connections. His most famous film, Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1991), is also his masterpiece: a breathless, growling, fevered screed, in 99 chapters, that details the weaveworld of 20th-century history (and Central America in particular) as it has been influenced and manipulated by inner-earth-dwelling aliens called Quetzals. The story, illustrated by pirated sci-fi movies, military PSAs, TV commercials and school-science reels (this was in the pre-Google days, when Baldwin had to use actual discarded 16mm prints), intersects with the CIA, Howard Hughes, Fidel Castro (see as a skid-row Bible-class Jesus), Manuel Noriega, Ronald Reagan, Atlantis, Pinochet, Kissinger, E. Howard Hunt, the Mayan empire, United Fruit, the Bush family, Oliver North, and much, much more.

Only 48 minutes long, Baldwin’s film packs in enough looney ideas and sly comedy for four features; every cut and snippet is a layered joke, about American paranoia (the Quetzals are a clear satiric stand-in for “Communists,” a metaphoric trope that beautifully illustrates our fearful fantasies during the Cold War), as well as the very real conspiratorial establishment that has dominated politics in the postwar era. For purists, just the harried repurposing of orthodox film footage is enough of a rebel yell, and with this film, Baldwin had raised the bar on an entire school of experimental filmmaking, the kind that doesn’t use cameras. Tribulation 99 is satiric avant-garde intellectualism as action film (the nearest cultural corollary is with the novels of Thomas Pynchon, no minor comparison), and perhaps unique among “underground” films, it can be and should be seen several times, with each viewing paying off like a broken slot machine.

“Found footage” itself is a spellbinding subschool of cinematic expression, rising naturally and inevitably from the disposable film culture like saplings from a landfill. It’s been an established precinct of experimental filmmaking ever since Rose Hobart (1936-39), Joseph Cornell’s seminal reconfiguration of the 1931 programmer East of Borneo, of which, notoriously, Salvador Dali was so jealous he leapt into the booth during a screening and tore the film off the projector. Philosophically, found-footage filmmaking is an essential facet of our modern media lives, an inevitable culture rising from and acting contrapuntally to the mass media world we otherwise live in and often let control us. As per revered found footage vet Ken Jacobs, if we have come to think, dream and daydream in the syntax and iconography of movies, then excavating “lost” footage (the majority of film production as always been taken up with industrial, promotional, educational, religious and various other forms of “non-mainstream” cinema) can be considered akin to psychoanalysis—culture studies at its most therapeutic.

As per revered found footage vet Ken Jacobs, if we have come to think, dream and daydream in the syntax and iconography of movies, then excavating “lost” footage (the majority of film production as always been taken up with industrial, promotional, educational, religious and various other forms of “non-mainstream” cinema) can be considered akin to psychoanalysis—culture studies at its most therapeutic.

Indeed, it’s the only brand of movie in which every frame has two often conflicting authorial intentions, forcing each image to be non-definitive—the many pieces of dislocated imagery in Bruce Conner’s pivotal A Movie (1958) no longer belong exclusively to their sources, nor do they belong exclusively to A Movie. By decontextualizing cinematic fragments, filmmakers like Conner send them into a free-associative abyss, where they can signify nearly anything in nearly any context.

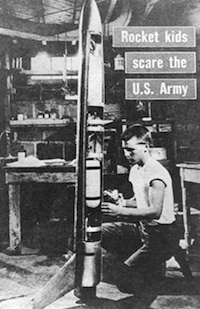

No one has taken this politically loaded aesthetic further than Baldwin. His first mature film was RocketKitKongoKit (1985), an incisive historical firecracker that set the mold for his politically incendiary subsequent work: willfully harebrained found images are coupled with authentic, disturbing news footage of Zaire under Mobutu’s reign, supported by a just-the-facts narration of Mobutu’s step-by-step exploitation of his country and ties to foreign governments, including ours. Coming soon after Tribulation, O No Coronado! (1992) continued Baldwin’s interrogative course, this time reconstructing the historiography surrounding the Spanish conquest of the New World as personified, in all his disaster-prone, loot-and-kill buffoonery, by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who journeyed across Mexico and the Southwest searching haplessly for the Seven Cities of Gold, a trek marked by tragedy, cannibalism, wholesale slaughter and madness. Simultaneously a risible, factually accurate chronicle of Coronado’s mishaps (one every schoolkid should see) and an outright parody of cinematic historicization (Baldwin pillages countless costume dramas and swashbucklers, as well as picture books, serials, Gulliver’s Travels and kitschy re-enactments Baldwin shot himself), Coronado! is an object lesson in how to revivify the most moribund cinematic avenues. If only Baldwin had been commissioned to make J. Edgar, Che or The King’s Speech.

Sonic Outlaws (1995) was a slightly different beast—a more-or-less orthodox documentary about piracy media, consumerist rebellion, and the Negativland-U2 scandal, featuring investigative interviews and news footage (used straight), but contextualized by a Gatling-gun montage of cannibalistic scrap-film referents. On the most basic level it’s a thumbnail portrait of an entire secret subculture, one of record sampling, pirate radio, retail sabotage (it’s hard to resist the tale of the Barbie Liberation Front, a group of snarky radicals who would steal talking Barbie and G.I. Joe dolls, switch their voice discs, and then return them to store shelves), the anti-corporate ethics of “retournage,” and so on. But thanks to Baldwin’s spirited interpolations and editing wit it’s a rousing and hilarious document of anti-corporate anger and action. Spectres of the Spectrum (1999), on the other hand, is more classically, hermetically Baldwin, whipping original footage of ranting revolutionaries of the future in with a mountain of advertising film, government reels, cheapjack features and forgotten TV shows, rewriting 20th-century history as a struggle for control over electromagnetic media, from radio to the Internet—that is, control over radiation itself.

A risible, factually accurate chronicle of Coronado’s mishaps (one every schoolkid should see) and an outright parody of cinematic historicization (Baldwin pillages countless costume dramas and swashbucklers, as well as picture books, serials, ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ and kitschy re-enactments Baldwin shot himself), ‘O No Coronado!’ is an object lesson in how to revivify the most moribund cinematic avenues. If only Baldwin had been commissioned to make ‘J. Edgar,’ ‘Che,’ or ‘The King’s Speech.’

Baldwin’s latest, Mock Up on Mu (2008), is on another planet altogether—or moon, or space station, and actually you can never be sure it is anywhere at all. Incorporating copious new footage into his free-associative mix of old pulp, educational film, et al., Baldwin here fashions a “not untrue saga” (according to its proliferating titles and non-stop, multi-voice narrations) that wormholes through the origins of Scientology, bopping back and forth from the postwar past and the indeterminately cosmic future, as both are, I think and I’ve seen it twice, affected or determined by the pentagrammatical influence of, in turn, Aleister Crowley, L. Ron Hubbard, Jet Propulsion Lab co-founder and occult wingnut Jack Parsons, aerospace manufacturer Lockheed Martin (here personified by a person named “Lockheed Martin”), and New Age progenitor Marjorie Cameron. It is indeed not untrue: the sexual/mystical/financial history of Parsons, Cameron (both Crowley devotees) and Hubbard in the 1940s makes for stampede reading wherever you find it, but of course Baldwin fictionalizes the characters’ wacko ambitions into “reality,” cheesily invoking Hubbard’s blowhard pseudo-ideas about the future of the human race. At its least, it’s a fugue of speculations voiced by psychotic characters and illustrated by hunks of Star Trek, Things to Come, Logan’s Run, THX 1138, industrial project films, real news footage, NASA clips, Kenneth Anger images (borrowed and recreated, including shots of Cameron from Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome), and an uncatalogable river of other materials, which is to say the movie often succumbs to megalomaniacal confusion, befitting its subject.

As of this writing, Baldwin reports that he is at work on a feature exploration of the uncanny, meta-coincidental nexus within a five-block radius in the Left Bank neighborhood of Paris in the late ’50s between fellow radical collagists William S. Burroughs and Guy Debord. (Anyone interested in a preview of his ideas about this aboriginal spawn of anti-media may appreciate Baldwin’s keynote speech [vimeo.com/39706359 ] given at the Ann Arbor Film Festival this April.) The resulting film, he assures us, will not be anything like a “traditional” biopic.