[Editor’s note: Fandor publishes Mark Rappaport’s Becoming Anita Ekberg today.]

It’s not easy, being a sex goddess. It’s a lot of work and it’s not always pretty. Being tall, blonde and statuesque—a euphemism, if ever there was one—isn’t nearly enough. There have been plenty who have perished by the roadside in this long perilous journey—often to nowhere. Being Swedish, although sometimes an advantage, is not always enough either. First, you have to have a promoter or a Svengali or a producer, call him what you will, who will take you in hand and create or find vehicles for you. Anita Ekberg was very lucky that way. Twice. First there was Frank Tashlin, who made her into a recognizable commodity. Then there was Federico Fellini, who made her into a goddess, albeit for a short time only. Second, once the Svengali steps or is pushed aside, the bona fide sex goddess has to make it on her own. In other words, there has to be some kind of universal consensus that she is indeed a goddess and not some faux-goddess dreamt up as a publicity stunt.

When Tashlin first cast her as “Anita” in Artists and Models (1955), she was virtually unknown. Her most significant role up to that point was in William Wellman’s grim John Wayne action movie, an unentertaining Cold War entertainment, Blood Alley, also made in1955, in which she plays a Chinese peasant (!) fleeing from the Commies. She wears a woolen cap covering her blonde hair and plays Mike Mazurki’s wife! If you blink, you’ll miss her. Whether the character’s name in Artists and Models was “Anita” before she was cast or changed after she was cast, we’ll never know. Perhaps it was an attempt to build up her audience-recognition factor by identifying the actress with the name of the character she was playing so that the audience’s chances of remembering her in the future would be enhanced. The same may have been true of Silvana Mangano when she played “Silvana” in Bitter Rice.

In any case, in Artists and Models, Anita as “Anita” is billed seventh, after Martin and Lewis, Dorothy Malone, Shirley MacLaine, Eddie Mayehoff, and Eva Gabor. She is a mere one notch above George “Foghorn” Winslow—the precocious ten-year-old who refers, much too knowingly, to Marilyn Monroe’s “animal magnetism” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. By now he is twelve. She has very little to do in the film. At the climactic Artist’s and Models Ball she is scantily clad, and Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis paint something on her back. By the smile of pleasure on her face, as they are doing it, we suspect and certainly hope that it’s something very naughty. When she turns her back to the audience so that we can see their handiwork, we see that it’s nothing more risqué than a game of tic-tac-toe. Other than that, she merely just serves as a foil for Dorothy Malone, who goes into smolder and slow-burn mode whenever Anita Ekberg comes near Dean Martin.

The movie made her neither famous nor infamous, but exactly a year later she appears as herself, as that very famous movie star, “Anita Ekberg,” in Tashlin’s Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis vehicle Hollywood or Bust. (Both films were Christmas releases in their respective years, 1955 and 1956.) The innuendo in the title was not exactly lost on the movie-going public, but the fifties in America was a time of such widespread sexual repression that even remarking on the title’s implicit vulgarity would boomerang on whomever might acknowledge it. Better not to notice such things, or give voice to them if you do. In between the two Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis movies, Ekberg appeared in a grade-B potboiler, Back From Eternity, as a bad girl on an airplane that crashes in the jungle and had a smallish role in King Vidor’s War and Peace, as Vittorio Gassman’s sister and Henry Fonda’s money-grasping, frivolous wife. Well, why not? She’s Swedish, Gassman is Italian. They’re every bit as Russian as Audrey Hepburn or Henry Fonda. Neither of the films made Ekberg into a star. It is Tashlin himself who makes Ekberg into a star simply by virtue of referring to her as one in Hollywood or Bust. If being a movie star is an artificial construct, so is playing a movie star when you’re not one, even if the character has your name. If Artists and Models is the annunciator, Ekberg’s role in Hollywood or Bust is the star it is pointing the way to, and of course Tashlin is the omniscient god who makes it all possible.

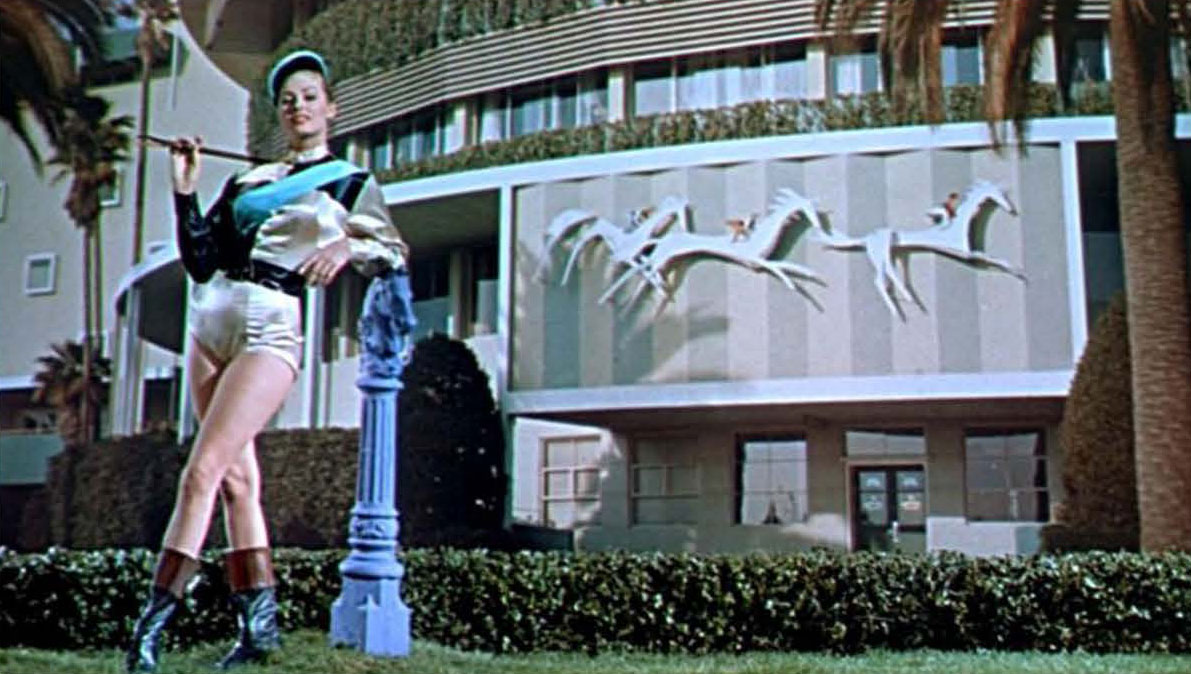

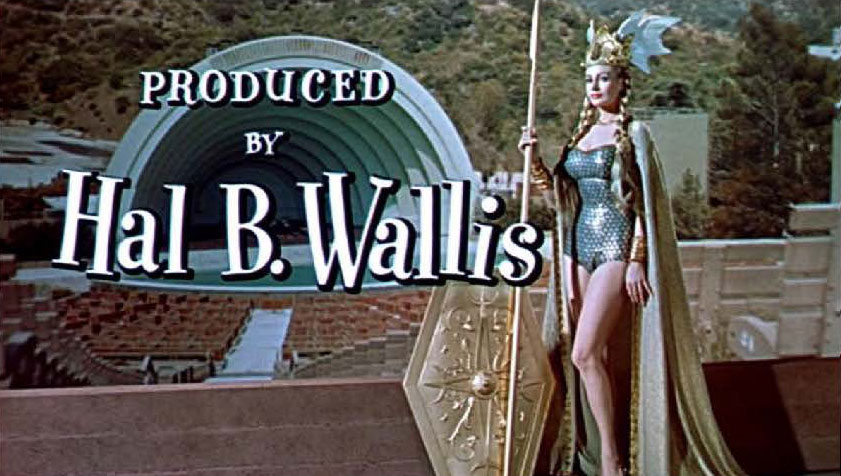

In Hollywood or Bust, even though she is listed as a “Guest Star,” she has the decidedly ignominious chore of being decoratively clad in the title sequence in thirteen different tableaux, posed, as if she is in a postcard, in front of a variety of Los Angeles hot spots. She appears in a kitschy, bare-legged oriental costume in front of Graumann’s Chinese Theater. She is in front of Romanoff’s costumed as a Cossack complete with whip and boots, wearing shorts, of course. She is on a Western street scene complete with cowboy hat, leather vest and fringed mini-skirt, posed as a jockey in front of Hialeah, sporting a jockey hat, riding crop and hot pants, in front of the Brown Derby bare-legged in a soubrette’s uniform and, most hilariously and fetishistically of all, in front of the Hollywood Bowl dressed as a Valkyrie, with long blonde braids, a winged helmet, a one-piece bathing suit, and accompanying Valhalla accessories—a gold shield and a staff. Her image, fittingly enough, accompanies the credit of Hal Wallis, the producer of the film.

This is not much of a promotion from Artists and Models, whose main titles feature similarly scantily clad models seductively posing on the sides of the various credit title cards. In fact, she is assigned similar duties in the credit sequence of Artists and Models. However, despite being treated as a lowly extra in the opening or Hollywood or Bust, it is her presence, and significant absence, in the first three-quarters of the film, that gives the movie its raison d’être.

In Hollywood or Bust, Jerry Lewis is the paradigm of the movie-crazy nerd who lives for nothing but the movies. He can roll off the list of (fabricated) movie credits of everything he’s ever seen and peppers his conversation with analogies to scenes from Paramount movies. He so desperately wants to win a free car that a movie theater is giving away as its raffle prize, in order to drive cross-country to meet his favorite movie star…Anita Ekberg, that he buys up all the raffle tickets. He is such a devoted fan, he saw her last movie six times. (The movie is called “The Lavender Tattoo-er,” possibly a lost Tashlin, and I suspect that there are a bunch of us who would pay a modest king’s ransom to see that film.) Much like the character of Sacha Baron Cohen as Borat, in Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, traveling across America stalking Pamela Anderson and having all kinds of adventures along the way, Jerry heads out to find his dream woman, although he’s not quite the rapist and kidnapper Borat is, not that he wouldn’t like to be or couldn’t be, had he been a comedy star in a more enlightened era. Like ours, for example.

In the beginning of the film there are a couple of tasteless jokes about Anita’s endowments aimed at the Martin and Lewis target audience—boys from the ages of nine through fifteen. But the closer the movie gets to Anita and the Hollywood (or Bust) of the title, the jokes get more and more chaste so as not to leave the impression that anything untoward could actually happen between the developmentally adolescent Jerry and Anita. Dean, meanwhile, has found his girl in their cross-country wanderings, the pertly wholesome but mostly annoying Pat Crowley, the kind of girl Jerry usually winds up with in their films. Jerry, it should be added, has, as his constant traveling companion, an obnoxious great dane called Mr. Bascom, the kind of dog that one usually suspects people own for sexual purposes only. One scene in particular makes this fairly clear, although, again, if you had pointed it out at the time, the onus would have been on you and your dirty mind. Crowley and Martin are sleeping outdoors, sharing a blanket. Martin, unable to sleep, gets up and cedes his place to Mr. Bascom, who rhythmically thumps Pat Crowley with his tail. Crowley, thinking it is Martin, and clearly his ill-behaved and probably enormous erection—what else could she think it is?—is outraged. In other words, Mr. Bascom is the erect penis Jerry Lewis is not permitted to have.

Jerry and Mr Bascom accidentally stumble on Anita Ekberg and her daintily manicured toy poodle, DuBarry, when they make an unexpected pit stop in Las Vegas. (One of the marquees of the hotels they pass, The Sands, in an exuberant burst of post-modernism before-the-fact, has Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis listed as their star attraction). Jerry’s great dane and Anita’s poodle, in the film’s most improbable fiction, “fall in love.” The shy, recessive, passive-aggressive Jerry has an enormous dog with a probably equally enormous erection and Anita Ekberg, a man-devouring, sex machine created solely for the purpose of exciting men, has a dainty little poodle. Their animals are fun-house mirror reversals of the characters they project. The potentially dangerous and most incongruous sexual coupling of Jerry and Anita is defused by having their unlikely surrogate dogs play out the mating game as a cartoon rather than as sexual passion. Even though Anita tells Jerry to get lost in no uncertain terms, she later tells her shrink that her poodle has fallen hopelessly in love with Mr. Bascom and she, Anita, must find Jerry’s dog, for the sake of her and her dog’s happiness. Through a comedy of errors including a manic chase through various film sets on the Paramount back lot, which will serve as the model for Pee Wee Herman’s slapstick pursuit of his stolen bike through half a dozen movie sets in Tim Burton’s Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, Anita and Jerry, Dean and Pat have all reconciled. The four of them attend the premiere of Anita’s latest movie, “The Lady and the Great Dane” (no, not Hamlet, although maybe that, too, but, even more importantly, in terms of pop-cultural relevance, a gloss on Disney’s hugely successful, The Lady and the Tramp of the previous year), starring Anita and Mr. Bascom. The two human couples appear arm-in-arm and arm-in-arm, typical of the endings in Tashlin’s movies of the period (cf. The Girl Can’t Help It, Artists and Models, and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?).

This was Ekberg’s big chance and Tashlin did indeed turn her into a famous sexual commodity. But not a star, as the following eight movies she made between 1956 and 1959 attest. Fellini, however, appropriates the Tashlin fiction of Anita and goes him one better. In La Dolce Vita, Sylvia, the American movie star that Ekberg plays, or, rather, inhabits is not only a movie star and sex symbol, she is indeed a Sex Goddess, the Eternal Feminine, every man’s dream. Certainly Marcello’s, played by Marcello Mastroanni. When Marcello is allowed to engage in whatever fantasies he wishes about her, she is the almost-attainable, unattainable goddess come to earth. “You’re everything, everything.” He elaborates breathlessly, ”You’re the first woman of creation, Mother, Sister, Lover, Friend, Angel, Devil, Earth, Home,” as if he is in a trance, reciting a laundry list of what he is looking for in a woman.

When she returns to her hotel at dawn, her jealous American boyfriend, Robert (Lex Barker) slaps her and makes her cry. Confer Bob Dylan here: “She makes love just like a woman/…But she breaks like a little girl.” Movie star by day, Goddess at night, whimpering, insecure girl at dawn. For all her sex goddess attributes, she permits herself to be treated very poorly by her boyfriend, who is clearly not as enamored of or as intimidated by her beauty as he once was. This is another aspect of being a Sex Goddess. Never get off that pedestal.

The man who plays her boyfriend in La Dolce Vita was moderately successful and had had something of a career. Lex Barker had been the tenth, and arguably the most handsome Tarzan of them all. He was equally famous for his string of beautiful wives—Arlene Dahl, followed by Lana Turner, although Cheryl Crane, Lana Turner’s daughter, says in her autobiography Detour, that he repeatedly and brutally raped her during the almost three and a half years that he was married to Turner. Crane was ten years old when Barker and Turner got married. Later, Barker would become immortal, at least to young German boys, by playing Old Shatterhand in a series of movies based on Karl Mai’s classic children’s novel about the American West—about which he, Mai, knew absolutely nothing, never having traveled to America. The ironies abound.

Providing Sex Goddesses with genuine Sex Goddess moments in their films is a formidable task. It usually works better in still photos, where the frozen moment can be endlessly replayed in the imagination, or studied and memorized, than it does in live-action real time. Rita Hayworth in her “Put the Blame on Mame” number in Gilda, Monroe in her now-famous white halter-top dress standing over the subway grill waiting for the passing subway to blow her skirt up in The Seven Year Itch—these are carefully calculated events, and their success had not only been foreseen but planned, hoped for, and expected—although, paradoxically, the famous shot of Monroe’s billowing skirt does not exist in the film, but only as a publicity still. These scenes capitalized on the charms and fame of the stars in the hopes that these newly created environments would ratchet up the stars’ value as sex goddesses even further, would provide yet another set piece which male viewers could utilize in their fantasies. Anita’s presence in Fellini’s fountain—let us face it, it’s no longer the fontana di Trevi but the fontana di Anita or the fontana di Fellini—was an unforeseen success in the Sex Goddess sweepstakes, and all the more exciting for that. Unexpected, unplanned—and overwhelming. A star was indeed born. Anita, in a slightly less showy or self-conscious way than Rita or Marilyn, unexpectedly captured the hearts and minds, not to mention wet dreams, of the Western world.

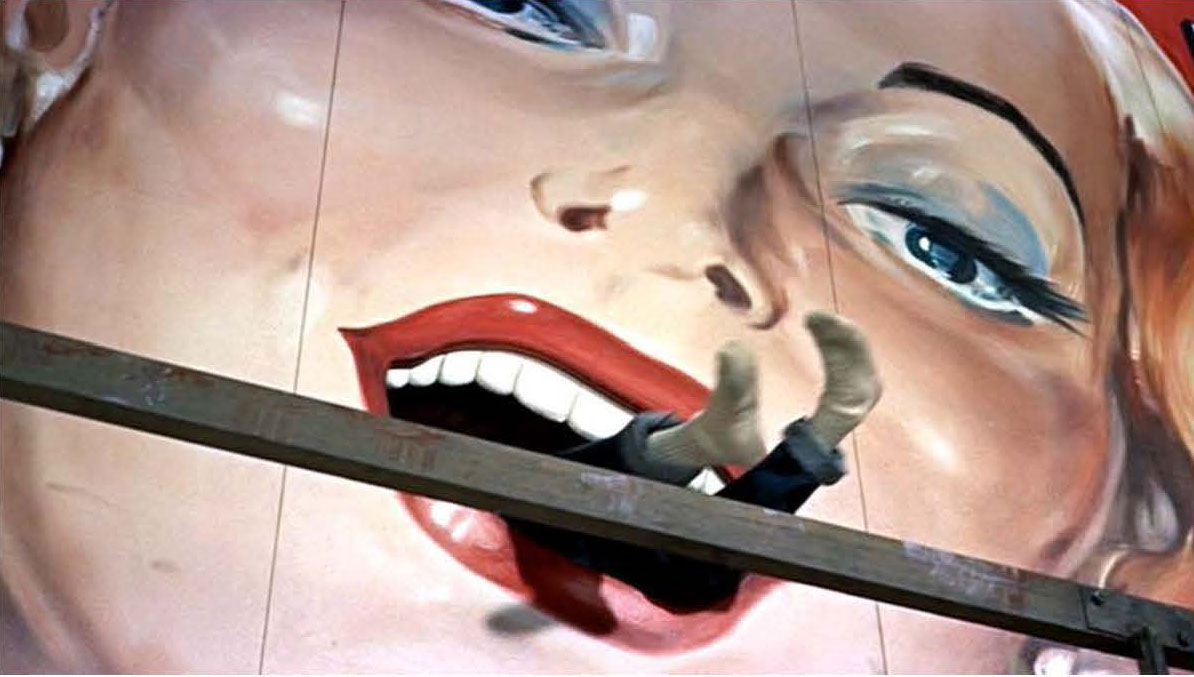

But the apotheosis of Anita Ekberg is in Fellini’s “The Temptation of Dr. Antonio,” Fellini’s medium-length episode in Boccaccio ’70. Her fame precedes her character. Here, again, she is “Anita Ekberg,” but this time she really is Anita Ekberg, lending her name, face, and body to an advertising campaign, advertising…nothing. The real Anita Ekberg, whoever that may be, if she ever existed at all, is now a glorified concept. Like Gladys Glover, the character Judy Holiday plays in Cukor’s It Should Happen to You, she gets a billboard of her very own. But unlike Gladys, Anita knows what to do with her notoriety and how to fill her Cinemascope-shaped billboard. Here she is the begowned, uninhibited Goddess of every man’s dream, if only he had the courage to dream her, lounging languorously on her couch, or is it her throne? inviting men to their doom. (Even when Dr. Antonio complains about her, he compares her to Semiramis, Cleopatra, and Thaïs.)

She is the Frank Tashlin-influenced fantasy to the nth power. Not only is she Anita Ekberg in Hollywood or Bust but she is also Tashlin’s Jayne Mansfield holding the exploding milk bottles to her bosoms in The Girl Can’t Help It. Here she is a larger-than-life billboard image seductively advertising milk—although peddling milk is a mere afterthought. She is a pair of outsized mammary glands run amok. She is the owner of the disembodied, sensually parted lips Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, the billboard painters, are painting at the very beginning of Artists and Models.

She is Woman, writ very large, too much for any one man to handle, much less the milquetoast, hysterical, sexually-repressed Dr. Antonio (Peppino de Felippo), who almost suffocates in her cleavage. She is the woman whose much-larger-than-life vagina the seemingly mild-mannered rapist in Almodóvar’s Talk to Her disappears into, in the film-within-the film, never to be heard from again. She is the seductive pair of billboard-sized lips that swallow up Jerry Lewis in Artists and Models.

The impossibility of ever sexually satisfying her renders her supplicants either permanently priapic, like Marcello—to little avail—or, more likely, impotent. She is the symbol of the all-powerful female who makes the insignificant male cower and shrink before her daunting, overwhelming femaleness. In a pre-feminist role-reversal, Queen Kong—the Revenge of the Blondes—has a Lilliputian-sized man pursue her until he catches her and he flips out, partially because he’s unable to deal with her overly abundant pulchritude. If Myra Breckenridge, Embodiment of the Female Principle, She Who Must Be Obeyed, Destroyer of Men, were indeed possible, this is whom she would be—the Milk Woman as played by Anita Ekberg.

Where do you go from here? Obviously no place but down. Ekberg has been taking rent-paying jobs ever since Boccaccio ’70, but Tashlin in a sense used her up and Fellini brought her to unimagined heights, on a billboard on Mount Olympus from which there was no turning back. Or coming down, although she literally does step down from her billboard pedestal. Tashlin created a “star,” Fellini a myth. Fellini took the largeness that was Anita and made it so large that she could never fit into it again.

There’s an epilogue to both the Tashlin and Fellini movies. Ekberg appears in Tashlin’s The Alphabet Murders, in the sixties, but not in a part designed for her or one that specifically requires her Anita-ness. It’s a part that anyone could have done and does not refer to the myth of her myth in any way. She appears again in Fellini’s Intervista, when Fellini project’s the Trevi Fountain scenes for her and Mastroianni. It’s a sad scene, shot over twenty-seven years and several life times after La Dolce Vita. One tries not to gasp, seeing Anita. She is barely recognizable. He voice has become a husky, rasping baritone and she looks more like a blonde Saraghina than a time-scarred Sylvia. A sad footnote to the myth Fellini created, as sad, in fact, as Intervista is in relation to La Dolce Vita or 8 1/2.

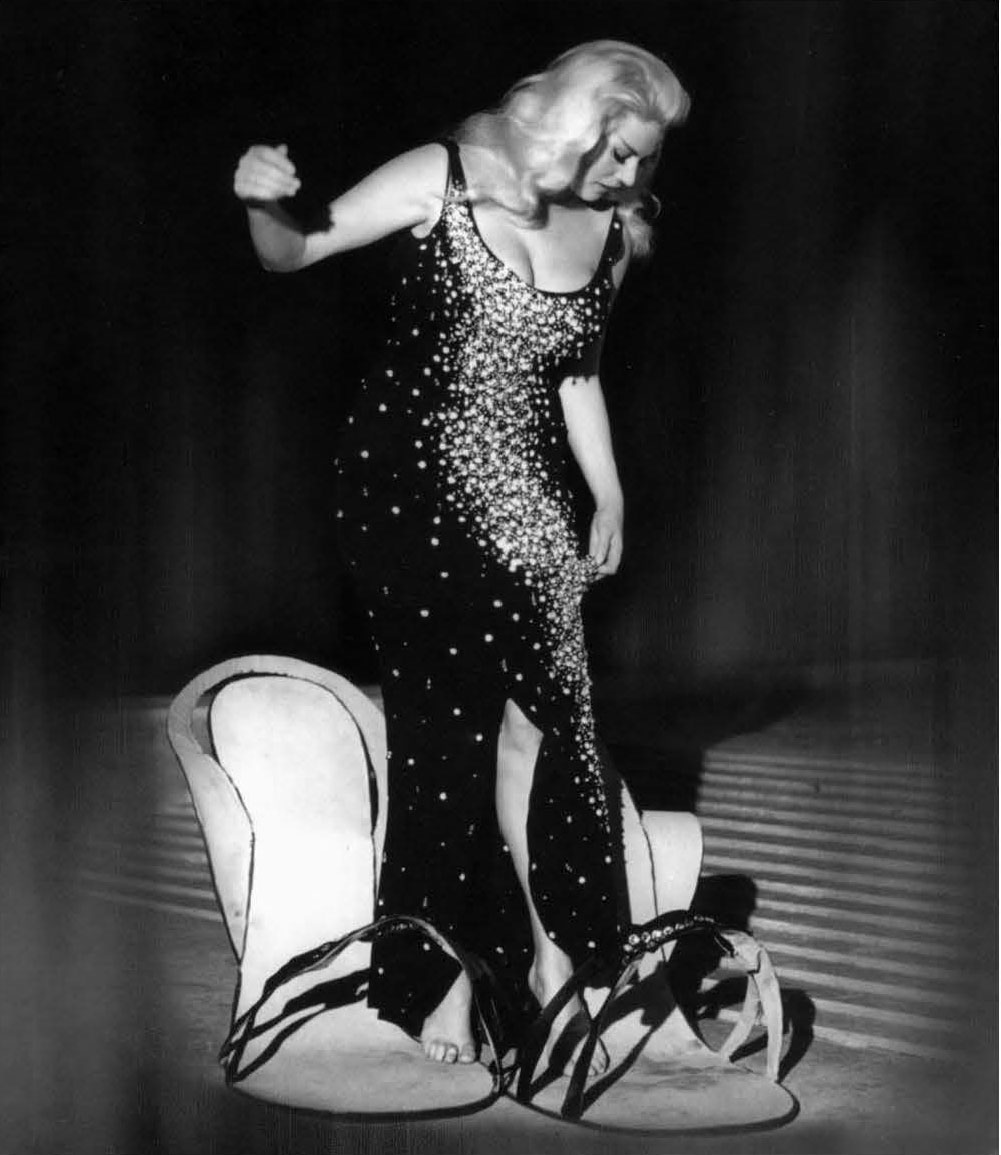

On the box cover of the European DVD of Boccaccio ’70 there is a publicity still that, alas, does not appear in the movie. The ordinary life-sized Anita is standing in the high-heeled sandals props that the giant Anita kicked off. A reminder that no one can really fill the shoes, however skimpy, of a Sex Goddess for very long. Not even Anita herself.