You almost certainly know the story, no matter what the extent of your direct exposure to the source material may be. Alice is a young girl who follows a white rabbit into a mystery realm of discombobulating extremes: cute creatures are often revealed to be devious and cunningly vicious, while a Queen of cards orders executions with a sense of flamboyantly entitled haste that resonates regardless of your familiarity with the Victorian era that the author savagely parodied (barely disguised dictatorships know no cultural bounds, after all). Even at its cutest, Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland reveled in the danger of fantasy, in its possibilities for symbolic protest, as well as for unstable explorations of the human id, particularly at its near infancy.

That last sentiment is more important to consider now than perhaps ever before, particularly for contemporary American audiences who’ve been conditioned to equate fantasy arbitrarily with action, as in big budgeted, self-consciously grandiose “tent-pole” films that pilfer fantasy elements willy-nilly, usually at the service of a message that runs explicitly counter to the subterranean meanings offered up in something like the original story of Alice in Wonderland. In these films, characters often travel to faraway places only to discover, normally after conquering and enslaving a species of choice, that there’s nothing quite like the reassuring stability of home, of stasis, of implied blinding allegiance to the father-figure of the house who represents, by extension, the larger authority of society.

Let’s set aside the moral dubiousness of these bombastic thematic tendencies, particularly as manifested within the culture of a country notorious for making global war of intensely debatable necessity, as there are many potential books on that subject alone. This kind of blunt, stripped-down, self-entitled hero fantasy also sadly compromises the existence and mysteries of any child’s inner life: especially of blossoming sexuality, and of aggression, as directed shapelessly at all the sources of a child’s attractions and frustrations.

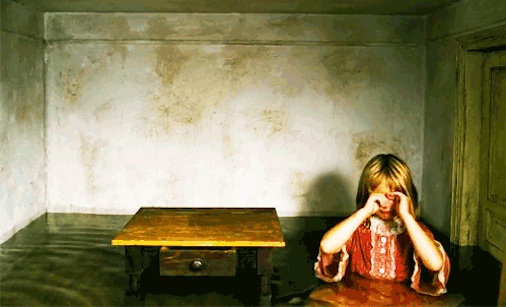

Jan Švankmajer’s Alice is a great film without these contexts, but to revisit it in this present American pop cultural dimension is to feel nearly blessed by its calm, reassuring sanity and beautiful curiosity. As the title indicates (though the original Czech title Něco z Alenky roughly translates to the more suggestive and revealing “Something from Alice”), Švankmajer’s film is a pared work that emphasizes the girl of the title at the expense of her normally requisite wonderland. What will immediately strike viewers, particularly those new to the claustrophobia of the director’s work, is the fact that Alice, played by the eerily poised Kristýna Kohoutová, never seems to really go anywhere. Her wonderland appears to be composed of the empty rooms of her house, and maybe of the nearby sheds that have been potentially erected on her family’s property.

But you never know that for sure, because Švankmajer doesn’t offer the usual “real” first act meant to provide the viewer with conventional orientation so as to allow an either/or, compare/contrast of fantasy with reality. There are a few opening shots, presumably in the real world, that most memorably show Alice tossing stones into a body of water, which segues into a corresponding image of her tossing stones into a half-full cup of tea. This juxtaposition serves to succinctly establish her longing for something “other” at the possible potential expense of her life of stifling stability. But this Alice’s wonderland never, strikingly, embodies freedom as an attainable goal, as this land is composed of often cramped rooms that appear to be, sometimes literally, squeezing down upon Alice. We’re never whisked away from Alice’s reality (or, depending on your read of the film, we never leave her fantasy); we’re never invited to forget that her adventures are essentially her daydreams enabled with a bit of perversely inventive puppetry. Which is to say that we’re never allowed to forget from where these fantasies initially sprang: from Alice’s mind.

Is Alice in danger? Is she wandering abandoned buildings, fashioning a day’s play from their detritus of nails and loose boards, from the dried skeletons of dead animals who’re re-born, in her mind, as various legendary characters such as the Caterpillar and the Mad Hatter? Or, perhaps even worse, is this her home, a squat place of poverty, barely tended by much-needed adult guardians? Or is this a more literal wonderland, re-envisioned by the director as a land of the dead and of unrelieved hysteria and blossoming sexual anxiety? Or is a gifted child making just a bit of simple mischief that indicates little apart from the no-so-delicate breadth of her imagination? Any, or maybe many, of these explanations are justifiable. But the ambiguity of the fantasy’s source restores to fantasy a stream- of-conscious sense of chaos.

Alice’s adventures here aren’t delightful in the typical sense of that word. Švankmajer conveys an understanding of child’s play as it often is rather than as parents might hope to believe it to be. Alice consumes things, or plays at consuming things, that alter her body and allow her to explore notions of death and, in one prolonged and remarkable vignette, of extended domestic violation. Her adventures reflect the purity of a child’s morbidity, before social institutions have instilled in her the proper reliance upon condescending platitudes when faced with death. Things in this wonderland die but spring back, often re-contextualized and re-contorted, because death for a child is an abstract principle to be toyed and jousted with as well as casually re-defined. The creatures, which occasionally recall the paintings of Georgia O’Keefe, are almost comfortingly hideous: beyond the endearingly amoral, self-cannibalistic initially stuffed rabbit, there are fusions of alligators and chickens and frogs that emit amusingly grotesque sounds of creaking, screeching and breaking, and that move with a tender jerkiness, traditional of low-budget stop-motion, that seems to testify to their matter-of-fact will over inertia and decomposition. This very jerkiness even registers as thematically apropos: We’re seeing the work of imagination, the palpable flexing of muscles both literal and figurative. Above all, these creatures are fiercely tangible, regardless of the fluidity and disagreeability of the reality that enfolds them; simultaneously works of still life and of motion poetry.

And, for that poetry, Alice isn’t bleak or nihilistic. A joy springs from a work that’s so clear-eyed of childhood (and, by extension, humanity entire). Švankmajer isn’t preaching about the inherent evilness of a child’s untethered thoughts of sex and death, and he isn’t passing judgment. Instead, he celebrates the impossibility of reaching the bottom of even an everyday mind in the full bloom of active thought. Švankmajer’s film is a great work of surrealism: It invigorates the ordinary and shakes play free of canned sentiment and safety. It’s a monument to the irresolvable, to the unquantifiable vitality of invention.