The history of independent film cannot be written without the name Alex Cox. UCLA-educated but iconoclastic by nature, Cox has never made a light film, preferring to challenge an audience rather than answer to a focus group. While this has earned him scores of admirers, it’s also landed him at odds with the Hollywood system, which turned on him after Straight to Hell and Walker failed to find the commercial “success” of Repo Man and Sid and Nancy. But that was never why Cox worked. Undaunted, he has spent the ensuing decades making films on his terms, as his prior “failures” finally found their audiences and lasting critical acclaim.

Where modern filmmakers look to Cox’s career (and seemingly vice versa, Mr. Cox’s current project, an adaptation of Harry Harrison’s Bill the Galactic Hero, was funded via Kickstarter), Cox found his model in auteur filmmaker/latter-day character actor Dennis Hopper. So it comes as no surprise that, when I wrote about great overlooked soundtracks, Cox pointed out that I had myself overlooked the music Hopper included in his films. “Most young filmgoers think of Dennis as the crazy bad guy from Kevin Costner films,” he wrote. “But he was also an ace director with a great musical sense.” Swords were drawn and blood was spilled on both sides before we ultimately agreed to a phone interview.

As the call turned too good-natured to worry about a serious examination of his or Hopper’s work, what follows is an easy breeze-shooting about Hopper, Orson Welles, independent distribution and the idea that a filmmaker is only as good as his last picture.

Keyframe: We’re here because, when my last article ran, you called me out on my Dennis Hopper ignorance. Quite rightly.

Alex Cox: Oh! About not thinking of Dennis as a director, yes. That’s right.

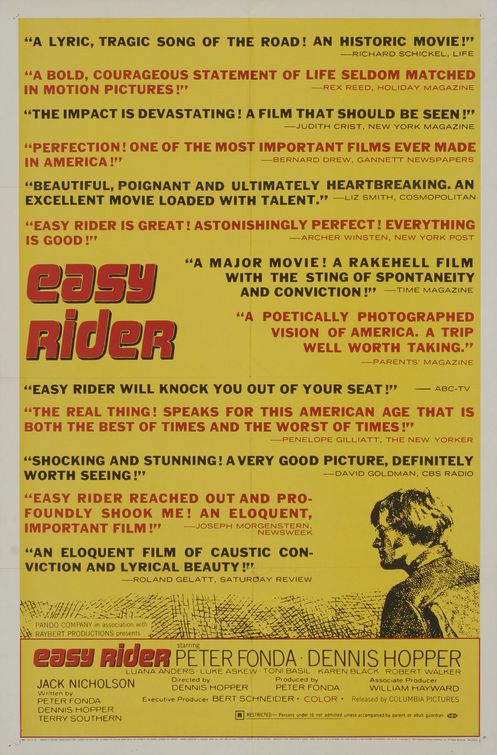

Keyframe: Yeah. I’d actually seen Easy Rider long before I’d realized he’d directed it.

Cox: That’s interesting.

Keyframe: And so, like you said, being a part of a younger generation, I’ve basically only been exposed to him as the psycho from Speed or the psycho from Blue Velvet.

Cox: Yeah, yeah, cause that’s the thing, he’s mainly—for most people he is that, now.

Keyframe: Yeah, he’s generally recognized for his later work that he did—let’s say for money.

Cox: Well, I think he’s always worked for money. He was a director, he was hoping to make money. Easy Rider was such a great payday, because Easy Rider was such a successful film.

Keyframe: To the surprise of everyone.

Cox: Yeah, I don’t think anybody thought it would be as successful as it was. But it was hugely— I mean, I think it got a prize at Cannes, and then it was internationally distributed. Then in the U.S. it got very lucky because the producer was the son of the head of Columbia, and so they got it distributed via the good offices of that guy’s dad.

Keyframe: It’s all who you know, I suppose.

Cox: Oh yeah.

Keyframe: I came to Easy Rider maybe a decade after I’d seen him in Super Mario Bros. as a kid, so my experience of him is generally colored by movies like that. Where did you first encounter his work?

Cox: I think Easy Rider! I think maybe I’d seen him in some cowboy films. In True Grit, probably, where he gets killed and he dies in John Wayne’s arms. So I’d seen him in that, but he was just like a supporting player.

Keyframe: Right, yeah.

Cox: But I hadn’t seen films like The Trip, because The Trip was banned in England. You couldn’t see The Trip over there.

Keyframe: That’s very nice of them. And I understand that you worked with him?

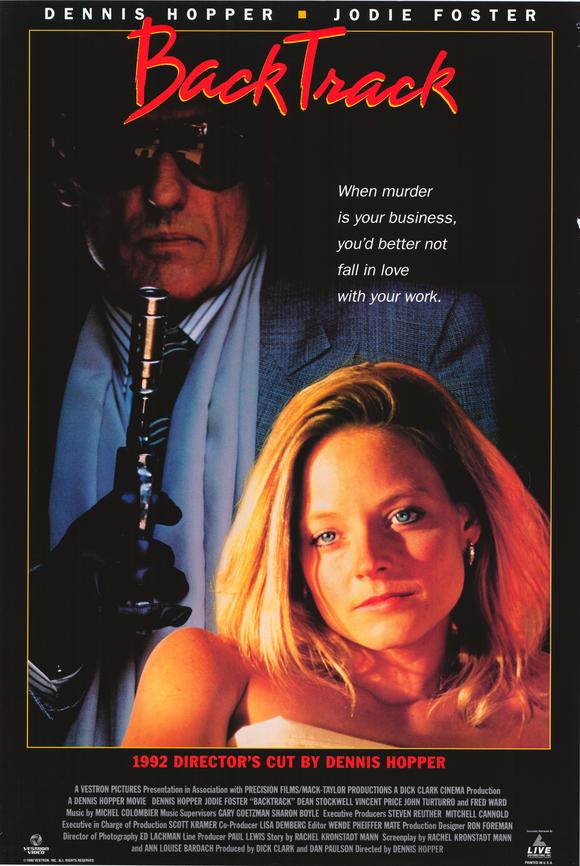

Cox: He was in a film that I made called Straight to Hell, he played the part of I.G. Farben. And I was a writer for him on a film called Backtrack, which he directed.

Keyframe: A.K.A. Catchfire?

Cox: Which is a different version of it, Catchfire is the financier’s re-edited version, and Backtrack is the original version that Dennis cut.

Keyframe: Ah, okay.

Cox: I think.

Keyframe: And is that how you first came to work with him?

Cox: I met him because I wanted him to act in a film I’d directed called Repo Man but we couldn’t make that work. But I liked him, and I thought he seemed like a very nice guy and very simpatico, and so I’d always hoped that I’d be able to work with him.

Keyframe: Who did you want him for in Repo Man?

Cox: The part that Harry Dean Stanton played.

Keyframe: Damn.

Cox: Yeah, Dennis was the guy I asked originally to play that. Harry was second choice, but he was obviously very good, I mean, he was marvelous in it.

Keyframe: Absolutely. Did seeing his career in terms of the projects he directed affect the way you’ve worked?

Cox: I think his early career, because in the beginning of his career he was generating his own projects. The first couple of films he made were films where he found the writer, he came up with the idea, or he and the producer came up with the idea together, and so that was a kind of a template for being a filmmaker. Just like Monte Hellman, a director of that type. He was sort of the hyper-auteurist idea, as opposed to the director who gets given his job, or her job, by the studio. You know, ‘Here, go do this movie.’ And then later in his career, he was doing films that were more mainstream, films for the studio or financier projects where they were just looking for a director so they hired him.

Keyframe: Yeah, work-for-hire stuff.

Cox: Yeah, and Backtrack was one of those.

Keyframe: Of course. Now, how does a filmmaker go from something like Easy Rider to something like Backtrack?

Cox: Years go by, don’t they? Years go by and different opportunities present themselves. I think Dennis regretted not being able to direct more films. I think he really felt his primary work was as a director, rather than as an actor. So he did say that he regretted not having directed more.

Keyframe: Now, when you say ‘directed more,’ would work-for-hire count, or was his regret that he didn’t have his own projects?

Cox: I think a bit of both, because he grew up in the Hollywood system, you know, and he was under contract to Warner Bros., so he saw all these old-time Hollywood directors, George Stevens, Henry Hathaway and stuff, so I think, in a way, he was happy to be work-for-hire. But at the beginning of his career as a director, certainly he was more the ‘author’ director, he was like, it was his idea, he would sit with the screenwriter. So both. I think ideally he would have done both, he would’ve done his own stuff and he would’ve done stuff that he got hired to do, like James Bond movies.

Keyframe: [Laughter.] And, of course, there’s always the work-for-hire that turns into the auteur project, something like Touch of Evil, for example.

Cox: Yes, that’s right!

Keyframe: Which Orson Welles seemed to springboard, if not into Hollywood work, at least into work of his own choosing.

Cox: Yeah, it’s a nice film! It’s a film that he could be very pleased with.

Keyframe: But Orson Welles is also remembered for the wine commercials he did in his later life, unfortunately.

Cox: Well, so what? I mean, he got paid. You have to get money, don’t you? So at least he had a job. The job’s sitting around drinking some wine, that’s not bad.

Keyframe: We’ve all done worse things for money. And so much of Orson Welles’ life seems to have been doing something in the hopes of raising the money to do something he’d actually like.

Cox: Yes, he was always in the process of raising money for the next project.

Keyframe: And it always seemed to be up in the air whether or not that project would actually be completed. It’s a real shame.

Cox: How many films did he leave unfinished? I know The Other Side of the Wind was one.

Keyframe: Yeah, The Other Side of the Wind, I think, is the most complete of the unfinished pictures, but there’s something like—maybe twelve? Lots.

Cox: Wow! Oh wow!

Keyframe: If he had finished every picture he’d worked on, his filmography would double.

Cox: Oh, that’s right, ‘cause there’s a Don Quixote film.

Keyframe: There’s a Don Quixote that Jess Franco did something with. There were a couple of King Lear projects—or no, maybe one King Lear project and a couple of Moby Dicks. And several Isak Dinesen adaptations that fell through.

Cox: How interesting. But after he’d actually shot stuff, is it? ‘Cause lots of people have projects that maybe never got on—

Keyframe: No, yeah.

Cox: He’d actually shoot parts of them?

Keyframe: Yeah. And supposedly his mistress has the reels, the remaining reels of it, in its various states of completion.

Cox: Yeah.

Keyframe: And a lot of the Orson Welles fandom that’s come about has sort of been not just for his completed work, but also for the monuments that he could’ve built, had he been given the money.

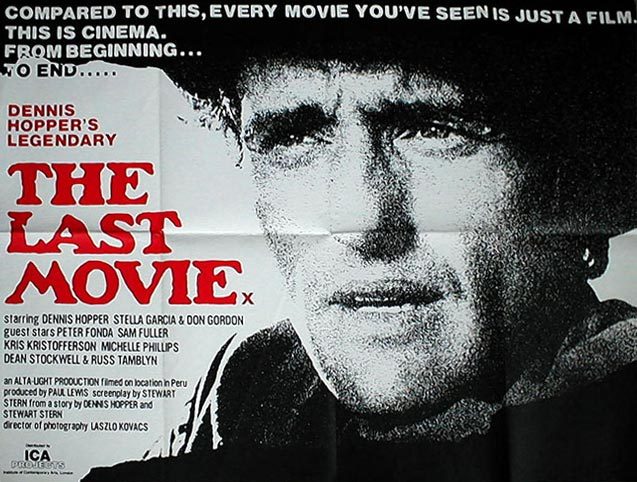

Cox: Well, Dennis—if you see the documentary that is about Dennis Hopper when he was making The Last Movie or he was editing it, there’s a documentary called The American Dreamer, and it’s about Dennis. And at one point, they’re sitting in the screening room looking at the rough cut, or a cut of part of The Last Movie, Dennis is going on this riff about Orson Welles, and about how unjust it was that Orson Welles hadn’t been supported by the studio, or by any studio, since the studios support such low talent, and yet they’d always rejected this great guy and how he was afraid he was gonna end up like Orson. And that’s what came to pass, too!

Keyframe: Tragic, yeah.

Cox: But that’s what happened, too.

Keyframe: Indeed. And we as film-going audiences try to forget that Orson Welles’ last movie was Transformers, the robot cartoon.

Cox: Was he in Transformers? As an actor, right?

Keyframe: Right, yeah.

Cox: Well, that’s different. Being an actor’s okay. I mean, actors are always in terrible disasters and things, it’s—you have to make a living.

Keyframe: Oh, certainly.

Cox: Not their fault.

Keyframe: No, no. And he certainly can’t help that. The expectation that he’d be making nothing but really solid zingers is sort of unrealistic.

Cox: All great, quality stuff, yeah. I mean, actors have to wait for—see, actors can’t generate their own work, or very rarely. That’s why they try and become directors and things because—or why they write screenplays, ‘cause they try to generate work. Because when there’s no work, what does an actor do?

Keyframe: Right.

Cox: It used to be films that were the big thing, but now you’re an actor, a professional actor, what you really want to be doing is episodic television. Play a district attorney, or the fire chief or whatever. And it’s like having a regular job, you know?

Keyframe: Yeah.

Cox: But it’s different from what we think of when we talk about Orson Welles, or we’re talking about Easy Rider. We’re talking about very different aspirations.

Keyframe: Well, there’s always the filmmaker like Welles who, in the quest to find funding, will go down and act in whatever.

Cox: Yeah! Lucky if you can get a job acting, it’s great!

Keyframe: Oh, sure, I mean, it’s good money, it’ll certainly feed you, but you run the risk of warping your legacy in some way. Like how many people remember Erich von Stroheim more for his work than for Sunset Boulevard?

Cox: Oh, that’s right, isn’t it? That’s right. More people have seen Sunset Boulevard, probably. Yes.

Keyframe: Yeah.

Cox: But, then again, it’s a good movie! And he’s very good in it!

Keyframe: [Laughter.] He’s fucking good in it!

Cox: So why not? I think it’s alright.

Keyframe: Right. Perhaps not the best example to use because it happens to be a really good movie.

Cox: It’s a really good film, and he’s in a really good film. So he’s got to be pleased about it.

Keyframe: Sure. But is it important for a filmmaker to try and build up a legacy by keeping away from these projects, or is it unrealistic to expect that this person will only work in artistic pictures or what have you?

Cox: It depends entirely on the personality of the person and the circumstances in which they find themselves. Because somebody’s personal circumstances might oblige them to take a job that they don’t want to do and other people might have the luxury to turn it down. Depends, do they have a family, do they have children, do they have other obligations, do they owe the taxman a lot of money? All these things come into play in why filmmakers do things.

Keyframe: At some point in Hopper’s career it became easy to dismiss him, because he sort of became larger than his own projects. He became Dennis Hopper the Thing, rather than—

Cox: Right about the times of what films, do you think?

Keyframe: I’d say at some point after Easy Rider, even. I mean, I’m not going to lie and say that I’m the world’s Dennis Hopper expert, but it seems to be that everyone’s reaction to him—

Cox: I think because Easy Rider was so sensational in terms of how much money it made, and it was a big youth film, and the studios were all going ‘How do I get a piece of this youth action? How do I make low-budget films for the youth market? How do I do what Roger Corman’s been doing all this time?’ Dennis seemed to have the key to that. That he could do films, but unlike Corman, the films would be treated—at least on the basis of Easy Rider—as serious American art films.

Keyframe: Absolutely.

Cox: And that was what he tried to make with The Last Movie, was a serious American art film. Of course, it wasn’t viewed that way.

Keyframe: It won some award at the Venice Film Festival, it was—

Cox: It won the Critics Award, yeah, but he was hoping for it to be recognized in the US, and of course, that didn’t [happen].

Keyframe: I was talking to some other people about the idea of career rehabilitation for filmmakers and they correctly pointed out that this doesn’t seem to be a problem in Europe.

Cox: Oh, I think it just depends on the circumstances again.

Keyframe: Eh, true.

Cox: Eh.

Keyframe: Because like Claude Chabrol or someone, whose career has never been lightweight, by any argument, but his films have—it’s my understanding that they became less challenging over time.

Cox: Well, that does happen, some people get enshrined and others don’t. I mean, Robert Altman was able to go over to England, and Woody Allen has been able to go over to Europe and make films there, when their careers were kind of grinding to a halt in the U.S. So some people can make that transition. All depends on the circumstances.

Keyframe: Sure. Do you think that, if a filmmaker is seen as something of a washout or a has-been, going to Europe a possibility for career ‘rehabilitation?’

Cox: It used to be, I don’t think it is anymore because of the economic crisis. We always used to be able to get Japanese money for foreign distribution. For a while, Japan was the big supporter of independent film. You could get ten, twenty, maybe even thirty percent of your budget from Japan, and that was a big deal.

Keyframe: Christ.

Cox: So Jim Jarmusch got money from JVC, I got money from Japan, but with the economic crisis, the ability to raise money from foreign sales for independent films has greatly diminished. The Japanese look inwardly now, look to their own independent sector, rather than to ours, the international market.

Keyframe: Has the Internet helped where apparently the Japanese money has dried up?

Cox: Well, the Internet’s great in terms of crowdsourcing, it’s a very positive thing because it’s a form of connecting with patrons to make specific projects, and that’s great. In terms of distribution media, I don’t know how much money you can make from it, because you’re reliant on whoever is supplying the download or the stream. So although it’s great in terms of getting the information, getting the film out there, really what you’re doing is getting the digital information out there in a very small package, so it’s like— compared to actually seeing the movie in a theater, or even watching it on a good DVD or a disc, what you watch on screen on the computer is really kind of picayune by comparison. Unless you have an incredibly fast Internet connection, but then you need a super fast Internet connection to look at a film.

Keyframe: No, of course.

Cox: But it’s good! I mean, as a medium, it’s not helping independent film a great deal. Maybe independent film has to be not monetized, maybe features will end up not being monetized, but they’ll just be done as an art form. It’d be funny.

Keyframe: I think it was Cocteau that said that film can only really flourish as an art form when cameras and film become as cheap as pencil and paper.

Cox: Yeah! And I’m sure he wasn’t worried about distribution either, because why would he care? He got to make the film. He enjoyed it.

Keyframe: Right, his job was done.

Cox: Yeah, that’s the thing. I don’t suppose he worried a lot about people coming to the screenings of Orphée, you know? He was off to a party, or opium or something. Whereas Buñuel is sitting outside the theater, like, biting his fingernails. His life depends on it, he’s got two kids.

Keyframe: [Laughter.]

Cox: So it just depends what their circumstances were.

Keyframe: And you’re at Boulder now, I understand?

Cox: Yes.

Keyframe: Nice! Brakhage taught there.

Cox: Yes, four year gig at Boulder. I’m halfway through it, so I’ve got two years to go. Teaching film production!

Keyframe: And your class shoots a picture in the semester?

Cox: Well, in the past I’ve been teaching production classes where they make short films, like their final graduating short, or intermediate short. This coming semester we’re going to start a project where they make a feature.

Keyframe: Yeah, you’re adapting Bill the Galactic Hero?

Cox: Bill the Galactic Hero, yeah, and that’ll take—

Keyframe: Well done.

Cox: Yeah! And that’ll take like eighteen months. It won’t take quite as long as 2001. Almost.

Keyframe: [Laughter.]

Cox: It’s an interesting situation with these guys, because the university is a university, they don’t want to see the thing get monetized.

Keyframe: Right.

Cox: And my deal with Harry Harrison’s agent and estate is that I don’t pay anybody. It really is an educational experience. So the thing is, I completely—even though it has a budget, it’s also completely divorced from money. There’s no—we’re not really looking at the prospect of trying to get a big distribution at the end, because that’s gonna just complicate things. And we’re not gonna pay anybody! That’s kind of beautiful! We’ve got some money to make the film.

Keyframe: Do you feel like this kind of filmmaking is ideal, when you don’t have to worry about distribution and money and things like that?

Cox: It’s absolutely wonderful, because the only people we’re responsible to are the backers of the Kickstarter. And so what we have to do is make sure each of them receive whatever it is that we’ve signed up to give them, whether it’s a download of the film, or a DVD, or a spacesuit or all those things. Or a robot, whatever it is we’ve promised to give them. The December after next we’re responsible to deliver all that stuff to them. That’s the other thing you’ve got to do, you’ve got to carve out a chunk of the budget to make sure all this stuff gets delivered. So it’s an interesting project, it’ll be very interesting to make the budget with the students. I sort of give it to them and give them some sample budgets and say, ‘You guys figure out how much.’ Because we’ve got all this money, but we’re gonna have to spend it, too.

Keyframe: ‘Here kids, it’s time for adulthood. Here you go.’

Cox: Mm-hm! But devoid of the pressure of personal money. You’re not getting paid personally. It’s still a school project as well, so it’s kind of like Monopoly money, except it’s real.

Keyframe: And this picture will be in your official filmography, as well.

Cox: Absolutely! Absolutely, it’ll be online, it’ll be on DVDs and stuff. We’ll probably just give them out on street corners. It’ll be thoroughly miserable.

Keyframe: How long do you expect to do projects like this?

Cox: I don’t know. I mean, I definitely think, on the basis of this one, that crowdfunding’s a really good way to raise money for films. I mean, probably, if you’re an established filmmaker, you’re gonna have, I imagine, a much better shot at it because people know who you are. And so they believe, therefore, that you’re going to deliver the finished film. But I think it’s just a good way to raise money. It really is.

Keyframe: And you have a readymade audience.

Cox: And you have your audience, because you’ve got—your audience has said that they want to watch this film and so you have to deliver them a copy.

Keyframe: Yeah, they’ve basically already paid for their ticket. All you’ve got to do is make the picture for the premiere.

Cox: That’s right. That’s the plan.