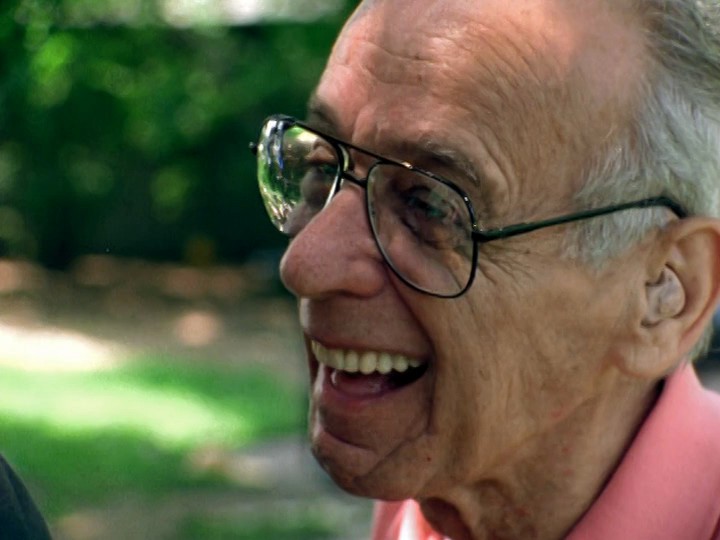

One of the pre-eminent personal documentarians of our time, New York filmmaker Alan Berliner transforms the seemingly ordinary material of his family’s middle-class, American-Jewish history into artfully crafted mirrors that rivet, reflect and refract universal experiences and emotions. His new film, First Cousin Once Removed, winner of the IDFA Award for Best Feature-Length Documentary at the 2012 festival, probes the effects of Alzheimer’s disease on Berliner’s mentor and cousin, the renowned poet and translator Edwin Honig. Simultaneously poetic and tough-minded, First Cousin Once Removed (premiering Sept. 23 on HBO) invites us on an exploration of the real and existential implications of memory loss that marks a natural, albeit discomfiting, progression in Berliner’s gallery of family portraits.

The filmmaker constructed his first long-form effort, The Family Album (1986), from images by and of unknown Americans across the years. His first foray into his family’s checkered mythology, and compendium of regrets, resentments and sticky relationships, Intimate Stranger (1991), is an endlessly surprising and fascinating profile of his maternal grandfather. Berliner then tackled his father in the poignant Nobody’s Business (1996), which uses boxing (not football) as a metaphor and whose pivot point is his parents’ divorce. Turning the camera on himself, Berliner examined the implications and meaning of names in The Sweetest Sound (2001) and the hell of insomnia in Wide Awake (2006).

In our career-spanning conversation, via Skype, Berliner talked about the unplanned career, the necessity of bad ideas, extraordinarily cooperative family members and serendipity.

Keyframe: Let’s begin on a philosophical note. When you started out, the idea of art in documentary was not widely considered. Even today, art is not held as an important element of the personal documentary.

Alan Berliner: The documentary world, for the most part, is very content-oriented. There was a time, even before the transition to high-definition and really good mini-DV cameras, where people were shooting on Hi-8 and other ugly low-resolution formats, and it didn’t matter. It’s the content that matters, the story that matters. That disappointed me for a while, because I’ve always tried to imbue my films with the cinematic. How can I translate my subject into uniquely cinematic terms? What metaphors, with image or sound or sound-image relationships, can I use to make the stories of my films interesting as films as much as possible? That’s been a commitment that I’ve always made. And it’s very rare, to be honest with you, looking back across the decades now, that people pick up on that or acknowledge that. It’s still a very content-oriented discourse. I’m no less committed to making my films as cinematically fresh and dynamic as possible, and to making the storytelling as rich as possible, but the feedback has been consistent for the most part all the way through, which is that it’s about content and subject matter.

Keyframe: What you’re describing strikes me as an American attitude toward documentary. I can think of several European filmmakers whose films, like yours, reveal subtleties and intricacies of structure on multiple viewings. American nonfiction makers may think in terms of three-act structure, but that’s a narrative convention rather than an artistic response to the material.

Berliner: It’s a formula, and I don’t think this is a paint-by-numbers game or process. I don’t believe in formulas. I think each film should generate its own questions, its own answers, its own strategies, its own metaphors and its own inherent language or lexicon.

Keyframe: The structure of your films derives, in part, from your superior gifts as an editor. Did you originally train as an editor? Was that your entrée to filmmaking?

Berliner: No. In fact, I never took an editing course in my life and no one ever taught me how to edit, ever.

Keyframe: I find that astonishing.

Berliner: It’s absolutely true. You have to understand, I have an MFA in Cinema and in my two years of graduate school I didn’t even make a film. I made audio sculptures and video sculptures and paracinema objects—

Keyframe: Installations.

Berliner: Installations, exactly. I didn’t make a film in graduate school. But if I had my druthers, when I got back to New York and I was looking for a job, I guess I would have loved to be a cameraperson. I loved making images. If I had gotten a job as an assistant cameraperson somewhere in the world of making images, probably that would have been my preference at the time. Someone I knew who knew someone who had a connection in the editing world in New York got me an editing job. And the only purpose of getting an editing job, in the end, was that I had access to equipment, at night and on the weekends. I already had my Bolex camera so I didn’t need that, but to have access to Steenbecks and to work with supplies and the tools of 16mm, which were quite cumbersome at the time, that was a big gift. I do remember, in late 1976 in Binghamton, New York, where I studied film, I had shot some material. I don’t even think anyone had taught me how to use the Steenbeck, the flatbed editing table, and I was making a silent film, and I remember for the first time with a 16mm splicer literally chopping the head off a shot and splicing it together. I had made four or five splices and, however fledgling they were, I remember being in a hallway and thinking to myself, ‘I like this. I know how to do this.’ I didn’t quite know what I meant but [I liked] the idea of putting things together. I’ve always been a very organized person with a little obsessive quality. I’m not afraid of details and I’m not afraid of things that may take a long time. And I have an affinity for making connections and associations between things and I always did, even as a little kid. So those are proto-editorial things. Good editors should have a little bit of each of those things in their skill set.

Keyframe: Is editing akin to playing God? You have more control than when you’re shooting.

Berliner: Particularly in the so-called documentary world, editing is where the stories get told. Editing is where you can change the meaning of a shot or the purpose of a shot. Playing God—and I like that expression—you’re in control of the flow of thought. You’re in the driver’s seat of consciousness. That’s a big responsibility but it’s also a tremendous—I don’t want to say opportunity, that’s not the right word—but you’re sculpting the time flow from beginning to end. What people are thinking, and when they’re thinking it.

Keyframe: By what information you divulge, and when.

Berliner: Sure, absolutely. I’ve never written a treatment in my life. I wouldn’t even know how to. I actually wouldn’t want to. For a long time I even resisted the word ‘editing.’ Editing sounds too mundane. I’m inventing the film. I’m discovering the film. I always say that the film starts out with a faint pulse and ends up with a strong personality, and I’m midwifing that along the way. Because in the end, if you’re doing it right, I really believe that the film tells you how it needs to be made, and tells you what to do. At a certain point, forget about producer, director, editor, all that stuff. In the end, I work for the film. The film tells me what to do and I do it.

Keyframe: How did you migrate from video sculptures and installations to documentaries?

Berliner: When I first started out, I didn’t even think of documentary, to be honest with you. I was just making my next film. I was making these collage films, with found footage and found imagery, and suddenly I bought a very large collection of home movies. ‘Wow, that’s a lot of found footage,’ so I made an hour-long film that, for me, was the first foray into content, structured content, that approached the documentary notion. Look at my credits: It says ‘A film by.’ I didn’t know about producing and directing and industry protocol or any of that stuff. I just made the next film. That was the first film I showed at film festivals, so that was a new stretch for me, and a new experience.

Keyframe: This is The Family Album (1986).

Berliner: Yep, turned out to be The Family Album. I have a mythology how I then got to go to Intimate Stranger, which is to say there I am for the first time at film festivals showing my work, and being interviewed by journalists and everyone’s being very gracious about The Family Album, and I’m talking a lot about family and the role of home movies and remembering and what home movies are and how they function in our lives and how they are lies and false representations of reality. And it’s all very interesting, but I’m being treated as if I am an expert in ‘the family.’ And the truth is, I wasn’t. I didn’t think I had the bona fides to be approached in that way. It dawned on me that if you’re going to be considered an expert in ‘the family,’ you should then be an expert in your own family. That’s where it starts. That has to come from inside looking out. I wasn’t a researcher into the family. As it turns out, I had very compelling (laughs) personal reasons to explore my family. And in the end it makes sense, but at the time, the peristalsis of getting to that point was sort of synchronistic and not planned.

Keyframe: You’re referring to the genesis of Intimate Stranger (1991).

Berliner: The Family Album activated a lot of questions about family but it was rather global, if you will—all the footage in the film is anonymous. There were some personal audio elements in the film, but it is essentially an anonymous exploration of American family culture. So now I’m willing to think about my own family, and it just so happened that my grandfather, Joseph Cassuto, my mother’s father, who died in 1974 in the middle of writing his autobiography, had left fifteen large boxes of his papers and his photographs and his whole life in my uncle’s office which had been growing moldy and dusty and no one knew that they were there, no one cared. Wow! This isn’t found footage, although it turned out [there were] home movies, but I’m finding my own family history in this mountain of stuff. And that seemed like a really wonderful, appropriate next film for me. I wasn’t thinking documentary, I wasn’t thinking career, I wasn’t thinking anything except, ‘Whatever’s in these boxes, I’m going to make a film from that material.’ Then one thing leads to the next.

Keyframe: Intimate Stranger had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival, and five years later so did Nobody’s Business.

Berliner: Intimate Stranger is my maternal family history, but Joseph Cassuto is a dead subject, doesn’t say a word in his film. ‘Gee, paternal side—oh, my father. The films will become a diptych.’ I want to say in 1980 I made an eight-minute film called City Edition. It’s all found footage—newsreels, industrials, it’s centered around the New York Times and so forth. I create this surreal section in the film where there are shots of dolphins jumping out of the water and Thomas Edison in his laboratory and scat dancing—a surreal montage. It ultimately becomes a dream. But one of the shots in that montage sequence is a family of four at a kitchen table. It’s as if back in 1980 I had planted a seed to myself, by putting that family of four at the kitchen table, that I was going to have to deal with something at some point in the future. A totally unconscious gesture on my part. I mean, we all plant subconscious seeds to ourselves; that’s a major one of mine. It’s before I made The Family Album. A part of me knew where I was headed before I even—forget about got there, part of me knew where I was headed before I even made the turn down the road, before I even had a compass in my head to know where I was going.

Keyframe: What was your family’s response to these films, specifically seeing themselves on a big screen for the first time?

Berliner: I suppose my first introduction to that shift in scale was when I was working on Intimate Stranger and I had had five and six-hour conversations with each of my mother’s brothers and my mother and everyone knew I was working hard on the film. But no one in my family had a precedent. I didn’t even have a precedent for what I was doing. They had no reason to believe that anything was going to come of it except ‘Alan was being Alan’ or ‘Alan is doing what he does. Let’s indulge him, because at the very least he is—

Keyframe: Collecting oral history.

Berliner: Collecting oral histories about our family and this will be valuable for generations to come. And everyone will participate or collaborate and do what they can. They all knew that I made these weird collage films before this. That was their frame of reference. I don’t begrudge nor do I blame anyone for thinking, ‘OK, Alan will make something because I guess he does that and we’ll watch it in Uncle Al’s living room one day.’ Basically that was the mindset. When I announced to everyone that we were going to have to put the screening in Uncle Al’s living room on hold because we’re going to watch it at Alice Tully Hall in Lincoln Center, the neural network of the family got really activated. (laughs) Went on alert, if you will. ‘Whoa, this is unprecedented. What does this mean?’ It was a big thrill, and I think for at least that side of my family it validated what I did, and they saw that the hard work I put in—well, for everyone in my family especially, it validated the idea that this kind of personal exploration had received its affirmation in broader cultural terms. And frankly, when I then went to my cousins on the Berliner side of the family and said, ‘I’d like to do this and interview you about what it means to be cousins and what is the culture of that side of my family,’ I had the bona fides of having made Intimate Stranger. Everyone was willing to collaborate with me, and go with me, because I had done it for the other side [of the family]. It gave me momentum and it gave me credibility inside the family.

Keyframe: With everyone but your father, whose stubborn defiance set the tone for Nobody’s Business.

Berliner: Well, listen, that’s a complicated case because my father hated Joseph Cassuto and thought that a film about Joseph Cassuto was arguably the most absurd thing that he could ever imagine. Intimate Stranger showed in many festivals around the world and I would tell my father and he would say, ‘People paid? They paid money to see the film?’ Listen, he felt the same way about Nobody’s Business. I’m quick to say that, as funny as it sounds, my father’s position, no matter how arch, is really quite sane. He basically was saying, throughout his life, actually, ‘Listen, Alan, I had my own problems and I wasn’t really paying attention, and somehow when I look back at you, you had become a filmmaker, whatever that means.’ An independent filmmaker, because obviously I wasn’t going to Los Angeles and that wasn’t on the horizon. But my father’s position, which was quite sane and quite logical, is that you make films about subjects that people are interested in. Joseph Cassuto was, my father said, ‘a nothing and a nobody and I wouldn’t give you two cents to see a film about him.’ Well, that same logic applies to the film that I was making about him. ‘It’s ridiculous. I’m just an ordinary, average person. I grew up, I was in the army, I got married, I raised a family, I worked hard, I had my own business, that’s all. That’s nothing to make a picture about,’ as he said. He’s right. But obviously he never got the ironies of what I was doing. And he never understood, nor could he, that I realized early on that my father’s resistance to telling his story reveals more about him, about his character, and in many way about the inherent essence of biography than anything my father might have had to say proactively about his life.

Keyframe: Unlike your father, Edwin Honig isn’t in a position to fight with you because of his Alzeimer’s.

Berliner: My father, you could say, is an anti-hero. I have to explain to him why his life is interesting. Or I have to tell him that any life in interesting. In the case of First Cousin Once Removed, Edwin doesn’t really know his history. I’m showing him photographs, reading him his poems, taking him on a journey through his life and trying to activate memories and responses and create a kind of rich synaptic field within which he might make connections—which he did, to a greater or lesser extent depending on where he was in his metamorphosis. Edwin’s inability to remember teaches us about the role of memory in constructing identity. Edwin’s inability to remember his past shows us the power of memory, shows us how we all time-travel from past through the present into the future. And how, when you can’t do that, you really lose your bearings and you lose a sense of who you are, and you lose a sense of where you stand in the world. I understand that as I’m making the film. Before I put the film together, people think I’m talking to someone who doesn’t remember much about his life or any number of details, but I’m understanding, I’m interpolating, I’m creating a circumstance, a situation, with love, with dignity, with all the power of poetic righteousness I can muster. There’s something more going on here than just the inability to remember. All of my films teach us about the meaning of a life lived, the construction of identity, the role of memory in identity and in the formulation of a life and the formulation of meaning.

Keyframe: The construction of identity is a central theme of The Sweetest Sound (2001).

Berliner: With the exception of Nobody’s Business, there’s always been this impulse to get out of the house, to get out of the kitchen, to jump out the window. In fact, I did it with Edwin, too. Before First Cousin Once Removed, I was going to make a film about a woman who had what the neurologists call superabundant autobiographical memory. I read a scientific paper about a woman who remembered virtually everything about her life. You give her a day, she’ll tell you what she did. She might tell you the weather, she might tell you what was going on in the world in terms of the headlines. The neurologists studied her for five years and she was the real deal. It was an amazing story, and in 2006 I flew out to California to meet her, In my imagination, I’m thinking this is someone basically who must have memory like the Library of Congress has footage. Her memory is like home-movie archives, and I thought that was extraordinary not only in terms of how that works but what that means. What does it mean to have that gift, and understanding that gift might be a curse, too. Anyway, I was starting off in that territory, outside my family, and I met with her and it got a little complicated. I think she got an agent or something. Books and articles were coming out and networks were coming at her. I remember telling her, ‘No one will ask you more interesting questions about what you’re experiencing than I will. No one will take it as seriously. No one will try to go as deep into the implications of what this means, and how memory works and how this connects all the big issues of being human.’ I couldn’t convince her.

And I went to talk to Edwin, because I would do that. ‘Edwin, I got a problem here. I had this whole film planned, or I imagined this film.’ And that’s where things led. Edwin said, ‘It just so happens I think I’m losing my memory, too.’

Keyframe: And that became First Cousin Once Removed. How did The Sweetest Sound come about?

Berliner: I had this idea about making a film about names, and I knew there was going to be this component of inviting the Alan Berliners to dinner. Other than that I thought, ‘Let me go out in the world and make a film that includes 10,000 names—different races, ethnicities, nationalities religions, men, women, maiden names, the whole thing.’ I made a version of that, and it didn’t seem to interest me all that much. I realized, ‘You’re going to make a film about names, guess what? You don’t need to make it about 10,000 names. Make it about one.’ It wasn’t a big stretch as to what name I would use. I thought The Sweetest Sound was, at the time, on many levels a kind of autobiographical film. But for me, Wide Awake, the film that followed, was possibly the most autobiographical film I’ll ever make. I talk about working for the film. That film asked me to do things (laughs) that in retrospect, when I look at it, I can’t believe I actually did. I was completely a servant of the demands of what I thought at the time would make the film work. And it meant going in some personal, delicate territory. I want each film I make to be as challenging and compelling and arguably as difficult as possible, and so they’ve all felt like that. If each film I do, in a different way is the most ‘something’ [laughs] of what I’ll ever do, I’m very happy. I think First Cousin Once Removed, short of me losing my memory one day and chronicling it from the first person, might be as close as I’ll get as a storyteller to the essence of human frailty. It’s a very delicate and, for me, deep and profound place that I went to with Edwin. A very humbling place, actually. In the end, I’m really glad that I went there with him, and that he went there with me.

Keyframe: Humor is an important element in your work, and I’d say The Sweetest Sound required the lightest touch on your part to prick the bubble of self-importance and self-indulgence. After all, if we can ask why Joseph Cassuto deserves a film, then we can also ask why Alan Berliner deserves a film.

Berliner: At the time of The Sweetest Sound, I thought I was learning how to be a film essayist in some way. That’s the first film where I actually spoke out loud and addressed the audience. That’s scary stuff. Particularly when I’d already committed to make a film about names and in the end, my name. Because I had begun The Sweetest Sound with the notion of making it a broader investigation of names, which then turned into a rather in-depth exploration of one name, and that’s where all roads inevitably and inexorably led, the very conceit of doing that is you’re in this narcissistic territory. That was really scary for me, because in essayist terms that’s what’s required of the narrator, because names are tied to ego and identity in ways that are a little embarrassing, for each of us in our own way. I had a screening with the author Phillip Lopate, who’s a good friend and someone who has been very helpful in his advice and wisdom. He’s the master of the written personal essay. He introduced me to the idea that I shouldn’t be afraid. The words I started to write, I was being shy. ‘Don’t hold it against me that I’m making a film about my name.’ He told me, ‘No. You can’t be afraid.’ He noticed the shyness and said, ‘What’s really called for here is a kind of ebullient narcissism. To go in the opposite direction. The audience needs to know that you’re smiling while you’re speaking. That’s part of the conceit of the exploration. That frees you to make certain connections and to say certain things and to make fun of yourself and even to make fun of your name, if necessary.’ That ebullient narcissism and the posturing that comes with that is at the service of trying to get to a deeper place, where names live, inside of our egos, inside of our personalities, inside of our character, inside of us. Let alone what our parents imagined or hoped for when they gave us the names. I struggled with that. I don’t know if I pulled it off. That was a very difficult essay, but I learned a lot.

Keyframe: And the wit and humor that leaks out of your films?

Berliner: I like to think that I have a good sense of humor but I don’t think I’m necessarily a funny person. For me, humor is usually linked, at least in the films that I make, to the acknowledgement and recognition of irony. A viewer understands that something is not what it seems, or something is understood to reflect its opposite. Humor is an audience’s way of telling you that they get something.. My father puts down his grandparents, my great-grandparents, in Nobody’s Business. ‘What do you want me to say? I love them? I don’t give a shit about them. To me, they could have been taken out of a storybook.’ Audiences laugh at that.

Keyframe: Or they laugh at the juxtaposition of the cousins with contradictory opinions of Joseph Cassuto in Intimate Stranger.

Berliner: Right. One of his sons says, ‘I would have much rather been his friend than his son. Because he would do anything for a friend.’ That’s irony. There are big ironies, there are little ironies, but ideally the film is operating on multiple levels, so there are little ironies that find their place within broader and larger ironies. Ideally what’s funny to an audience, the reason that it tickles them is it allows them to reflect on something that they recognize as a truth, or as a contradiction, or as an irony in the way they themselves look at the world, or at the particular relationship to the world that the film is mirroring.

Keyframe: It’s a knowing laugh. They’ve been there.

Berliner: That’s right. They’re laughing because they recognize something true, and usually they recognize something true to their own understanding or their own experience. And family is fraught. Sometimes humor is a release of tension. Because everyone experiences family quite differently. I used to couch everything I said about family in terms of for better and for worse, because for some people family is horrible. It’s boxed them in, it’s not allowed them to be themselves, it’s forced them to think or be or act in a certain way. For some people they can’t get far enough from family. And it’s not funny, it’s not a funny place. It’s a field of contention, and a site of contradiction. It’s easy for people to hate and love at the same time, and humor sometimes breaks through the tension.