The consensus at this point is that Steve McQueen’s 12 Years A Slave is a frontrunner for Oscar glory. No question that this adaptation of Solomon Northup’s account of a free-born African American born living in the North, being kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South, is a film of quite overwhelming power. Bringing what’s been so delicately referred to as “the peculiar institution” into the full light of day, in all its horror, it’s safe to say there’s never been a film quite like it. But that’s not to say it doesn’t have a precedent. It was twenty-nine years ago that famed photographer-turned filmmaker Gordon Parks adapted the same story for television as Solomon Northup’s Odyssey.

Obviously being made for prestige television series “American Playhouse,” Parks’ 1984 film is nowhere near as graphic as McQueen’s. But that by no means lessens its impact—especially in regard to the history of slavery’s representation in the American cinema.

D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, traditionally regarded as a “breakthrough” for filmmaking, was in fact a breakthrough for racism—as it revived the fortunes of a then-fading Ku Klux Klan. In the view of this profoundly specious film, slavery was a necessary protection lest white Southern womanhood be put at the mercy of black men—who of course only had wholesale rape in mind 24/7. There were of course less feverish views that in their own way were almost equally unhelpful. The slaves of 1939’s Gone With the Wind presented as nothing more than faithful servants with nothing on their minds except “Miss Scarlett,” the owner who loves them as if they were her own children. The same brand of condescension can be found in 1946’s Song of the South in which a storytelling slave is little more than a babysitter to white children. As I pointed out in this 2009 L.A. Weekly article the sight of this “family retainer” being “fired” in the film’s near-climax (as his stories have upset the adults who feel his influence isn’t copacetic) is one of the most absurd in all of cinema. But such pretty lies were brushed aside several decades later with 1975’s Mandingo and its 1976 sequel Drum—films in which the brutality of slavery was featured alongside what can only be called “sexploitation” of the sado-masochistic variety.

But it was a far cry from 1977’s Roots, the television mini-series its success made possible. Roots was a thorough humanization of the Africans kidnapped from their native land and brought here as slaves. Its success made Solomon Northup’s Odyssey possible. But again that was twenty-nine years ago. Today, 12 Years A Slave retells the tale in the context of the second term of Barack Obama’s presidency—a time of tumult in which the Republican Party has taken up the mantle once owned by the Southern Democratic “Dixiecrats” opposed to the Civil Rights movement. The triumph of Civil Rights, leading to the election of Obama, hasn’t diminished racist fervor. In fact it’s stoked it as is obvious from this picture taken recently in front of the White House.

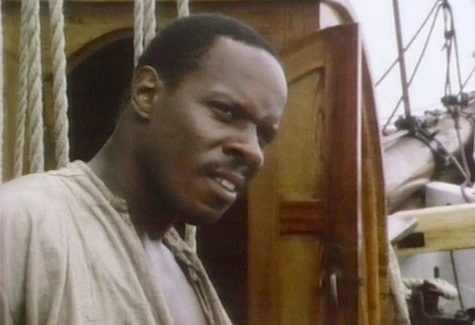

It is for that reason that Solomon Northup’s Odyssey is every bit as necessary to see as 12 Years A Slave. Witten by documentarian Lou Potter and noted playwright Samm-Art Williams (of Frank’s Place fame) Odyssey is directed with enormous restraint by Gordon Parks. It stars Avery Brooks as Solomon Northup. Dignified, often angered and always determined to reverse his ill-fortune he’s a considerable contrast from the ultra-composed Chiwetel Ejiofor, who rightfully seems dazed by what has befallen him and is enormously fearful of what fate holds in store for him. While Ejiofor’s Northup is shown having furtive intercourse with a fellow female slave in silence, Brooks’ Northup has a genuine affair with a slave named Jenny (Rhetta Greene) that humanizes both their characters. Likewise the cruel slave-master Epps as portrayed by John Saxon is more emotionally disturbed than outright psychopathic as Michael Fassbender essays the role in McQueen’s film. While brutal treatment is referred to it is never actually shown. In fact when Epps orders Northup to beat a female slave he fakes the beating by taking her to a woodshed and lashing a pile of logs while she screams as if she were hit. Still this doesn’t make the situation any less disturbing, just not specifically so. The power of scenes involving a woman who goes mad when her children are taken away from her is just as powerful as the ones in 12 Years. In fact, there’s no reason for anyone not familiar with Parks’ version should feel they might “skip it” having “seen it already” in the McQueen. On the contrary. This story of man’s inhumanity to man cannot be told enough or too often. Especially in the last years of Barack Obama’s America.