The first half of the Cannes main competition felt a little…lifeless. But once the festival got going there was no slowing it down. In past years, the jury’s decisions often felt somewhat detached from the general perception of the festival, but this year’s verdict was probably the closest to the journalist’s predictions in quite a while. And there were still some surprises! For example, the best actress and actor prizes were awarded to relative beginners. Samal Yeslyamova of Ayka has only one other film to her credit, Tulpan (Watch now on Fandor), by the same director, Sergey Dvortsevoy. And Marcello Fonte, who took home the prize for Best Actor, has been, until this point, cutting his teeth doing amateur theatre–but his feature film debut in Matteo Garrone’s Dogman is truly spectacular. It’s also worth mentioning that a notable number of competition entries focused on social consciousness and topical struggles, both local and global—from Spike Lee’s BlackKkKlansman to Dvortsevoy’s Ayka to Nadine Labaki’s Capernaum and Hirokazu Kore-EDA’s Shoplifters. Here are our top movies from the second half of Canne’s main competition.

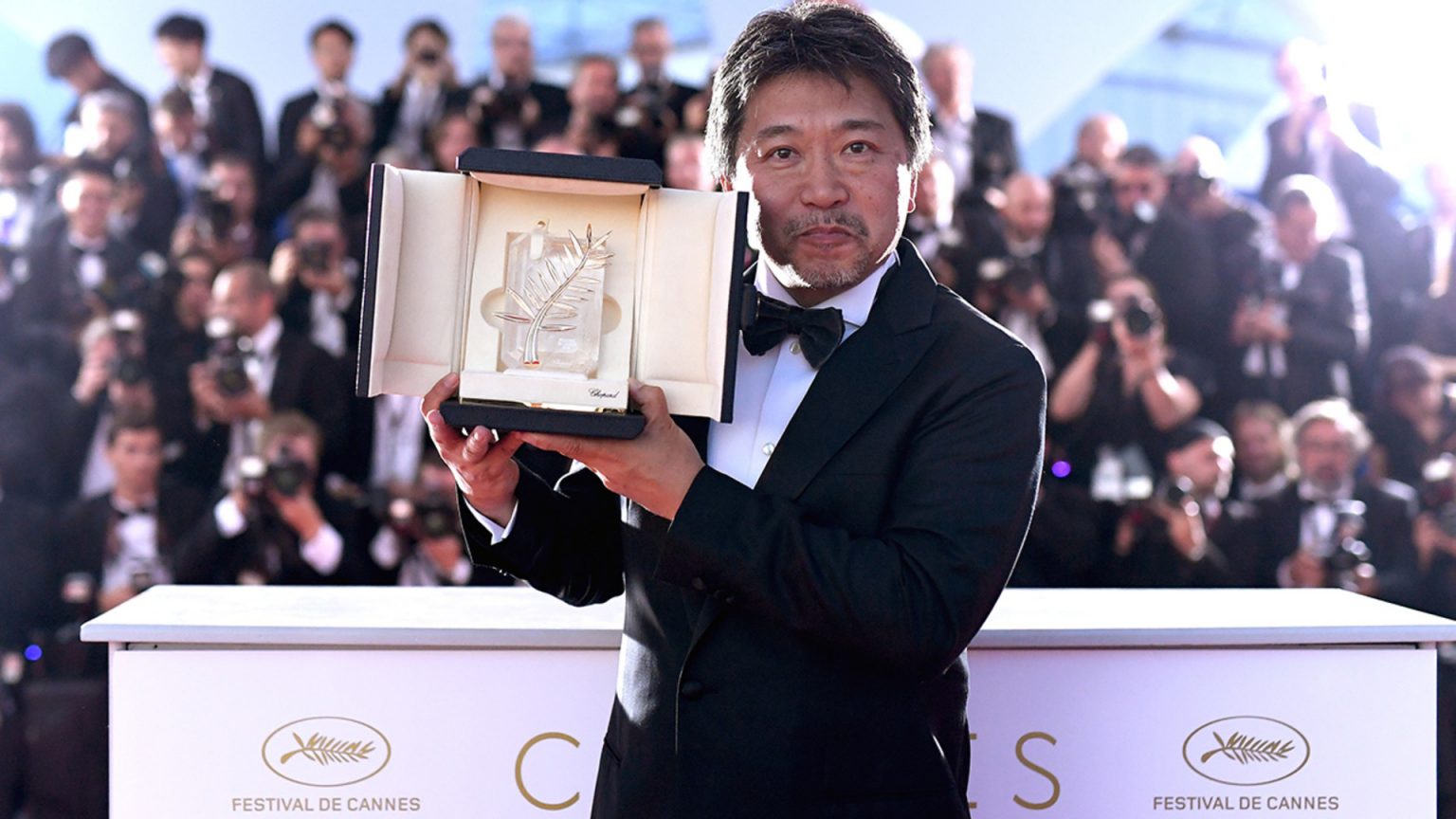

Shoplifters dir. by Hirokazu Kore-Eda, 2018 Palme d’Or Winner

Tatarska: A family of five struggles to get by financially in the Tokyo suburbs. Their bungalow feels as if it is forcibly squeezed in between tenement buildings. Obviously too small for their needs, it is filled with objects, but Kore-EDA’s visuals, slick and tender as always, make it look like a magical kingdom a day before a royal wedding. The social criticism is simmering underneath the film’s seemingly pristine surface. Despite having jobs, the protagonists are forced to shoplift. The nature of their (loving and strong) relationship is put to the test after they take in their neighbor’s neglected daughter and decide to raise her as their own.

It’s the seventh Cannes entry by the notable Japanese director and, in my opinion, the best film he’s ever made. The empathy of the director’s gaze is overwhelming. He never stereotypes his protagonists; he listens to them and allows them to flourish. Touching, but by no means tacky, Shoplifters possesses Kore-EDA’s piercing intelligence and outstanding sensitivity. But this time it also adds physicality and passion. No more taboos! Hurray! A surprising, playful sex scene (oh, the rain!) is probably one of the best movie moments in recent years, in Japan or elsewhere, despite showing no actual sex. I’ve always appreciated Kore-EDA’s talent, but in the past, his work felt almost too “clean,” without a certain needed grittiness, irony or, for the lack of a better word, sex-appeal. In Shoplifters the bucolic atmosphere has been infused with dark humor, sensuality, and bitterness. I love it! Kore-eda has managed to keep his auteur DNA in a film that interprets the tropes of the family bond in a most sophisticated, mature, and simply beautiful way.

BlacKkKlansman dir. by Spike Lee, 2018 Grand Prix Winner

Tatarska: Cate Blanchett called it “a film quintessentially about an American crisis” and she was right, as only Blanchett can be. In Blackkklansman, Lee returned to Cannes’ main competition after twenty-seven years with a story so unbelievable that nobody would ever consider it possible, if not for the fact that it actually happened. It’s the early seventies in Colorado Springs and the local police have hired their first black officer, Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), who embarks on a mission to infiltrate the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, with help of a more experienced (and white) colleague, Flip Zimmermann (Adam Driver). The plot thickens, with Jordan Peele’s support on the producing end.

Lee’s so experienced and skillful that it should come as no surprise that everything from the mounting tension, to the writing, acting, style, pace, soundtrack—I mean everything—is impeccable. It manages to be incredibly dark and equally funny! But the ever-present sense of humor cannot dilute the poisonous hate of the KKK and Lee very intentionally draws comparisons between Donald Trump and his characterization of Grand Wizard, David Duke. And however on-the-nose this comparison might be, it’s an apt and efficient joke. Lee reminds us that segregation and discrimination are not a thing of the past. In 2018 there are still people suffering and dying because of racism. If any young filmmakers are wondering how to make great entertainment without forfeiting the grand idea, watch the movies of Spike Lee. He knows all about it.

Capernaum dir. by Nadine Labaki, Winner of the Jury Prize

Tatarska: What I love about movies is talking about them with people I know. Or with strangers, because movies have that magical power: You start talking about a certain scene with complete stranger, and all of a sudden you’re connecting on a level so deep and engrossing that you only realize later that you forgot to ask their name. But sometimes, very rarely, there are no words to describe how a film has made you feel. This year I experienced that after Nadine Labaki’s Capernaum. In short: it’s a film that reminded me what cinema is for.

In the movie, Zain, a twelve-year-old boy, runs away from home after his parents marry his sister to a much older neighbor. Among the many colorful personalities he meets is Rahil, an Ethiopian refugee, who gives him a home. When she suddenly disappears, Zain is faced with a responsibility much larger than his age. He becomes the guardian of Rahil’s one-year-old son, Yonas. The story is framed by a court sequence, in which Zain sues his parents because they gave him life and therefore made him live in a world in which there is only suffering.

One of only three female directors in the main competition, Labaki has made one of the most disturbing narrative films about the migrant crisis in the last couple of years. The Lebanese director is extremely skillful and possesses a masterful feel for composition, tone, and balance. The casting in Capernaum is extremely worthy of praise. There are no professional actors, just first-timers, whose own lives often intertwine with their character’s dramatic fates. Labaki knows she’s privileged and doesn’t get in the way of her protagonists, whose position she’ll never fully understand. It’s a valuable attitude for the film because no protagonist is judged on first appearances—and some truly evoke instant rage. Another truly outstanding part of the movie is how Labaki portrays girlhood, femininity, and maternity; the movie is full of understanding, tenderness, honesty, and empowerment. Labaki believes film can be a tool for changing the world. Some would say she’s naive. But I hope she’s right.

Under the Silver Lake dir. by David Robert Mitchell

Zaborski: If It Follows and The Myth of the American Sleepover didn’t convince you already, Under the Silver Lake is proof that David Robert Mitchell is a lover of pop culture. Andrew Garfield plays Sam, a thirty-three-year-old Peter Pan, who believes there are secret messages in songs, films, comic books, and even magazines. He lives in L.A., which is full of freaks like him, and every new person he meets gives him another prompt or clue for him to pursue. But the more he uncovers, the more his search is complicated by twists and dead ends. In Under the Silver Lake, Mitchell creates an atmosphere of mystery through a neo-noir style…that also happens to include talking dogs, one-night-stands that suddenly disappear, wild parties, and narcotic trips. It’s very “Lynch-ian,” but Mitchell has his own style and doesn’t copy anyone. He plays with the genre, the mood, and with the audience’s expectations. He reminds us that the movie is not only fun for the viewers, but also for the director. Thanks to that, Under the Silver Lake, is also a love letter to cinema itself, which is built on conspiracy theories, erotic passion, and impossible stories. Mitchell feels its power and shares it with us.

The Wild Pear Tree by dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Zaborski: If you’re in love with Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky, or Yasujirô Ozu, you’re going to fall in love with this film quickly. Nuri Bilge Ceylan uses the same kind of asceticism, minimalism, and frugality, as these great directors. His film is more than three hours long but there is no opportunity for boredom, even though the tale lingers, and there are no sudden twists, nor an air of suspense that could make you hold your breath. The main character is Sinan, magnificently played by Doğu Demirkol, who lives with his parents and sister in Turkey. People around him dream about falling in love, getting married, and having a child, but Sinan is different. He wants to be a writer. He’s chasing his dream, but it is not a career, nor popularity he’s looking for. He’s a literature lover and believes books can change reality. Sinan is a little bit naive and a little bit lost, but at the same time he is full of determination and we know he’s going to achieve his aim no matter what. But Ceylan shows us that to “win” is not about reaching your goal, but how we achieve that goal. With this movie, the Turkish director proves he’s the Chekhov of cinema.

Dogman dir. by Matteo Garrone

Zaborski: Nobody has depicted the lives of gangsters in this way before! In Dogman, Matteo Garrone gets closer to Gomorra, in which he showcased the organized crime problem facing contemporary Italy. Here he also speaks about his fatherland but in a style far from what one might have expected. The script was inspired by a true story that occurred thirty years ago, and that was, at the time, on the cover of every Italian newspaper. The main character is Marcello, a dog groomer and cocaine dealer. He is played by Marcello Fonte, who was honored at Cannes with the best actor award. He really deserved it; his performance is unforgettable. Marcello (the character, not the actor) is one of those “cool guys” who want to be liked and accepted by those around him. Unfortunately, one of those people is Simoncino (another performance by Edoardo Pesce) a “big guy” in the neighborhood who terrorizes those around him. So, you can imagine that there are troubles ahead. But it’s hard to criticize Marcello because he is…adorable. In the opening scene, Marcello is trying to wash a huge, mad dog. With every passing minute, we grow more and more sure that the dog is going to attack Marcello. But when he turns on the dryer and starts to blow-dry the dog’s hair, the dog falls in love with Marcello. And so do we.