Herzog’s 1979 masterpiece still disturbs

In a barren courtyard seemingly untouched by human life, a soldier appears. He’s frantic, running with his rifle. All around him are bleak buildings, their sickly green color nearly matching his washed out uniform. An unnamed authority figure runs alongside him and screams orders. The soldier drops to the ground to do push-ups. His name is Woyzeck. He’s an army barber, low ranking, faceless. For extra money, he’s volunteered to take part in a psychiatric experiment.

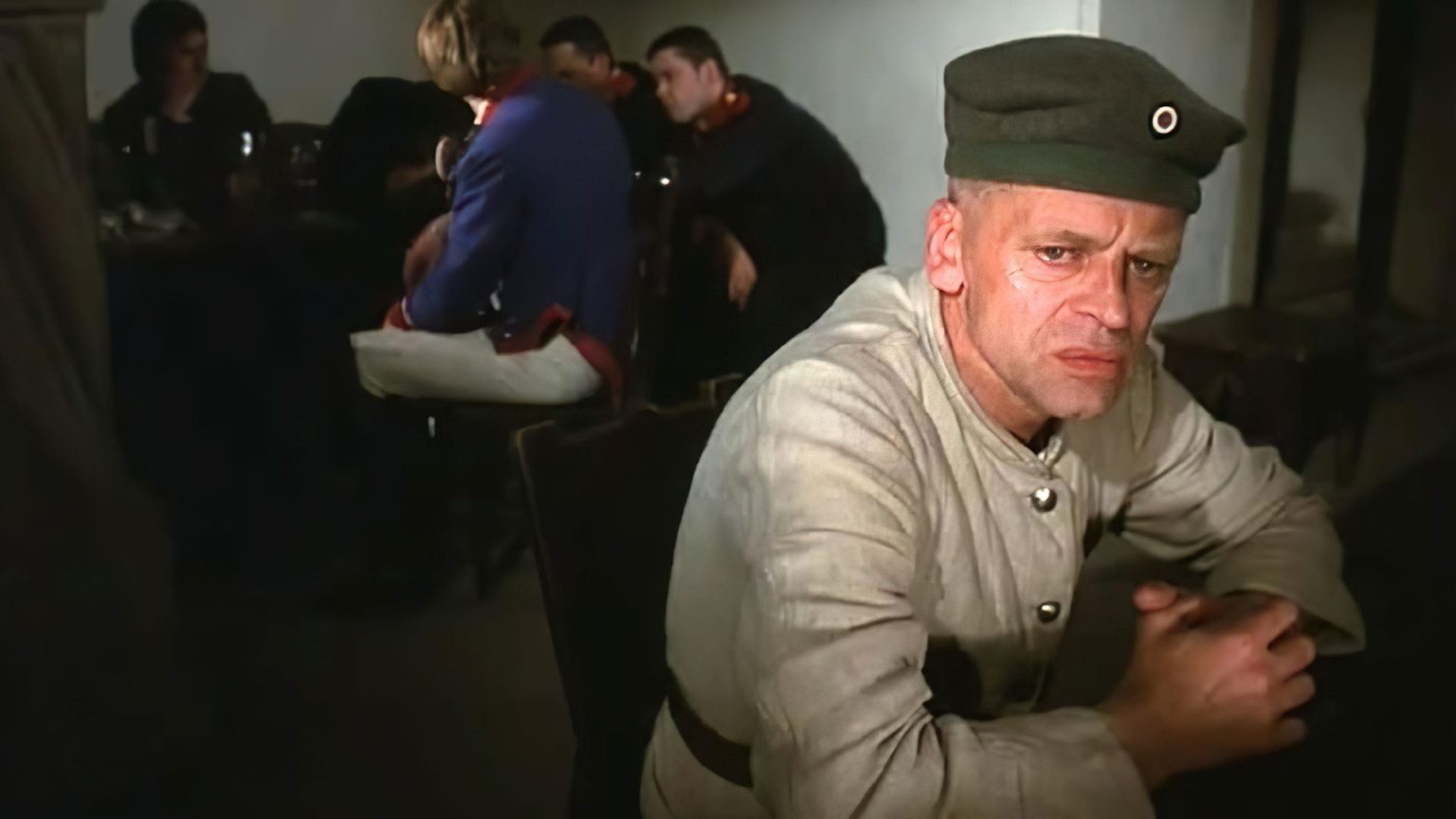

As he performs his mundane exercises, he scowls at the camera. His eyes are filled with hate. Does he hate himself? Does he hate the army? Does he hate us, the viewers?

Klaus Kinski plays Woyzeck, and just the sight of him lets us know things will not go well for this soldier or the people around him. Owning one of the most distinctive faces in the history of cinema, Kinski looks demonic even when he’s portraying a dunce. Married with an infant son, Woyzeck comes home from his duties looking hunched and apologetic, a hobbled husband trying to make ends meet. Under the spell of a local doctor, he’s verging on insanity from the moment we see him; we can’t imagine what this poor man might have been like before.

That is what makes Werner Herzog’s Woyzeck (1979) such a challenging movie. Using Georg Büchner’s unfinished play from 1837 as his source material, Herzog allows Kinski’s bizarre mien to rule the screen. According to an interview Herzog gave to journalist Paul Cronin, Kinski had actually fallen down on the hard cobblestones during the first scene, which caused the side of his face to swell up. Herzog thought fast. He told Kinski, his longtime collaborator and occasional nemesis, “Just look at me.” Kinski obliged. Herzog kept the shot, and used it as the film’s opening.

Woyzeck’s wife Marie (Eve Mattes) is having an affair with a burly soldier she describes as having “the chest of a bull and the paws of a lion.” He’s everything her husband is not. Woyzeck is fragile, demented. The soldier is practically leaking with confidence. When he happily struts for Marie, she looks like she might bite him out of sheer excitement. Marie feels guilty, but she can’t help herself. The scene where Marie dances with this soldier reveals something about unfaithful women; she shows a joy and abandon that she could never show with feeble Woyzeck. She even becomes more beautiful. We watch Marie dance with this man who is not her husband and we almost forgive her.

We know that Woyzeck will learn that his wife loves this other man. The movie’s grim majesty comes from watching Woyzeck make his journey from browbeaten soldier and cuckold to raging avenger.

Woyzeck was made immediately after Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre, where Kinski played the baldheaded monster of the title. In order to save money and take advantage of a Slovakian work permit, Herzog and his crew stayed in Slovakia and started shooting Woyzeck as soon as Kinski had grown some hair. Herzog claimed Kinski had exhausted himself as Nosferatu, which is what helped him seem so vulnerable as Woyzeck. Kinski was often combative with the director in their previous collaborations, but Herzog found Kinski to be very accommodating during the making of Woyzeck. Kinski loved the character and believed Herzog’s vision for the film was important. Herzog had allegedly considered other people for the role, actors more in line with the traditional interpretation of the character, but certainly none as magnetic or otherworldly as Kinski.

It’s a weirdly beautiful movie. Cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein, who had worked with Herzog many times, somehow makes the old buildings and swampy lakes of Moravia look ancient and unhealthy. Kinski is often at the center of the frame, looking every bit as old and mysterious as the failing derelicts surrounding him, as if he’d emerged from a bog. The film’s nightmarish violin score sounds like noise torn from Woyzeck’s own damaged mind. The film’s 27 scenes, each more intense and bizarre than the last, were filmed over a mere 18 days.

Herzog once said, “There is something in the film that is beyond me. It touches the very golden heights of German culture, and because of this the film sparkles.” Kinski is the key. Few actors have ever come so close to capturing the essence of a person unraveling, but Kinski does so in the way he jitters and mumbles, the way he snaps to attention even when he doesn’t have to, the way he hurries down the street with no clear destination. Some might say that Kinski wears the film’s climax on his face, while another actor, Bruno Shultz for instance, would be subtler. They might be right. Still, there’s something spellbinding about an actor whose emotions seem to be writhing under his face. Kinski wasn’t just playing to the cheap seats; he acted as if he wanted to be seen from the heavens.

Büchner’s play is one of the landmarks of German literature. It has been produced countless times for stages around the world, and even adapted for an opera. According to the IMDB, there are over 40 film or television versions of it, the most recent including a 2017 production for British television that transferred the action to Cold War Germany, and a version filmed with Indian actors. A 1972 version from Iran switched the main character from a soldier to a postal worker, long before the term “going postal” came into vogue.

Woyzeck holds a place in German culture similar to the one held in America by Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. But if Death of a Salesman is a mirror of the American way of life, what does Woyzeck say about the German mindset? The two plays, written more than a century apart and on different continents, seem to be related. Both feature an infidelity. One story concerns a lowly salesman; the other a lowly soldier. Both are trying to keep a family together. Both are beaten down by their environments, and overwhelmed by their duties. One story ends in a suicide; the other in a murder. No one wants to be Willy Loman of Salesman, or Woyzeck, but the durability of both plays suggest that these besieged characters must somehow reflect us. Perhaps we watch these stories unfold and think, I may not be exactly like these guys, but I’m not too far away.

In a way, it’s Woyzeck’s jealousy of his wife’s affair that nearly snaps him out of his madness. Of course, it steers him into a new kind of madness, one that involves bloody vengeance, but it’s almost a relief to see him turn into a man of action. Without a cause to fight for, how many of us are just bumbling along like Woyzeck, just waiting for the right humiliation to jolt us into life?