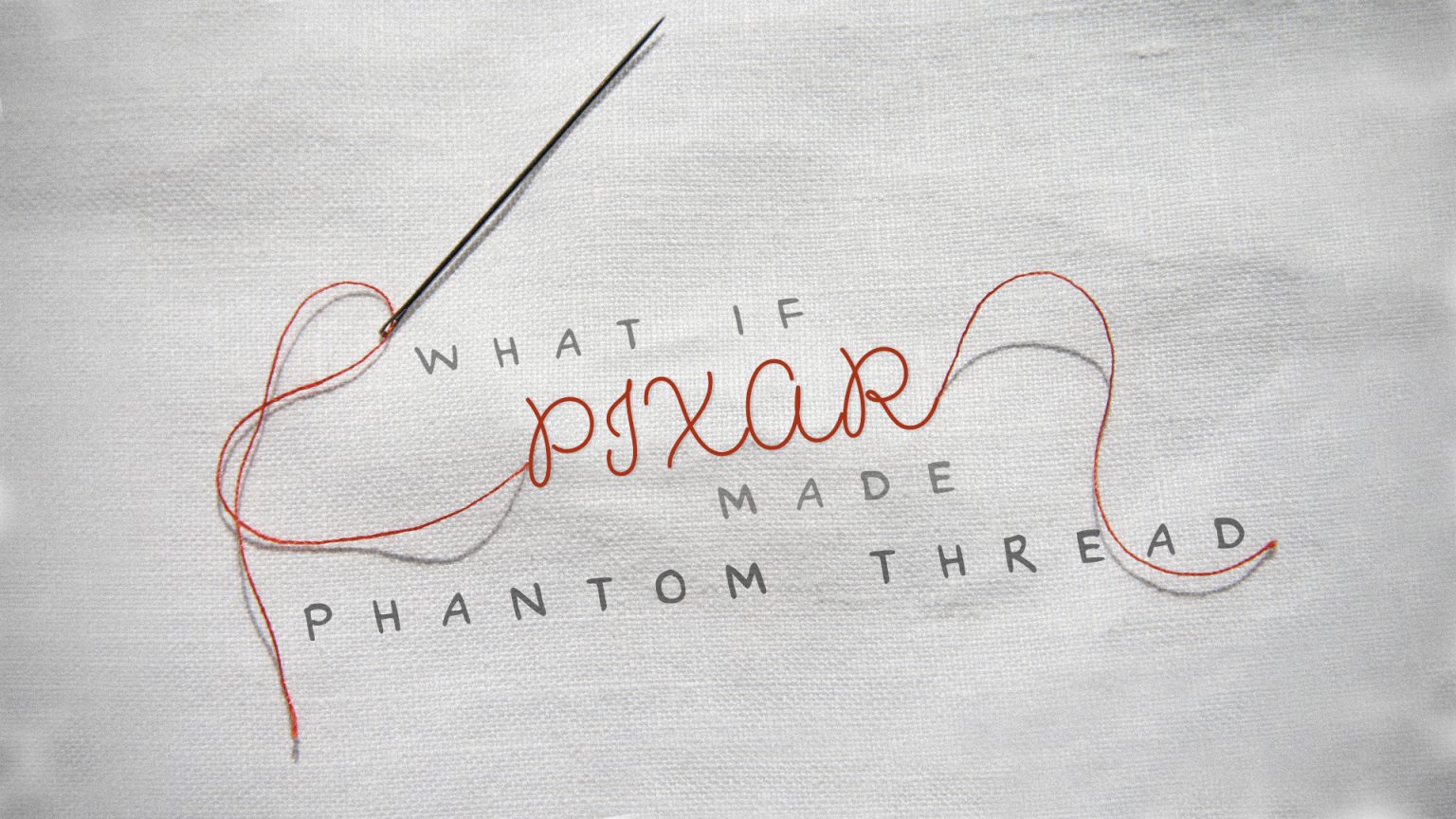

It’s opening night for Pixar’s Phantom Thread. Families with small children make their way into the theatre. The lights go dim and the projector hums to life.

In an alternate reality Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Day-Lewis, Vicky Krieps) doesn’t exist as we know it. Maybe Anderson wrote the script but decided not to make the film. Then, in this alternate reality, Pete Docter, the man responsible for Pixar hits Toy Story, Up, and Inside Out, to name a few, happened upon it and the story resonated with him so much that he decided to turn it into a film of his own: the next animated feature from Pixar.

The scene opens on a 1950s London department store on the brink of closing down. The clothes it sells are out of style. Patrons no longer visit the way they used to, and the poor, clueless owner is downtrodden and distraught.

In this store, though, there is a mannequin, affectionately nicknamed Reynolds by the store owner. After another day of little business, the storeowner dims the lights and closes up, but not before stopping by Reynolds, brushing some dust from his shoulder, and incanting the few words, “If only you could help me. Then, maybe I could make enough new clothes to fill my store.” He leaves, the key twists in the lock, and for a moment all is silent. Then, a stir. Reynolds the Mannequin stretches like a man waking from deep slumber and, all of a sudden, he is alive, imbued with the skills of a master tailor and dressmaker. As he explores his new world, he passes his time taking clothing off of the racks and sewing it into his own unique designs, turning the passé fashions into new and exhilarating designs.

When the store owner returns in the morning he is astounded! His store is full of beautiful clothes. Business picks up and the store is saved. But life quickly grows lonely for Reynolds. He’s the only sentient mannequin among dozens of lifeless others. To quell the sense of isolation, he makes clothes for the other mannequins and, when each outfit is complete, he writes down an imaginary personality for the mannequin and sews it into the linings of the outfits (a young sailor here, a former ballerina there). He imagines himself going on adventures with these “people,” inhabiting their worlds just the way he imagines them to be. This carefully curated life suits him. He gets to control who and what he creates.

Then, one night, a female mannequin arrives. She looks newer, unlike anything Reynolds has seen, and this intrigues him. The next night, to his immense surprise, she too comes to life.

But let’s backtrack for a second.

In the real Phantom Thread, Anderson takes his painstakingly detailed and thoughtful approach to filmmaking and funnels it through the prism of a relationship drama (and, many say, comedy).

The film follows Reynolds Woodcock, a stern, obsessive dressmaker in 1950s London and Alma, the woman who enters his life and becomes his muse. Reynolds always holds the power in their relationship; he’s controlling, and he disrespects her attempts to assert her own identity and express love on her own terms. Alma’s understandable frustration boils over and she poisons Reynolds by stirring toxic wild mushrooms into his morning tea. Reynolds’s ensuing illness lands him in a state of vulnerability, and he abdicates his psychological control to Alma, who cares for him. When he regains his health, he’s a changed man. He realizes how much he loves and needs Alma, and proposes to her. When his love for her starts to dwindle, when he begins to backslide into his old behaviour, she poisons him again. This time, though, Reynolds willingly consumes his mushroom-laden meal because he knows that falling ill again will reignite his love for her and right the ship that is their relationship. Alma implies as much to Reynolds’ doctor, who listens to her, almost slack-jawed, as she explains their strange dynamic, one that must be difficult for anyone else to understand.

This is grown-up stuff, and Anderson has much to say about the nature of adult romantic relationships. Whatever the director’s intentions, whatever “messages” the film conveys, its thematic and conceptual material represent important notions to consider about the nature of love. It’s a bit of a shame, then, that the movie’s adult content is limited to moviegoers of a certain age.

Wouldn’t it be worthwhile to communicate such themes to everyone? How many stories fill young minds with unrealistic fairytale notions of love? Maybe it’s time to make palatable to children some of these more mature ideas. And, who is it that relays adult messages to kids like no other? Pixar.

The company’s storytellers have an uncanny ability to relate grown-up themes to children in compelling, entertaining, and heartfelt ways. Up shows a relationship that begins with true love and end in one partner’s death. Inside Out manages to teach children about the importance of experiencing sadness. Pixar’s Phantom Thread could teach kids about the complicated, unique nature of romantic love.

So, back to the animated film: This new female mannequin has just come to life and mannequin Reynolds is stunned. She calls herself Alma. Though wary at first, Reynolds quickly grows elated over this new and fascinating presence. The adventure the department store together and fall in love.

Problems creep in, though, when Reynolds tries to make her wear his designs. She vehemently resists his attempts to sew her new dresses and costumes, to create his own personas for her. Reynolds grows frustrated with the ways in which Alma disrupts his carefully ordered existence, and Alma grows increasingly upset over the fact that Reynolds refuses to consider her own designs. She has her own identity to explore, and won’t accept one that he makes for her.

She becomes fed up with his pressure, so maybe she slips the owner a note. He doesn’t really need the help, anymore, the message reads. And, for the moment at least, the storeowner agrees. That night, as the lights dim and the store empties, Reynolds does not stir. Now he can’t force outfits upon Alma anymore, and she feels a sense of relief. She goes on her own adventures, makes her own designs. But she really does care for Reynolds (and the store owner again begins the pressure of waning business), so Alma slips him a new message, and that night Reynolds wakes.

This changes Reynolds. He learns to relinquish control and to stop trying to invent an identity for Alma. He lets her become who she wants to be, and he lets her change him in turn. Their adventures become that much more real. She’s just as much in control as he is. He’s not the only storyteller. They collaborate and, as their relationship finds balance, they create an entirely new fashion, something the world has never seen before. Maybe the clothes are so unique that they take the shop’s fame to a new level, saving the poor old owner once and for all. Reynolds and Alma’s hidden work, their “phantom thread,” has saved the store.

Of course, this story needs work. It needs some more meat, some twists and turns, some more whimsical characters, and some more fun—you know, Pixar stuff. Maybe taking a pass through their 22 Rules of Storytelling would help.

The real Phantom Thread manages to convey many sentiments about relationships, ideas that very well may be communicable to kids: relationships are tumultuous, often defined by power dynamics and a constantly swaying pendulum of control. Being in a long-term relationship means having to both maintain and lose control, to pursue and be pursued, to be both strong and vulnerable. Kids really are fine with drama like this, as long as there’s reconciliation. After all, in both the real and the imagined Phantom Thread, Reynolds and Alma remain together.

In the real film, Reynolds’ doctor—perhaps a surrogate for the somewhat stunned audience—doesn’t quite understand the twisted balance that maintains Reynolds and Alma’s love. In the Pixar version, that dismayed old department store owner has little idea where those unique new clothes came from. The crux of the stories isn’t just that they stay together, but rather how they stay together, each in their own distinct ways.

No one is too young to understand love, so why condition children to expect their future couplings to turn out like fairytales, or like any other models? That doesn’t happen, and what really transpires is entirely unique. Maybe it involves poisoning each other, and maybe it involves sewing each other’s clothes. The wonderful thing about real long-term relationships is that each is different in its own way and makes sense only to the people in it. That might be more magical and wondrous than any sort of fairytale romance.

Maybe a movie like this will happen and maybe it won’t, but it’s certainly worth considering. Does anyone know how to get in touch with the folks at Pixar?