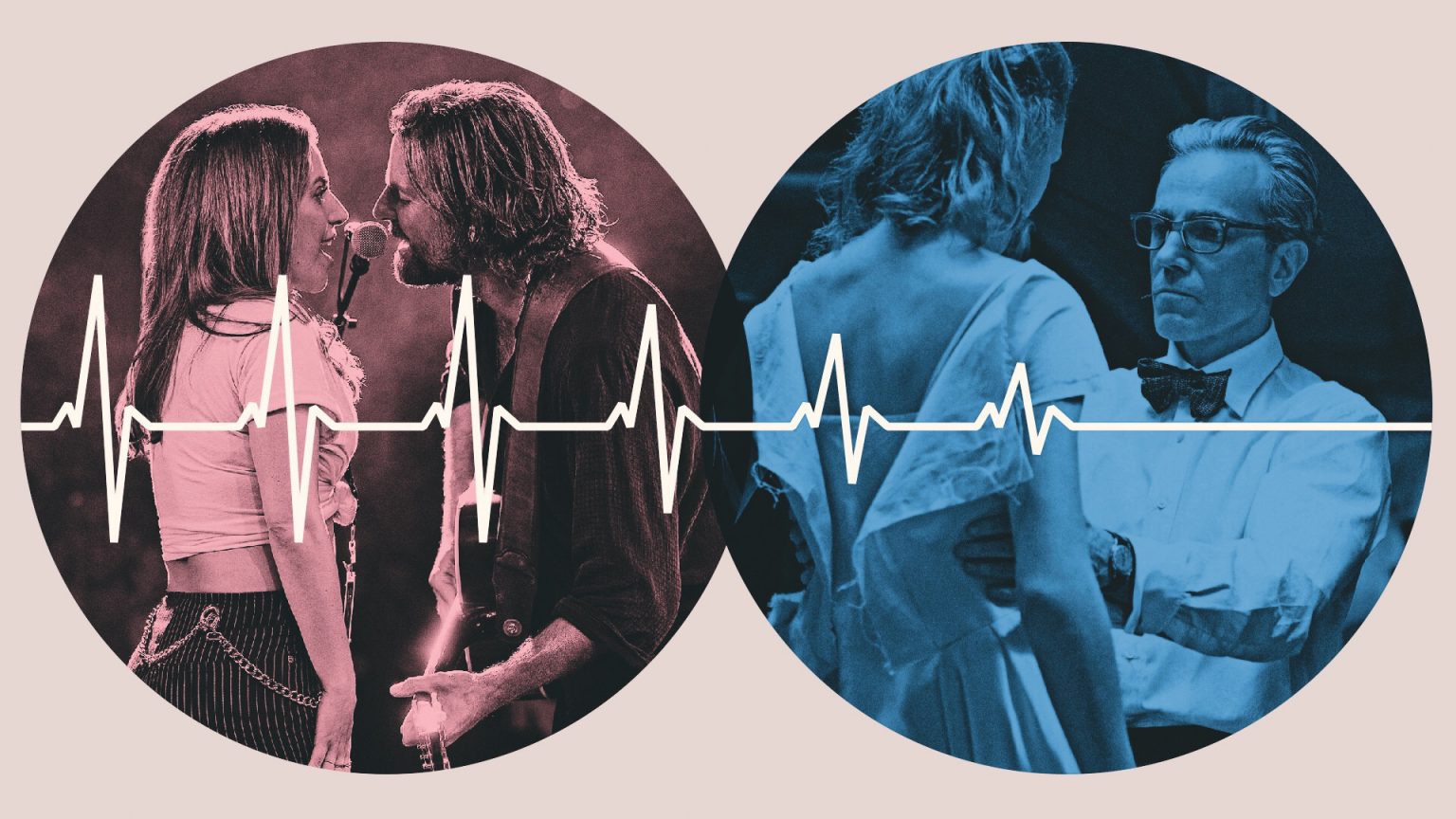

When we look back on 2018, we might see it as the year the mid-budget movie died, or the time they made a Lady Gaga-anthem-sized return. On one hand, Annapurna is standing on shaky ground after an exhausting, tabloid-filled month. And on the other there’s Bradley Cooper’s critically acclaimed and boisterous mid-budget box office success, A Star is Born.

But before diving too far into this subject, let’s define what makes a mid-budget film — and why their continued existence matters to cinema as a whole. While there’s little consensus of the range a film’s budget must fall into to be described as “mid-budget,” it’s safe to assume it’s around twenty-five to seventy-million dollars. And, unlike many blockbusters, mid-budget films are typically more thematically “adult-oriented,” original affairs.

Today, the majority of films fall almost exclusively into two categories: indies (movies made for twenty million or less) or “blockbusters” (movies made for a hundred million or more). However, starting in the late 1960s, with Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde, audiences began flocking in droves to “New Hollywood” films, otherwise known as the “American New Wave.” These films, such as The Godfather, Chinatown, and The Sting represented studio films that played to both young and old audiences, without the extravagant budgets of epics like Ben Hur, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, and even Doctor Dolittle. At the time, filmmakers like John Cassavetes were helping to give birth to American independent filmmaking with movies like Shadows (1958), while many other talented, young filmmakers were ushering in a new era of mid-budget filmmaking that could thrive within the studio system.

It was a beautiful era in cinematic history when foreign titans like Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini could be both Oscar nominees and box office winners alongside filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, William Friedkin, and Roman Polanski — all of whom made films that were deeply personal, intentionally provocative, and thematically mature.

For example, it’s hard to imagine a studio greenlighting a “titillating” title Looking for Mr. Goodbar today, but in 1977 Paramount Pictures, had no problem releasing this Diane Keaton-starrer about a school teacher who embarks on a sexual awakening in order to break the monotony of her everyday life. The movie would not only go on to be nominated for two Oscars, but it was also a financial smash for Paramount, raking in four times what it cost to make. Yet, Goodbar might represent one of the last movies of its era.

In 1975, two years before Goodbar, the film industry was seemingly changed forever by the release of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster masterpiece, Jaws. After Jaws, studios began to believe that everything needed to be a “blockbuster.” It was this thinking that directly led to the rise of the sequel and the prequel, as well as a general increase in budgets (while producing fewer films overall).

Flash forward to 2011 when a little company decided to try to bring back the mid-budget movie by assuring that the majority of their films were original, visionary, auteur-driven projects meant to reignite the spirit of the original American New Wave. This company is Annapurna Pictures, the masterminds behind The Master, Phantom Thread, Zero Dark Thirty, American Hustle, Foxcatcher, The Sisters Brothers, If Beale Street Could Talk, and the upcoming Vice. What do all of these movies have in common? They were all created by award-winning filmmakers on a mid-size budget, and are focused on telling stories that are both adult-oriented, yet completely unafraid to get weird. For crying out loud, Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterpiece, Phantom Thread, is both a perfect portrayal of the ups and downs of love (and toxic masculinity), while also being about how food and illness, including explosive diarrhea, can bring a couple closer together.

Something tells me Disney wouldn’t put even one of their multiple billions of dollars behind a film like this.

Unfortunately, the same may be true for Annapurna. Recently, it was reported that the company is undergoing “financial issues,” which has both created riffs within the company and resulted in the demotion of Megan Ellison, in favor of her billionaire father Larry Ellison — one of the biggest investors behind the company.

To many, this news came as a shock, in large part due to the critical acclaim that the company’s films have received, as well as the awards-worthy titles they plan to release in 2018. If Annapurna can’t keep the mid-budgets alive, then who can?

That’s where A Star is Born comes in. A true studio film — albeit one that has been remade three times — Bradley Cooper’s directorial debut cost roughly forty million to produce. Because of the film’s mid-range budget, Cooper was able to convince Warner Bros. to allow him to make a personal and deeply empathetic story. Unlike an indie film, the movie’s mid-range budget allowed Cooper to add a layer of studio polish to the final cut, which included excellent production values, beautiful cinematography, and hummable original music. Yet there’s also a grittiness and a “go-for-broke” emotionality imbued into the film that is rarely seen in studio titles these days.

And, despite the general Hollywood ethos that believes solely in blockbuster movies, A Star is Born performed like a blockbuster at the box office, while also garnering significant critical approval.

Nonetheless, while A Star is Born, and arguably Gone Girl and American Sniper from a few years ago, prove that some mid-budget films can appeal to people across demographics, it’s worth remembering the overall reduction in the number of “original” films that don’t rely on an already existing intellectual property. For the mid-budget film to truly return, we need studios to embrace and champion original stories and characters. And with Annapurna potentially going through a major change and no other company yet stepping up to produce and distribute original films as they have, it’s hard to say if 2018 was the return of, or the beginning of the end (again) for, mid-budget films.