Like other media critics, I’ve taken a fascination with Apple’s popular holiday ad “Misunderstood” that features a socially withdrawn, seemingly maladjusted millennial using his iPhone to get him through a family holiday, only to reveal to his relatives what heart-warming objective he and his digital companion had been up to all along. Part of what makes the commercial so unsettling is that it is so accurate—look around at just about any public event or private gathering, and it’s clear that one’s experience of it is increasingly being supplanted by the desire to document it. In other words, one mode of reality has replaced the other, which leads to the question: when there is so much attention being paid to the representation of reality, how does this transform the initial experience of reality (will it even remain “initial?”) much less our grasp of what is real in itself? Especially when things like the Apple ad are actively encouraging us to trust its technology to show us how we should best experience our most intimate moments among friends and family?

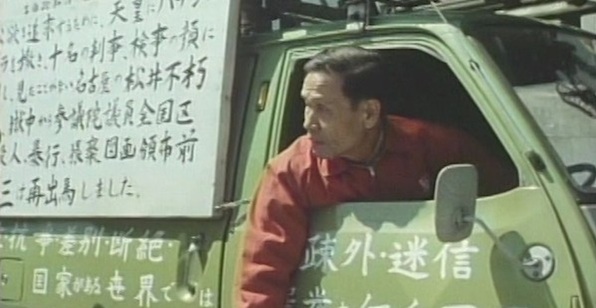

The Apple ad makes for a stark contrast with a landmark documentary by Kazuo Hara, The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On. In this searing, one-of a kind work of radical investigation, Hara follows sixty-two-year-old Kenzo Okuzaki, a Japanese WWII veteran turned recalcitrant activist, seeking to unmask the unspoken atrocities committed during the war by his nation, specifically acts of murder and cannibalism committed by his fellow soldiers. His odyssey comes to a head during the Japanese New Year, when he pays a visit to Yamada, an ex-soldier who may have witnessed and participated in the cannibalism of a comrade while stationed in the jungles of New Guinea in the waning days of the war.

Other than presenting a very different kind of holiday gathering than the Apple ad’s, the scene directly confronts the issue of what is real and how the real is represented. Yamada lives in an advanced state of denial, emodying a national state of amnesia as he prefers to forget the horrors of the past in order to live at peace in the present. He has even written a memoir about his war experiences, but lets on that he avoids mentioning the full extent of what he experienced, so as not to disturb the memory of the dead. Okuzaki counters that his omission of the unpleasant details is precisely what dishonors their memory because it distorts the facts. It’s a distortion that has weighed on Okuzaki’s conscience since the war and has informed his own unhappy existence, the shocking details of which he relates with unnerving frankness. The scene is a stunning collision of two kinds of personal truths reflecting two kinds of realities: the reality that we prefer vs. the one that we are afraid actually is.

As a response to the Apple ad, I’ve taken this scene and popped it into Apple’s iMovie software to see what kind of holiday video could be made of it. Since the Apple ad is more or less an instructional video for how to better enjoy one’s holidays, I’ve also turned my Kazuo Hara video into a “how to” video for holding a radical holiday party. I know that this kind of move might potentially be seen as disrespectful towards Hara’s incredible work of filmmaking as well as the sensitive subject matter it explores, but I can only hope that these acts of irreverence point to the larger question of “how” we are expected to relate to our experiences, the pleasures we strive for and the unpleasant realities we prefer to avoid—what role we assign the tools and technologies that give shape to our realities, if we really want them to speak on our behalf.

Kevin B. Lee is a filmmaker, critic, video essayist, and founding editor of Keyframe. He tweets as @alsolikelife.