Measuring films in calendar years and hierarchical lists feels a bit like ranking friends or, worse, rating relationships (Noah Baumbach’s Zagat history of a former romance rather drolly makes the point)—even if the impulse to canonize serves us well historically. And Godard did it. Now receding from view, 2013 may not have been revelatory in the vintage sense, but increasingly the cinema landscape feels like a terrain to be inhabited and traversed, paused in and coursed over. There are epiphanies and lulls, to be experienced in turn, contingent upon the curiosity of the imaginatively agile wanderer. At the very least, film years should me measured against Hong Sang-Soo’s given output. A few associative notes from the trip, then….as 2014 brings us the “awards season” to remind us where we’ve been.

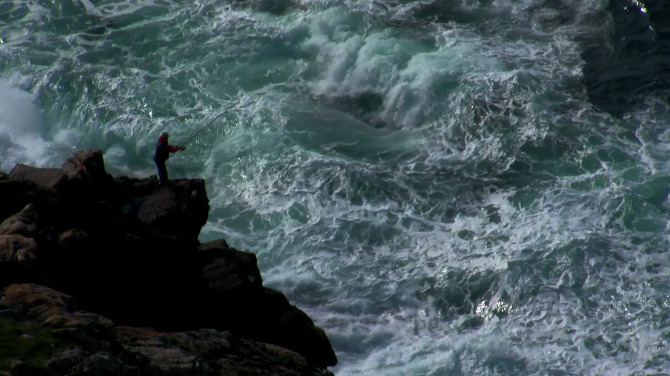

In April, at the Buenos Aires Independent Film Festival, sunk into the labyrinth of the infamous Teatro San Martin, Galego filmmaker Lois Patiño apologizes for the projection image quality of a work-in-progress entitled Costa Da Morte (Coast of Death) which he’s presenting along with some fine shorts that evince a young director working in a formal capacity—the long shot—in spectacular fashion. There is a visual splendor recalling Burtynsky, while the intimacy of the eavesdropping sound channels Galician fishermen’s folk tales of shipwrecks and daily catches. Epic and intimate, but never overbearing, this portrait of a community in the finis-terrae is scarcely morbid; it teems with life and resilience, most palpably evidenced by a memorable shot of percebes harvesters ducking fearlessly beneath the crashing sea foam, clinging to the rocky outcroppings. It’s the kind of unforced sequence that could continue for hours and still be offhandedly hypnotic, much like the film itself. The full-length film was finished in time to premier at the Locarno Film Festival, where Patiño unapologetically won the Best Emerging Director Award. It would go on to play the New York Film Festival, a true coup for Patiño, who studied in New York before completing his masters at Barcelona’s famed Pompeu Fabra program.

There’s something worth paying attention to on this side of the Iberian peninsula, from the strange Galician tide including Vikingland (Xurxo Chirro), Arraianos (Eloy Enciso), The Fifth Gospel of Gaspar Hauser (Alberto Gracia) and the production company Zeitun, headed up by Martin Pawley alongside Oliver Laxe and Felipe Lage, responsible for the film Todos vós sodes capitáns. While the Portuguese continue to astonish: Miguel Gomes‘ Redemption is an historically expansive found-footage (short) film that, by employing a prolix voiceover intoned by an illustrious cast of directors, reconfigures history in deceptively conceptual but crushingly sincere ways. As does Joaquim Pinto’s and Nuno Leonel’s The New Testament of Jesus Christ According to John, in which the gospel is delivered by actor Luis Miguel Cintra accompanied by shots of landscape that possibly express such divinity (or mercifully leave as an unimposed possibility). Coupled with the magnum opus What Now? Remind Me, it is clearly Pinto’s year. João Pedro Rodrigues is too prodigious to be considered marginal: both Mahjong (directed with João Rui Guerra da Mata) and The King’s Body are playful conceptions in genre that will someday speak to the career cliché of “early Rodrigues” just as early Almodovar remains his most trenchant work. Gonçalo Tocha followed the success of It’s the Earth Not the Moon with a work in a similar vein, this time devoted to the rare female skippers of a fleet of fishing boats in Vila Chã on the Portuguese coast. Part history lesson, part soliloquy to the sea, part homage to the bravery of women, The Mother and the Sea is reflexive documentary that’s both salty and modest in its inquiry.

To the sea! Coast of Death, The Mother and the Sea, and Leviathan all made for a seafaring year in film while offering unique ethnographies unto themselves. The brutal beauty of Leviathan was a source of considerable debate, as if it were an object to be loved or loathed, rather than immersed in experientially; a film yoked to the real while conjuring a gossamer optic plane that suggests Brakhage imagining Herman Melville. The SEL continued its run as the most compelling source of documentary filmmaking practice, with Manakamana being the examplary case: Spray and Velez have made a formally beguiling account of Nepalese cable cars gliding to and from temple, with passengers caught somewhere between stupefaction and boredom—both legitimately conducive states for the work of worship in an increasingly modernized world.

The structural documentary found unprecedented expression in James Benning’s haunting (in the non-hyperbolic sense) Stemple Pass. It’s technically a 2012 film, but I saw it this year and can’t get it out of my system, its clumsy incantation of Ted Kaczynski’s lucid delusion of modernized America set to four seasonal shots of his hermetic cabin (a replica fashioned by Benning), ensconsed in the shifting landscape, constitutes the slow-burning fomentation of violence as it moves between imaginary and actual realms.

An unlikely bridge between Benning’s corrosive pastoral and Richard Linklater‘s Peloponnese talky anti-romance, Before Midnight, could be located in Gabe Klinger’s satisfyingly improbable study of the two directors, Double Play. The juxtaposition is illuminating rather than gratuitous toward a consideration of durational elements in film, and offers the possibility that Linklater may be more experimental, and Benning more pop, than we’re inclined to think. Auteurist vulgarity could yet be an untapped descriptor. As a side note, was it possible to view Before Midnight without succumbing to the gravitational hole occasioned by Ariane Labed’s luminous cameo as Anna? Her brief turn does not go unnoticed by Hawke’s Jesse, nor Linklater’s mise, and hints at a discreet Greek influence of Yorgos Lanthimos and Rachel Tsangari (who plays Ariadni as well as produces).

No heroics, please: the best bit of acting was more an ephemeral flash of grace, as Romina Paula (Ruth) hops into the back seat of a car in Matias Piñeiro’s Viola in what appears to be a dream sequence. She figuratively and literally appears to have stepped in from another dimension, so candidly unassuming is her presence. And Viola is built around such unsuspecting moments: the spritzing of potted plants never seemed so cinematic in retrospect. Also from Argentina, Los Posibles is Santiago Mitre’s unexpected “dance film,” a propulsively choreographed (by Juan Onofri Barbato) piece of physical theatre that transfigures social work into an abstracted West Side Story; young men from Gonzalez Catan forging an industrial space into an emotionally fraught arena, scored to a punishing drum score. It’s nothing like Mitre’s political drama and better for it.

Lastly, Mati Diop‘s doc-fantasia Milles Soleils mines the legacy of her uncle’s 1972 Senagalese classic Touki Bouki, focusing on the present-day life of its lead, Magaye Niang, a cattle herder who’s lost some of his swagger, wandering Dakar unrecognized: he haggles with a cab driver and turns up late to a public screening of Mambèty’s film, while dreaming of his co-star who’s fled to Alaska. Compact but suggesting layers of intertwined history, it’s certain to illuminate— however many shots of rum—Diop as foremost a director to define the future.