A seamstress’s daughter hops off a streetcar in Moscow, crossing the railroad tracks toward home. Three gunmen wearing dusters kill time on a railway platform in Flagstone. Under the lounge car of a commuter train, a stranger accidentally knocks shoes with another stranger. Meanwhile, a bleached blonde schemer lies in wait for the 9 o’clock from San Francisco, her husband dead in the back seat. Elsewhere, the Doppler effect on the soundtrack raises chill bumps as an engine roars into a tunnel—ahead a captive might be tied to the tracks, or maybe, a desperate outcast waits for sweet release.

Tracks and switches moving apace under the camera, cramped coach corridors pressing new lovers into a first embrace, steam whistles blow plaintively in the distance or ear-piercingly close. With only the slightest visual or aural clue, we know if there’s trouble ahead and of what kind. The track stretches before us or behind us. We’re moving on, we’re trapped. Or—time simply passes, something banal or breathtaking on view in the aspect-ratio window. Sometimes a symbol of modernity, nostalgia or doom, sometimes a crucible for love, fear or no-good, trains have proliferated in the motion pictures as settings, plot devices and metaphors since that first locomotive pulled into La Ciotat station.

Go West

A year after John Ford’s epic The Iron Horse about the glories and sacrifices of building the transcontinental railroad was America’s top-grossing film, Buster Keaton produced this gem about going west as an epic act of humiliation. A committed gearhead, Keaton disassembled and reassembled an entire motion picture camera the night before his first day on the job with Fatty Arbuckle’s production company. His love of cameras (and what they could do) might be matched only by his love of trains, which he often used in his stunts. In The Electric House, dinner’s soup course arrives from the kitchen onboard a model train. Sherlock Jr. features an extended bit with Keaton trying to walk off a moving train and ends with him getting doused under the water tower spout. The General, named for the locomotive that Keaton’s character commandeers during the Civil War, is the de facto costar of the film for which Keaton blew up a train trestle and sent a locomotive careening into the river below. In Go West, Keaton’s train stunts are less showy but no less inventive, or hilarious. Broke and alone (his character’s name is Friendless), he stows away in a freight car full of wooden barrels. When one threatens to roll him out the open cargo door, he seeks safety on a heap of them. He’s jostled about, the heap collapses and he gets trapped inside one of the barrels, then he’s rolled off the moving train anyway. The train was a staple in westerns and had been at least since the payroll box tempted the cowboy bandits in Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery. More revisionist westerns like Keaton’s were to come, from Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West through Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, the railroad playing its questionable part.

La roue

A hard-drinking company man, Sisif rescues a young girl from a train wreck that opens the movie and keeps her for his own. She grows up loving the railyard where they live, proudly donning the conductor cap while playing “All Aboard!” His older son, on the other hand, has nothing but disdain for it, fantasizing about an idealized past when a horse was as fast as you could go and time was kept strictly by the sun. A prolific peddler of cinematic metaphors, Abel Gance achieved an astonishing realism by shooting La roue at the massive classification yards in Nice. “Every member of the company is in constant danger from the incessant passage of trains,” someone on the scene said of the shoot. “A watchman keeps constant lookout and rings a heavy bell every time a ‘Hundred Tonner’ bears down.” This danger and tension of the location shoot is palpable onscreen as Sisif goes half mad with incestuous thoughts and tries to use his locomotive to commit suicide. An astonishing catalog of film technique, superimpositions (the engineer’s face over the locomotive as it heads straight for us down the track) and virtuoso camera angles (mounted on the wheels of the train), the film stood out for its rapid cutting style that served Gance’s overriding metaphor (roue is French for “wheel”). Whether the wheels of the train incessantly roll or a traditional circle dance celebrates the coming of winter, La roue’s characters spin at destiny’s whim. One intertitle quoting Kipling’s Kim drives the point home: “Pity it is that these and such as these could not be freed from the wheel of things.” Adding historical poignancy to the story’s fatalism, Gance’s wife Ida was ill throughout production and despite the director’s willingness to rewrite the film on the spot to accommodate her health (mid-narrative, Sisif is transferred to a funicular in the purer air of the Alps), she died as soon as the film was completed.

Il ferroviere

Alcohol and train conducting often mix to tragic ends in the movies. Jean Renoir’s La bête humaine is based on the same Émile Zola murder mystery involving a homicidal engineer, a jealous station master, and his wife that was the source material for Fritz Lang’s later Human Desire. But Gance seems to have told the whole story of railway men in one eloquent scene in La roue when the camera tracks round the company store taking in the worn-out faces of the men, just before a drunken brawl breaks out. By the time the neorealists arrived to depict the postwar working class, such fates seem to have changed little. In Pietro Germi’s portrait of one engineer’s family, the modern world is personified by defiant children and changing roles for women; the railroad is what’s old-fashioned. It’s Christmas Eve and the family waits at home for the paterfamilias. However, Marcocci, who had once helped the Partisans overturn a train during World War II, prefers the warm glow of the neighborhood bar. Even the pleas of his adoring young son—strongly reminiscent of the steadfast Bruno from Bicycle Thieves— can’t drown out the tavern’s beckoning accordion song. It’s one of many waylays the young Sandro won’t be able to prevent. The other Marcocci children flout the old ways, as the father struggles to hold onto them. When his alcoholism costs him his job, he crosses a picket line to pay the bills, losing the respect of his comrades. The film’s opening scene presages the changes to come. Shot with a camera on the front of the locomotive, we are hurtling into the station. Suddenly, a switch is thrown, shifting the ground under our feet, now headed in a new direction with no letup in speed.

Alois Nebel

After World War II, trains took on a menacing new sheen. With deportations to death camps and gulags, the mechanical became truly monstrous. A lengthy, largely wordless sequence from David Lean’s Dr. Zhivago telegraphs the uncertainty and anxiety of those forced train trips to Siberia. Jirí Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains ends with a young station agent in wartime Czechoslovakia leaping heroically onto the top of a freight car, carrying a small, lethal box. The 2011 animated film Alois Nebel centers on another Czechoslovakian railway agent. He spends years bound to the station, witnessing the nefarious uses of the railroad by both the Nazis and Russians. To soothe his mind, he recites the station stops and times. Now that the Soviet Union has collapsed and the Russians are withdrawing—doing more damage before they do—Nebel can no longer suppress the ghosts of his own past that seem to return with each arrival of a train. In one spectacular scene, Nebel is sitting at his dinner table when a memory is triggered of his mother leaving. Things begin to rattle as the house windows transform into coach windows, and the camera rushes backward until we’re clattering full bore down the railroad tracks. The rich black-and-white palette of the drawings lend a gritty atmosphere while the Rotoscoping of the characters produce an overall unease. Nebel’s quietly uttered schedules become a substitute litany for the dead or missing, and his unreliable reality a paradigm for life under a police state.

Wendy and Lucy

The sounds of a moving train cue audiences to mood changes or plot points. In Some Like It Hot, Billy Wilder evokes era and mood when the Florida Ltd. pulls out of Chicago to the jazzy rhythms of the Society Syncopaters. Preston Sturges cuts to loud hilarious whistle bursts as Henry Fonda reacts to his bride’s inventory of past lovers on their wedding night in Lady Eve. The lonesome whistling blowing is a much more common device and may have passed the point of salvageable cliché. When Jason Schwartzman wishes aloud for the sound of a passing train after a particularly poignant moment among the brothers in The Darjeeling Limited, he gets a resounding chorus of “no’s” instead. The best filmmakers still have found fresh uses for the noises of the railroad. Dr. Zhivago’s second half begins with a dark screen (70mm’s worth) with only the train on the soundtrack, returning us to the anxiety inside the crowded freight cars. J.P. Sniadecki’s The Iron Ministry, an exploration of class differences in China, begins in the same way but to different effect: the darkness an opportunity for viewers to unload expectations. In Wendy and Lucy, Kelly Reichardt’s screen adaptation of the short story “Train Chorus” is about a down-on-her-luck woman trying to realize the dream of the open road and its promise of a better life. Already low on money, her car breaks down in Oregon and her dog Lucy goes missing. It feels like the end of the line. Like the railroad and its ambiguous promise of elsewheres for the skid row castoffs in Lionel Rogosin’s On the Bowery or for Apu and his luckless sister in Pather Panchali, Reichardt’s train is barely there, yet still exerts a power. The film opens on the cars collecting in the Portland station. Later, looking for her dog, Wendy lingers a bit on the tracks, watching them as they disappear into the forest around the bend. Diffused whistles of arriving trains or the muffled roll of another departure lightly pepper the soundscape. It’s not alarming, nor promising, just a quiet possibility.

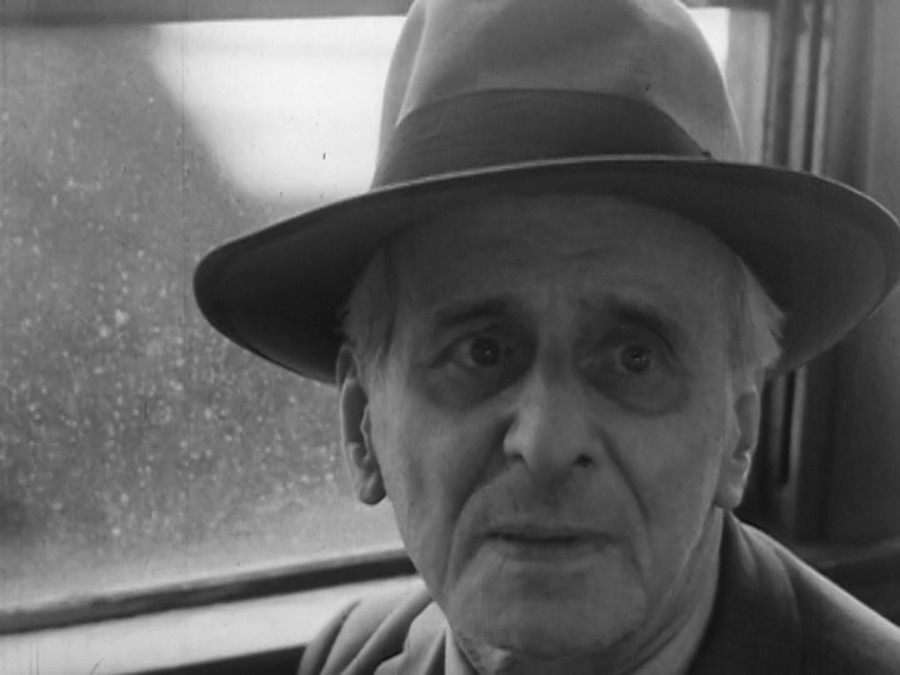

The D Train

While the actualities of early cinema made a spectacle of excursions and their destinations, one enterprising exhibitor married the idea of train travel with moviegoing in 1905, opening Hale’s Tours, ersatz railway carriages outfitted with movie screens to share the view. The silent-era Soviets conceived of trains as mobile film labs and theaters to spread the revolution to the vast hinterlands and, for filmmakers like Dziga Vertov, the train was a steaming gleaming pistons-roaring iron-incarnate of progress. Experimental filmmakers have continued to play with metaphors of the railroad, mining its close relationship to cinema. Jean Mitry’s Pacific 231 is cut to Arthur Honneger’s eponymous orchestral work inspired by the song of the steam engine. Polish filmmaker Marcel Lozinski’s 89mm from Europe is an eleven-minute observational masterpiece about converting western European trains to the wider gauge in the Soviet bloc on trips east. Guy Maddin’s Odilon Redon submerges a steam engine into an underwater world awash with surrealist allusions. Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil equates riding the train to moviegoing, both a kind of public dreamstate (or maybe delusion). Jay Rosenblatt’s The D Train is a found-footage Hale’s Tour of one man’s life, spanning the short distance from the playgrounds of carefree childhood to the park bench of old age. Set to the waltzing violins of Shostakovich’s Jazz Suite #2, the kinetic collage circumscribes a lifetime into a series of movements—a crawling baby, a twirling carnival ride, rubbing early morning eyes, crossing an intersection, reaching out to pat someone’s hand—little gestures and great strides that accumulate into a flash-before-your-eyes remembrance you wish had no end.