This was an unusual year for avant-garde cinema, at least in terms of its presentation in North America. In New York, the shift from “Views from the Avant-Garde” to “Projections” meant a programming committee, as opposed to the very strong curatorial personality of the departed Mark McElhatten. The Projections group—Aily Nash, Dennis Lim, and Gavin Smith (who was McElhatten’s old programming partner for Views)—made some significant changes, most notably eliminating the overlapping screenings that had made it increasingly impossible to take everything in. Some new names graced the program, although not all of them were particularly welcome. There’s something to be said for an “old guard,” after all. They can light a shot, edit, move a camera and end a film when it ought to end.

Over in Toronto, “Wavelengths” keeps expanding, while paradoxically having less and less time to screen experimental short works. Such is the growth pattern at TIFF, where bigger is always better, and some unseen administrator is always chasing the Almighty Loonie. Most confusingly, TIFF decided to apply its new premiere rules (world or North American premiere, or no show) to Wavelengths, so any underground trifle that reared its head for a millisecond in Ann Arbor or Windsor was now ineligible. This resulted in some dodgy, second-rate inclusions dotted among the gems.

But overall, this has been what we might call a maintenance year. Good filmmakers produced solid films, as is their wont. The major new experimentalists who emerged, almost en masse, about five or six years ago, are now settling into their acclaim and their working methods. A few new voices made themselves known, but not many. And even those filmmakers whose works have been hovering on the precipice of greatness for a while simply continued to hover. Interestingly enough, this overall tendency toward steady quality, and perhaps inadvertent burnishing of the brand, is mirrored by much of this year’s output in auteurist narrative cinema. Great directors like Cronenberg, Trier, Assayas, Andersons P.T. and Wes, and even Pedro Costa to some extent, made very fine examples of “their kind of film,” but didn’t break substantially new ground.

Granted, that’s not what an artist has to do every time he or she steps up to the plate. But even if we’ve long since abandoned those quaint ideas of the avant-garde as a constant revolution, the bellwether for aesthetic and cultural change (Forward, Soviet!), it is notable when we seem to be slowing down and reflecting a general comfort with what ought to be disruptive procedures. If experimental film becomes a genre, it won’t be one with much of a following. “In which of the seven designated ways will you ‘surprise’ me this time?” I can’t see it holding up.

Even if innovation was in short supply, it was hardly absent. My top five films from this year all displayed something new. In some cases that something new was a way of organizing image and sound material that departed from shopworn avant-garde maneuvers; in other cases it was a posture or an attitude with regard to structure or representation, a refusal to adhere to established concepts of what experimental film looks like. Almost all of them expand the more time you spend with them. A few resemble documentary but are actually meticulously constructed. Others seem more overtly political than others, until those subtler works reveal their relationships of image, identity, and form, engaging in social and political discourse by other means.

Episode of the Sea (Lonnie van Brummelen, Siebren de Haan, and the inhabitants of Urk) (Toronto: Wavelengths; CPX:DOX; IDFA)

At once the strangest and the most familiar film I saw in 2014, Episode of the Sea is an experimental documentary featurette about the island of Urk and its citizens’ traditional methods of commercial fishing. Presented in stark, sharp black and white that resembles Garrel by way of Vigo, the film includes the subjects themselves as nonprofessional performers telling their story and demonstrating their trade in a stilted, arrhythmic manner. They are less Bressonian models than jovial Kaurismäki figures, far more comfortable with labor than with language. In penetrating fixed-frame stares, van Brummelen and de Haan show us the Urkers on their fishing boats, casting the nets and hauling them in. Such a film might seem redundant, a mere two years after Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s Leviathan. But instead, Episode is like an answer-film, covering much the same territory with a wholly different set of emphases. The two “weird fishing movies” are fully complementary, and both are masterworks.

Sound That (Kevin Jerome Everson) (Toronto: Wavelengths; New York: Projections; London: BFI)

This year I had the great fortune to really delve into Everson’s cinema, seeing around fifteen films within a weekend. This is usually the best way to gain a more nuanced understanding of a filmmaker, even though it’s not always possible. Imbibing Everson’s work in relative isolation, rather than seeing a film here or there in the middle of group programs, I felt like his project finally clicked for me. There is frequently a surface level engagement that Everson’s films can fool us into settling for, an offhanded, vernacular style that inattentive viewers may mistake for social documentary. This is partly because of racism. The history of African American cinematic representation cues white viewers to expect something anthropological, and this is a spurious bias Everson shrewdly exploits. This interpretive schema is as hopeless as trying to watch Brakhage for the narrative.

Once we get past this category error, Everson’s actual artistry becomes readily apparent. Not only are most of his “street scenes” staged or directed in some way. They have underlying formal structures that condition the social material, creating internal comparisons and repetitions. Sound That is a brilliant example of this. Made with a group of workers from the Cleveland Water Department, the film observes the painstaking procedure by which faults in the subterranean infrastructure are located and repaired. Using metal rods and hammers, the men engage in deep listening to hear probable leaks resonating up through the asphalt. (The work is real, but Everson coordinated with the city employees to decide where in town they would film.) We observe the team’s collaborative spirit and their care in assessing, once and for all, where they’d have to tear up the street and begin the next phase of the project. Sound That shows collective effort, trial and error, and in its emphasis on cutting, patching, and the distinction between sound and sight, serves as a perfect metaphor for the filmmaking process itself.

The Innocents (Jean-Paul Kelly) (Toronto: Wavelengths; New York: Projections)

At this point, Canada’s Jean-Paul Kelly is the most consistently surprising experimental filmmaker on the scene. His recent work shows points of contact with his broader efforts as a multimedia artist (photography, graphic arts, drawing) while asserting itself as specific to the medium of cinema. That’s to say, Kelly’s films stand as utterly independent while evincing the richness one finds in artworks borne from conceptual connections explored in other media. Kelly has been making experimental films and videos for nearly a decade, but those of us south of the border were a little slow on the uptake. Highly enigmatic, bearing textures rife with self-contradiction—wood grain and vellum, found still images and the wispy pocks of film in the gate—Kelly’s work echoes Philip Guston, John Baldessari, and especially Robert Gober, while never feeling less than sui generis.

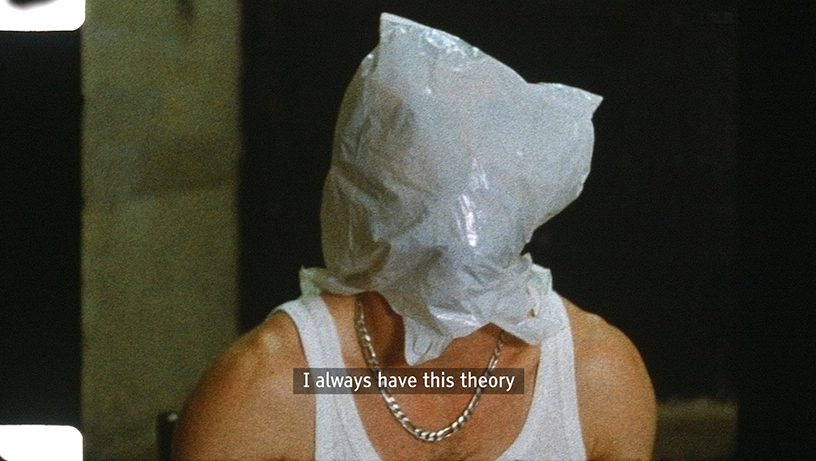

Following the outstanding Service of the Goods (a study of proxemics and performative values in the cinema of Fred Wiseman, starring homemade white-sheet ghosts), Kelly has produced another film that operates according to his essential signature while expanding that vocabulary to consider different, unexpected themes. The Innocents borrows its central text from an interview with Truman Capote, in which his stand-in (a young man in a T-shirt with a drink and a plastic bag over his head) explains his method of reporting as a kind of dialectic between active desire and utter detachment from the subject. As a counterpoint, we see Kelly introduce a series of photographic images onto a piece of plywood. Each has a prominent hole in it, its torn or ripped edge distinguished by a primary color. The images start out as rooms, then shift to become bodies, both dead and alive, engaged in official politics and sexual acts. The holes are disarmingly polyvalent, implying bullet holes, sexual orifices, as well as purely decorative perforations. The Innocents is a bracing work that displays, with a vague but palpable tension, the slight shift by which an image can be turned against itself.

Shoot (Gaspar Noé) (Online: “Short Plays” Project, Univision Deportes)

The money to get films made can come from anywhere these days, and if you’re particularly invested in the careers of particular makers, you need to keep your eyes open. Artists seem to find all sorts of unusual ways to get short films out into the world. This year, a number of other international directors (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Carlos Reygadas, Fernando Eimbcke, Pablo Stoll, Vincent Gallo) were commissioned by Univision to make short films to be bundled with the network’s online coverage of the 2014 World Cup. The only stipulations of the assignment were that the films had to represent their nation, and be about futbol in some way. The “Short Plays” project received surprisingly little attention from the film community at large. This may have to do with a fatigue with such projects. It was only last year that the Venice Film Festival gave us the massive “Future Reloaded” series, celebrating the fest’s seventieth anniversary with seventy short films, one each from virtually every major filmmaker still currently living. Did anyone plow through them all? Similarly, the document-dump of all these World Cup films (most of which were in fact mini-narratives involving soccer) on a website that isn’t a customary destination for cinephiles, meant that a great deal of effort mostly went ignored.

Sadly, this meant that most viewers missed Gaspar Noé’s finest film since Irreversible, and quite possibly his best work to date. The five-minute film, Shoot, takes place in a dusty vacant lot situated between banlieue blocks in moderate disrepair. The ground and the walls are a sunbaked yellow; the sky is a dense blue streaked with well-defined clouds. Noé uses his allotted time to show us a friendly pick-up game among a group of Arab and African teens. We’re to understand that this is their neighborhood, and we’ve been invited to play. However, we aren’t in the game as players. Noé’s experimental camera placement puts us in the 360° point of view of the soccer ball. We roll and fly, the ground and the sky whirling in an unanchored sphere of vision, our only points of reference being the kids who will happily kick us again. Noé knows his avant-garde, of course; Shoot is a sly riff on Michael Snow’s La Région Centrale. But where Snow’s film placed us in the middle of nowhere (frozen, desolate Quebec), Noé situates us in the heart of modern France. It is changing, and traditional points of reference will no longer hold.

Hacked Circuit (Deborah Stratman) (Sundance; Ann Arbor; True/False; AFI; Rotterdam)

Much like my encounter with Everson’s films this year, 2014 was the breakthrough moment when I felt myself fully connect with Stratman’s work. With previous films of hers, such as In Order Not to Be Here and O’er the Land, I gathered that I understood their intellectual project, and admired them for their efforts. But Hacked Circuit possesses a sensuousness and a sly wit that won me over completely. In this film, Stratman is interrogating the political ramifications of the senses, the problem of whether or not we can trust the reality laid before us. While the movies are the controlling metaphor for this inquiry, Circuit’s implications are clearly much broader.

In a single nighttime Steadicam shot, we slowly ease around the side of a building on a nondescript L.A. corner. We eventually hear noises coming from the building—speech, loud crashes, and a general clatter. As we round the corner and enter the open doorway, Stratman shows us that we are exploring a sound studio where Foley artists are at work. That is, we first hear what seems to be a realistic, coherent envelope of noises, only to discover that they are being produced by one man in order to accompany the actions that exist in another diegetic realm (on a screen behind him). Suitably enough, the Foley artist and engineer are doing sound work for Coppola‘s The Conversation, the classic film about sonic surveillance and paranoia. As Gene Hackman tears up his apartment floor looking for bugs or other high-tech sonic spy devices, the man in the studio crunches planks of wood to create the plausible sound for the film. Stratman allows us to watch the Foley work for a while, and then the unbroken tracking shot wends its way back into the studio’s back room, filled with all sorts of random junk which we are now asked to examine differently—for what kind of sound it could make, if used “improperly.” As the camera exits the studio through the back door and goes back onto the L.A. street, sounds become diegetic (“normal”) again, but we have no reason to trust the film Stratman is showing us, at least in terms of the faithful marriage of sound and image. How do we know that this apparent synchronicity isn’t a technical fiction? In the end credits, we hear Hackman again, this time from Enemy of the State, frantically explaining that our mobile phones have allowed entities like the NSA to track our every move through satellite surveillance. Hacked Circuit then ends with a dedication to the great film editor and sound engineer Walter Murch and NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. Hacked Circuit combines formal and ethical questions to pose a challenge to its viewers: what paradigms have you dislodged today? As it happens, this has become one of art’s biggest conundrums in a very messy, deeply troubling 2014.