There is no shortage of troubling news these days, with the United States at war abroad, mired in several geopolitical conflicts while, domestically, the country remains divided over a number of serious, often controversial issues that hold major consequences for countless lives. It’s no surprise that protests and other political and cultural responses abound. But when problems don’t seem to change, we inevitably question the merit and efficacy of political activism, and of idealism in general. In the face of a relentless onslaught of challenges, one can’t help wondering whether an individual can really enact the kind of change that they wish to see in the world, or if cynicism, apathy, and resignation will prevail. If the 2006 documentary The U.S. vs. John Lennon is any optimistic indication, one person can, indeed, make a difference—but the lesson might not be what you expect.

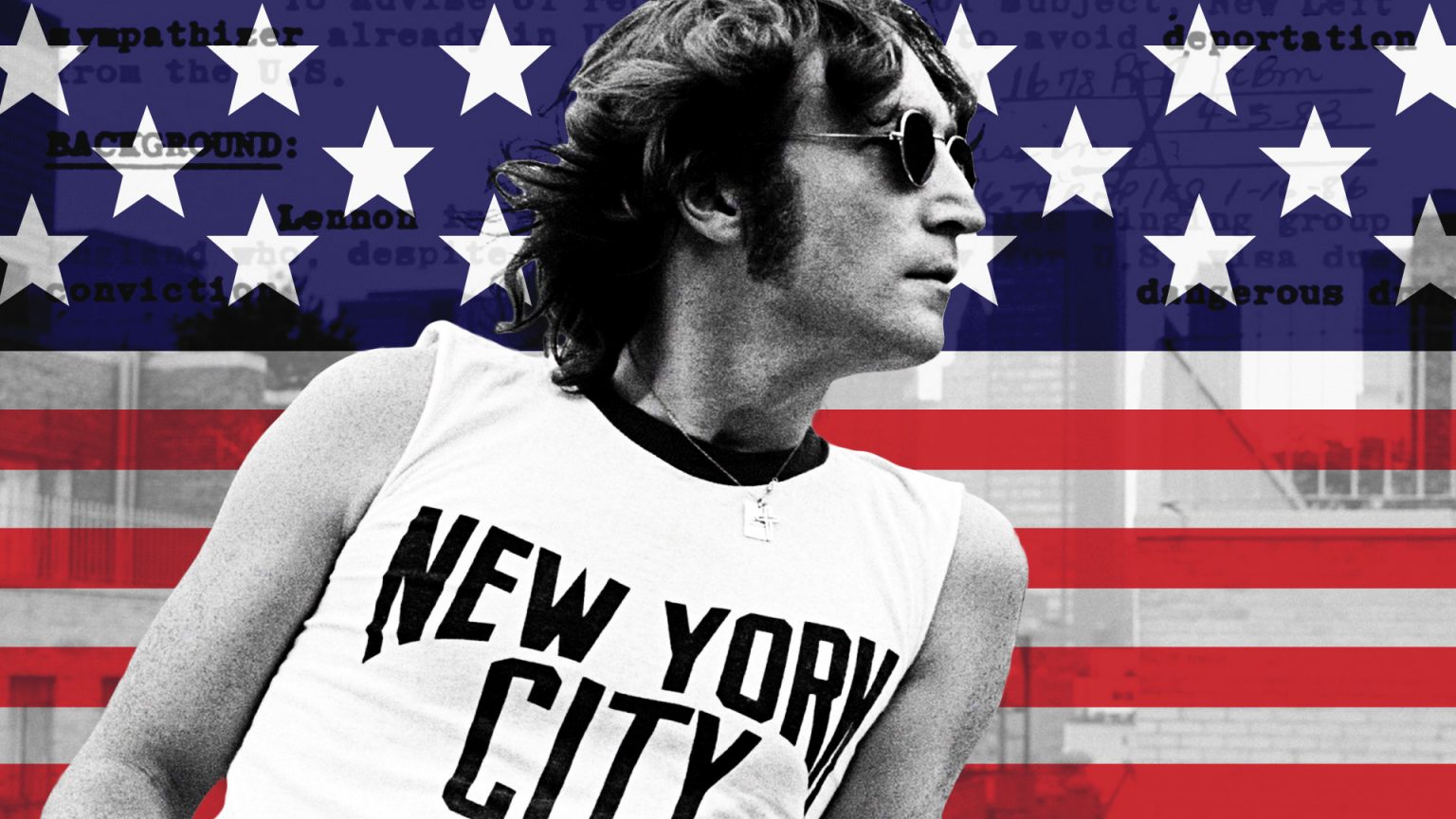

This movie’s title is not at all hyperbolic: For a period of time, the United States government really did pit itself legally and ideologically against musician, activist, and former Beatle John Lennon. Through copious amounts of archival footage and audio, along with interviews and a superb, Lennon-infused soundtrack, The U.S. vs. John Lennon details how the government—with President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office and J. Edgar Hoover running the FBI—sought to deport him. Though that time period (the late 1960s and early 1970s) may now seem a distant memory, the graininess of those archival recordings belies its many social, political, and cultural parallels to present-day America.

Back then the state of the world must have seemed pretty dire, too. The Vietnam War carried on interminably, ending in a stalemate that only further accentuated the tragic magnitude of the lives it altered. Nixon’s office was riddled with corruption, the National Guard at Kent State University killed four student protesters and, of course, in 1972, the government tried to deport one of the Beatles.

The case against Lennon, in essence, maintained that he was disloyal to the United States of America. Many of the film’s interviewees argue that, really, Lennon’s idealism and activism frightened Nixon and Hoover to such a degree that they believed him to be a threat to national security. White House communication records show that their initiative really was a political strategy aimed at neutralizing Lennon’s voice.

At the time, the artist’s political activism and outspoken idealism were widely publicized. In 1971, Lennon attended the John Sinclair Freedom Rally, a protest and concert held in response to the imprisonment of activist John Sinclair for possession of marijuana. Partly due to Lennon’s signal-boosting, Sinclair was eventually released, and the power of one person was on full display. Lennon was a glowing illustration that an individual really could change the world. But, as inspiring as that is, history repeats itself.

As the world of 2018 finds itself plagued by similarly upsetting issues, one can’t help but wonder about the lasting impact and the very efficacy of that “Lennon ideal.” In the midst of their immigration case, Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, introduced the idea of “Nutopia,” a conceptual utopia that they conceived of as a symbolic response to their situation. There was also the “bag event,” in which John and Yoko took interviews while sitting underneath a large white bag. Lennon maintained that doing so was an act of “total communication.” Covering themselves was a way of minimizing the significance of external appearance and individual identity so that their true voices could be heard unconditionally. The pair also held “Bed-ins For Peace,” where they stayed in bed in their hotel room and invited members of the press to speak with them about their political views.

Would people today take bed-ins and “Nutopia” seriously? The film frames those efforts as earnest and insightful displays of idealism, but John and Yoko lived in a different historical context. Lennon had just left the Beatles and had access to a massive platform. There was no Internet or social media; today, that sort of voice might be diluted by an endless stream of new content. Old footage shows crowds of people huddled together, collectively sobbing and mourning Lennon’s death. Nowadays, it is difficult to identify a lone artist, in any medium, who has the singular and seemingly universal pull that Lennon had. Even Lennon himself is viewed differently in 2018. Though still an icon, countless biographies now expound on his personal life, painting a more grounded and realistic portrait of him as a man with flaws like anyone else. That space of realism cracks the door for cynicism’s potential creep.

At times, The U.S. vs. John Lennon implores the viewer to interpret its lessons in grandiose terms; the title itself implies a David and Goliath narrative. Lennon eventually won his case and remained in the country, and one person really did beat an entire government. But Lennon was a massive figure, and he operated within a different cultural and political framework. That era was conducive to Lennon’s brand of idealism and provided fertile ground for an individual with his resources to have the kind of impact that he had.

In one interview, a reporter questions the nature of Lennon’s activism, and Lennon responds that he’s just doing what he, as an individual, is capable of doing. He says that’s all anyone can and should do: Just be yourself and do what you can with the tools that you have. (fragster.com) There is a paradoxical sense of humility underlying his grand actions— Lennon just happened to be the biggest musician in the world at the time, and his sweeping gestures and the widespread controversy they generated just happened to be how his activism manifested.

The U.S. vs. John Lennon is most striking in its editing—how well it interweaves archival footage to convey what the world looked like back then. In doing so, the film highlights the importance of studying the past. Watching the film, watching any film, is an exercise in re-experiencing history. That’s part of the medium’s power. Because the story itself is locked and never changes through repeat viewings, it serves as a litmus test for every new context in which it is viewed. That footage looked different to people fifty years ago. It looked different when the film was released in 2006, and it will look different fifty years from now. The issue, therefore, is not one of holding up Lennon’s activism to today’s milieu and wondering whether or not that sort of impact is possible. In fact, it may not be. Instead of encouraging us to ask not whether or not a revolution will happen, it encourages us to ask what it should look like when it happens.

WATCH NOW: The U.S. vs. John Lennon is streaming through the end of July on Fandor! It’s one of two films in our double feature, Lost Weekend, so don’t forget to check out its companion, Who is Harry Nilsson (and Why is Everybody Talkin’ About Him)? And, if Lennon has you thinking about how to change the world, be sure to dive into our spotlight on activism and resistance.