When The Truman Show was released in 1998, the concept of what privacy would mean in the information age was still relatively abstract. Cell phones were only beginning to become more common and few had cameras. The idea of a “surveillance state” lurked in dystopian novels like 1984 but if that culture felt like a real possibility, it seemed a distant one. Even the heyday of reality television was a couple of years away. The idea of a “post-privacy” world, in which your whole life could unwillingly be on display, was plausible but still alien. So as we look back on The Truman Show on its twentieth anniversary, it’s interesting to ask how has our understanding of the film changed?

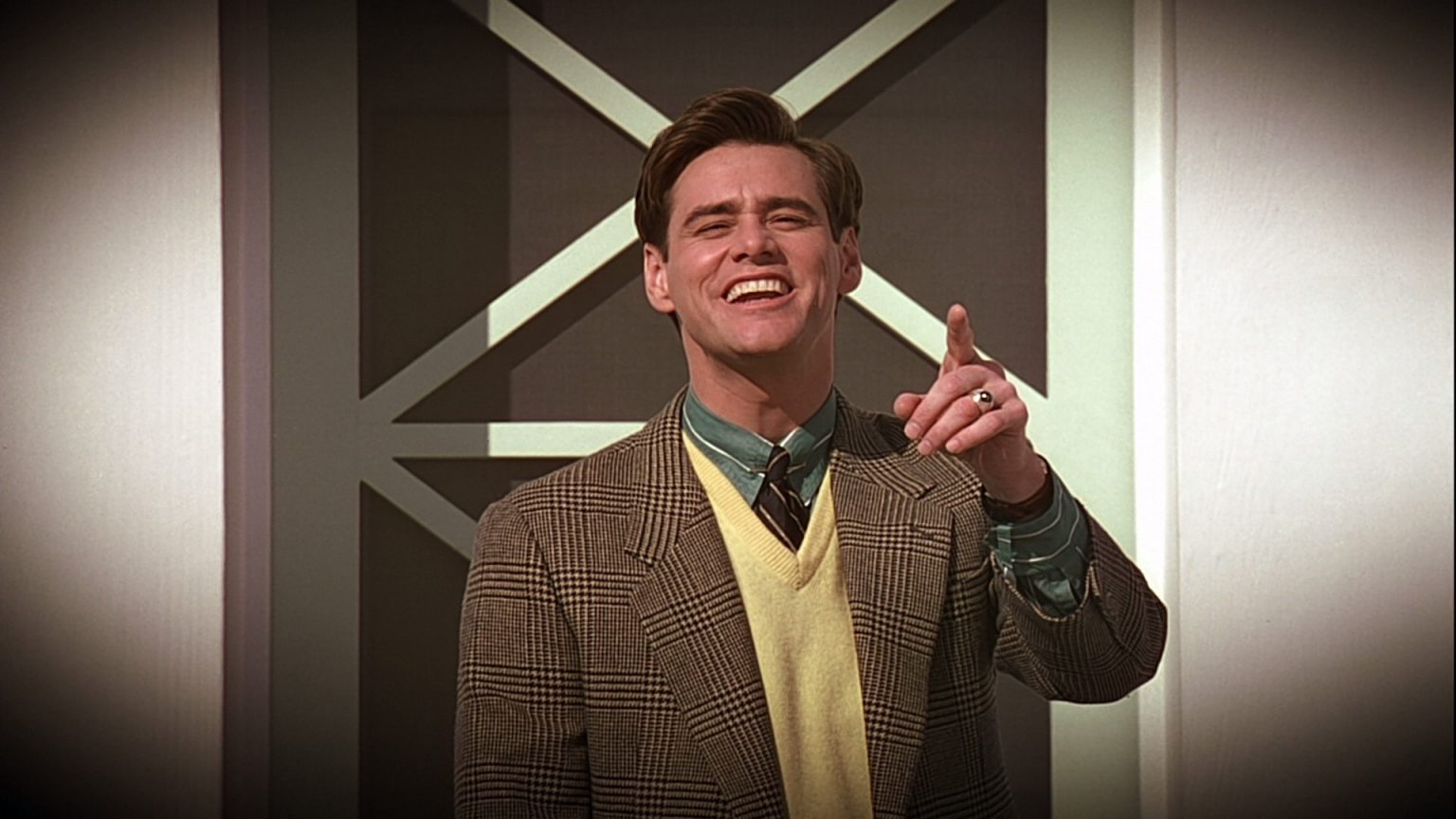

If you haven’t seen it, The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir and written by Andrew Niccol (who also wrote Gattaca), is about the titular Truman (Jim Carrey), who is unaware that his drab life as an insurance salesman is actually the subject of the world’s most popular reality show—a social experiment that began shortly after his birth. Over the course of the film, the cracks in his artificial reality begin to show until he is forced to make the choice whether to embrace the unknown or to stick with what he knows.

It goes without saying that a lot has changed since 1998. Not only has technology transformed but our relationship to it as well. Perhaps the most unexpected change is our own culpability and desire to forego our privacy in favor of presenting happy, curated lives for our social feeds. In the past twenty years, we turned the anonymous internet into something hyper-personalized. Unlike most past evocations of future states, the technological reality we live in is often bright, sunny, and too good to be true.

The Truman Show’s sunny cadence, which seems to mimic the nostalgia for the wholesome ideal of the 1950s, rings more true than most contemporary films that attempt to predict the future. Likewise, back in our own reality, people have embraced corporatization and have adopted the idea that we are all brands, ready to be packaged and sold. As we present our “best selves” on Instagram and Facebook, we are not inundated in the squalid browns and faded greys we imagine from the dystopias of our youth, instead, everything is bright and happy and charmed.

Study after study has confirmed that our relationship with social media is making us unhappy. And the artificiality of that world we admire or even aspire to, shares many similarities to the relationship viewers in the movie have with Truman. While Truman is not responsible for the curation of his near-perfect Brady Bunch existence, but instead an all-seeing God-like producer (Ed Harris), that relationship between viewer and subject operates on the same principle. Viewers, rather than use their time to focus on self-improvement, hobbies, relationships, or other things that could bring personal fulfillment or joy, instead focus their attention on watching Truman. They find comfort in the reliability of his existence but also measure their own worth against the accomplishments of his improbably ordered life.

What becomes increasingly apparent though, is that beneath Truman’s veneer of perfection there hide dark truths. Even casting aside the idea that he is living a lie, the Truman who goes out into the streets with a smile on his face contrasts to the more troubled Truman who struggles to find satisfaction in life. Truman’s life lacks intimacy as, unbeknownst to him, his private moments are dictated by corporate interests and social morality. His existence exemplifies the idea of the surveillance state, in which it doesn’t really matter if you are always being watched or not, you feel as though you might be. As a result, even in your private moments, you behave as though you are being watched.

Over the course of the film, Truman becomes increasingly anxious as he realizes something is amiss. Now, watching the strange corporate ad breaks as actors on the Truman show randomly shill for cereal is not entirely unlike targeted ad content that lifts from your conversations rather than your search history. Examples such as writer/designer Jen Lewis receiving an ad for an outfit she was already wearing last fall is likely a coincidence but nonetheless contribute to a sense of unease that moments we once thought were private might not be.

At the end of The Truman Show, Truman decides to step out of his perfect world into the unknown. The question is, would we do the same? Increasingly, the darker side of social media is rearing its ugly head, suggesting that it does far more harm than good. Beyond how social media affects us emotionally, there are scandals like Cambridge Analytica compiling our data in order to sway elections and real-world violence springing from fake Facebook news in places like Sri Lanka. These scandals echo one of the moral dilemmas at the heart of The Truman Show: are we in control of our destiny or are we acting according to a higher power?