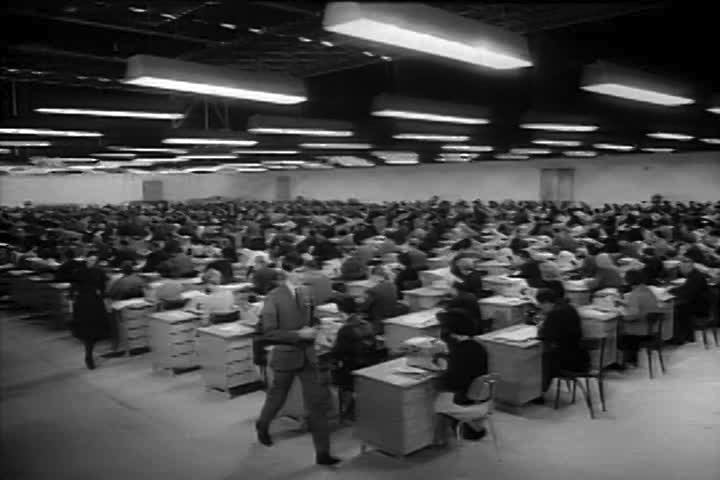

There is a shot in Orson Welles’s The Trial which, in the sheer scope of its conception, seems a veritable caricature of its director’s ambition as a visual stylist and craftsman. Josef K (Anthony Perkins, never more ineffectual), awaiting judgement following a decidedly ludicrous trial, returns to work in what appears to be an enormous warehouse converted into an open one-room office. The space is cavernous, but it is densely packed with workers hunched over typewriters on single-person desks. As Josef walks toward the camera from the entrance to his desk at the opposite end of the room, the camera tracks ever-backward, revealing as it does more workers and more desks in a seemingly endless white-collar expanse.

At the end of the line, Josef takes his seat before the camera, his many hundreds of coworkers held crystalline in deep focus behind him, their thousands of typing fingers generating a din that sounds distinctly like applause. Josef’s uncle Max (Max Heffler) arrives to express his concern and offer legal advice, but Josef, keen to avoid further trouble, insists that they not talk at length during working hours. But the very moment Josef finishes his sentence, it is as if he has dismissed the office with an inaudible cue: everyone in the room stops typing and stands in perfect unison, streaming from the room in single file with a speed and precision impossible to imagine of a crowd of this size.

In terms of the technical prowess on display—from managing the abundance of extras to the meticulous choreography required to depict their synchronized exit, as well as the more basic problem of how to keep so much space and so many people in focus while ensuring that the composition of the image remains dynamic and interesting—this single shot is as impressive a feat as the more widely lauded long take that opens Welles’s previous film, Touch of Evil, and which at the time had represented the pinnacle of his formal accomplishments. This sequence, like many throughout Welles’s career, gives the impression of conspicuous one-upmanship, as if the successful execution of a stunt so daring justified the attempt; but, as always with Welles, the fortitude with which he approached all things cinematic was not simply a matter of showing off.

With Welles, the camera is always expressive of an authorial perspective quite distinct from the subjectivity of the protagonist, even when the viewpoints are emotionally and psychologically aligned—think, for instance, of the distancing effect of the wizardry of Citizen Kane, whose sweeping to-the-rafters camerawork literally elevated us above the interiority of the drama. Welles, in other words, makes himself present in his films both onscreen and off, the brush strokes of his camera creating an indelible impression of the artist in the process of creating his work. And so when his camera appears to achieve the impossible—gliding through ballrooms in The Magnificent Ambersons, refracting in funhouse mirrors in The Lady From Shanghai, blowing up spaces in Othello—it is Welles the director as magician who is there pulling off the trick.

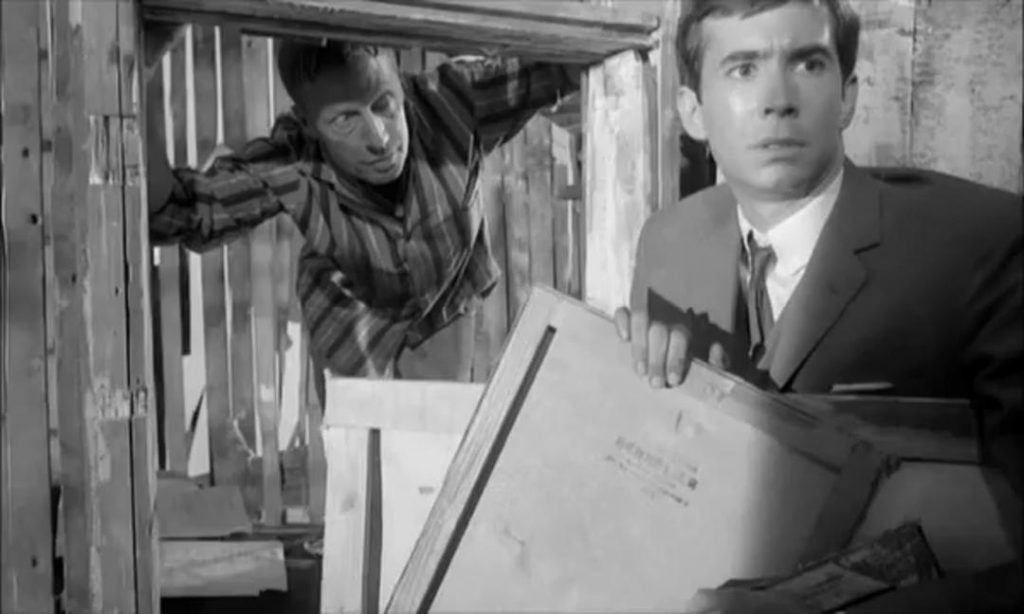

The Trial, of course, already has an author whose personal imprint is inseparable from the story it tells: every line is so thoroughly the work of Franz Kafka that any adaptation must defer to his style. And yet Welles was no stranger to the challenge of articulating classical texts anew: as with his three takes on Shakespeare, Othello, Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight, there is as much or more Welles in his version of The Trial as there is of its original author, and in the end the text has been so personally inflected that it seems to in some sense qualify as an original work. Welles’s The Trial is superficially faithful to both the narrative of the source text—Josef K has still been accused of a crime which is never explained to him—and to the feelings of paranoia and fear that pervade Kafka’s nightmarish vision. But the emotional tenor of the film, which in its sustained anxiety is truly singular, is defined more by Welles’s aesthetic predilections than by words lifted from the page, and it is for this reason that Welles’s The Trial is very much recognizably its own.

The look and feel of this film—an utterly bizarre spectacle of non-traditional framing, focus, and perspectives, shot in a harsh chiaroscuro—depends upon Welles’s technical expertise as much as his desire to both build off of and undermine his history as a filmmaker. That major sequence in the office is typical of the self-mythology the film conspires to deconstruct: it is at once the quintessential Orson Welles shot and a kind autocritical counterpoint to the same, exaggerating the director’s affinity for the grandiose in a context that seems to demand the opposite. It is a caricature of the expected Welles “bigness” of image precisely because the feeling at the heart of The Trial is internal, rooted in the mind: this is a “small” film, in the sense that its fears are located in the paranoia of one man wrongly persecuted, and yet Welles shoots it as if it were an epic.

It is common practice for filmmakers to express feelings of self-doubt and personal crisis using a visual language of proximity and intimacy—one expects, then, that The Trial will be shot with a probing camera and dizzying “subjective” effects, like John Frankenheimer’s Seconds. Instead Welles leans on a toolkit more suitable for a large-scale story, using the kinds of lenses which bring out backgrounds and other people within them. Josef K thus becomes not the most important character but almost the least, constantly de-emphasized by the swirling movement of hundreds of bodies around him (an earlier sequence, set in a massive courtroom, frames him meekly at the bottom of the screen, surrounded by a gallery of onlookers in an upper mezzanine). This is the real genius of The Trial: it is a movie about mental space—an unreal world that has, in Welles’s own words at the beginning of the film, the logic of a nightmare—that looks like a movie about a huge, indomitable world, one a man could get lost in. Welles jars us by making the nightmare all the more unfamiliar. It’s a trick Kafka would be proud of.