When Maya Deren first picked up a movie camera, she said it was “like coming home.”

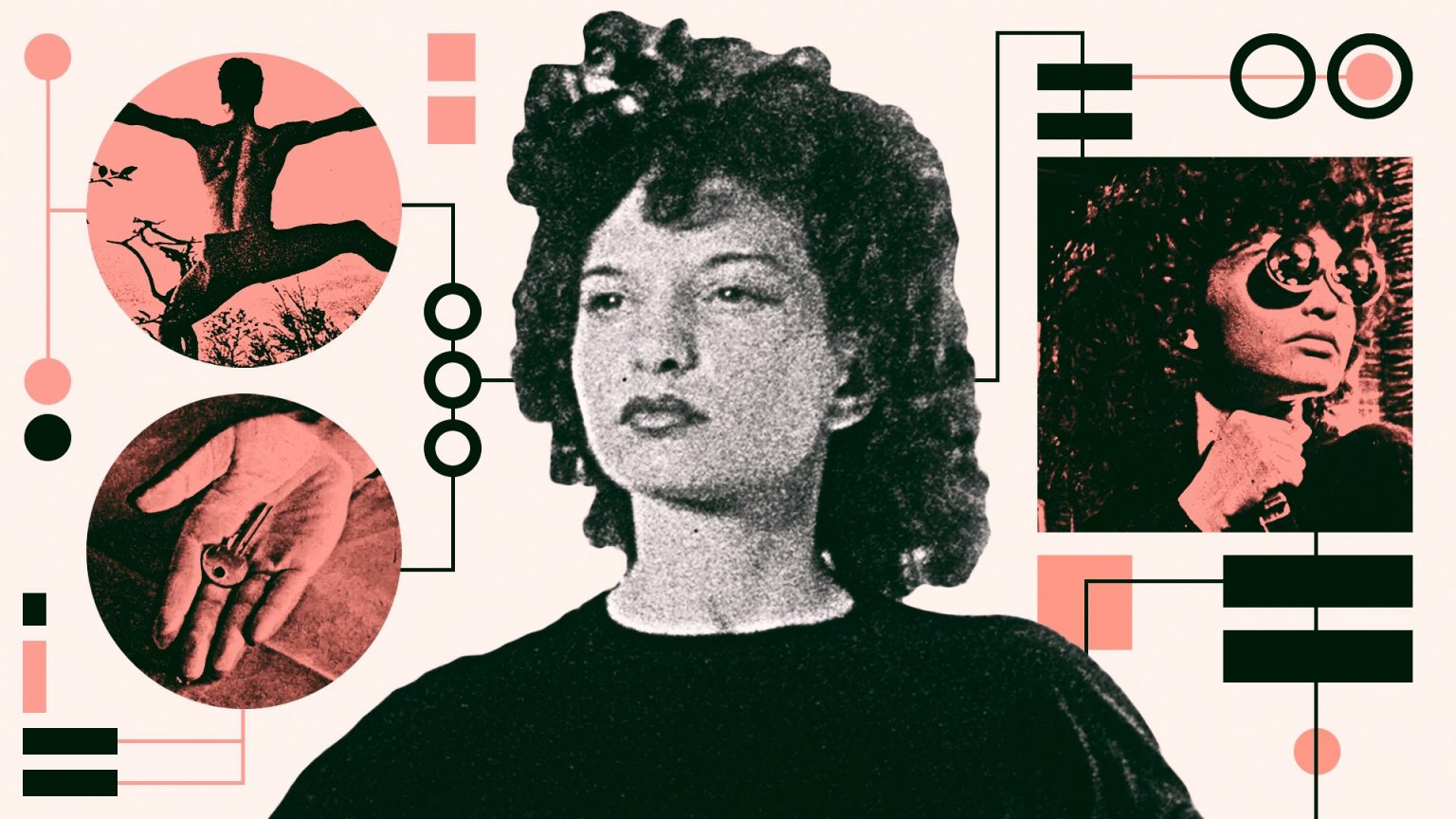

In 1943, equipped with a 16mm Bolex and a couple hundred dollars, working alongside Alexander Hammid, a Czech-born filmmaker and her eventual second husband, Deren directed her experimental breakthrough, Meshes of the Afternoon. A beguiling on-screen presence, Deren also starred in this fourteen-minute short, in which she drifts through a transient dream territory. From initial tonal tranquility — originally silent, Deren’s third husband, Teiji Itō, composed a score for the film in 1952 — Meshes of the Afternoon presents an uncanny salvo of evocative imagery, linked inscrutably together. The film is replete with shadows, barriers, and reflective surfaces: creeping silhouettes, an impeding windowpane, a cloaked figure with a mirrored face.

Deren spoke of an “aura” about her work, but she rebuked ties to cinematic surrealism, contending such productions favored provocative entertainment over profound significance. Nevertheless, her films still deliver a plethora of elements for those in favor of analytic interpretation: keys, knives, shattered glass, chess boards. Deren said of her mesmerizing debut (which was shot in twelve days), “It reproduces the way in which the subconscious of an individual will develop, interpret, and elaborate an apparently simple and casual incident into a critical emotional experience.”

Born April 29, 1917, in Kiev, Eleanora Derenkowskaia’s last name was shortened to Deren by her psychiatrist father — later, Hammid would dub her Maya, a moniker meaning water and one evoking the Hindu goddess of illusion. It was a fitting name for such a mutable artist, who seamlessly transitioned from poetry, to dance, to film, while also combining those forms and more. Changing one’s name is to change one’s identity, and Deren was appropriately fond of doppelgangers, bodies broken into abstract partitions, and changing one’s behavior for ever-spontaneous situations.

Essentially picking up where Meshes of the Afternoon leaves off, Deren’s At Land (1946) begins with her beached figure washed over by crashing waves, instilling a sense of perpetual metamorphosis. And like Meshes of the Afternoon, the fragmentary focus of At Land is not only physical — isolated glimpses of fingers and hands, eyes and lips and feet, bodies twisting and climbing and stretching — but environmental. Deren crawls from the shore to a banquet table, to an abundant forest — and efficiently edited, incongruous, boundless advance. It is an exploration Deren likened to “a birth or passage from one element into another.” It is also measured progress, feminine progress according to Deren. At Land, she says, is “the film of a woman,” with the “time quality of a woman.” “A woman has the strength to wait,” Deren affirms, “because she has had to wait.”

A year later, on Long Island, A Study in Choreography for Camera (1946) fixed on dancer Talley Beatty as he pirouettes from space-to-space, exterior to interior, always in balanced harmony with Deren’s methodical vision. “In the film,” she proclaimed, “I can make the world dance.” And indeed, she does, rotating and panning, restlessly, gracefully, often independent of Beatty’s physical bearing. In her 1948 film, Meditation on Violence, the body and camera are similarly linked. Violence exhibits a purity in its singular focus and lack of illusory effect; this twelve-minute exercise follows Chinese boxer, Chao-Li Chi as if he were an intuitive extension of the camera. According to Stan Brakhage, Meditation on Violence was Deren’s most personal film: “She is the camera,” he said, “she’s moving, she’s breathing in relation to this dancer.” The result is a sinuous beautification of an ostensibly violent performance.

Between A Study in Choreography for Camera and Meditation on Violence, Deren collaborated with Anaïs Nin and dancers Rita Christiani and Frank Westbrook for Ritual in Transfigured Time. Where a film like Meshes of the Afternoon feels more hesitant, in this 1946 release, dance provides a liberating relief from social and domestic inhibition. This perception of liberation is expanded in The Very Eye of Night (1958). Featuring the talents of the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School and choreographer Antony Tudor, this so-called “astral ballet” is an ethereal fifteen-minute reverie, with celestial cutouts and superimposed bodies in a floating migratory constellation.

The same year Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon won the Cannes Film Festival’s Grand Prix Internationale for 16mm experimental film, she was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship to research Haitian culture and the rituals associated with Voudoun (voodoo); she had an affinity for the mysterious practice, with its transcendent emphasis on dance, music, and ceremony. Amassing some 18,000 feet of footage, Deren’s intended film instead became the piecemeal documentary Divine Horsemen, which was finally compiled after her death (at the age of forty-four, of a cerebral hemorrhage).

Well-educated, well-traveled, and politically savvy, with an avid circle of friends and collaborators (roles frequently overlapping in the avant-garde world), Deren also wrote on the nature of cinema, eloquently debating its potential. Employing slow motion to scrutinize the intricate nuances of a kinetic physique, magnifying time, pushing postmodern boundaries of continuity and structure, Deren realized an endlessly mobile form could become, in effect, unbridled and formless.

Quick to acknowledge the financial, creative, and technical difficulties of filmmaking, and the passion necessary to persevere in the face of these hurdles, Maya Deren put forth an inspired, pioneering body of work. Though minimal in quantity, it remains a phenomenal collective accomplishment.

Watch Now: The Films of Maya Deren including the films mentioned here, Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, Meditation on Violence, and Divine Horsemen.