There are times after watching commercial theatrical releases when I struggle to muster enough enthusiasm to write even one appropriate sentence in response, obliged as I might be to some earnest publicist expecting a compensatory pound of flesh for a comped ticket or a festival badge. Such films more often than not fade swiftly from my memory like morning mist in direct sunlight. In recent years, rather than have my body decimated by obligation, I’ve elected to support the industry of filmmaking by preserving my silence and buying a ticket like every other moviegoer. Nor am I motivated or entertained by ranting over how conspicuously mediocre most contemporary movies have become, like many front line reviewers who could readily be roaring extras in a Roman coliseum, gesticulating thumbs down, while innocents are being fed limb by limb to the lions. I quietly leave the theater and go home and splash cold water on my face. “They’re only movies,” I tell myself, staring vacantly at my reflection as the roar of the coliseum subsides.

But now and again I watch a movie that doesn’t allow itself to be “just” a movie. And maybe it’s a film that’s nearly fifty years old, alluringly freed from market pressures, but still so incredibly current and relevant that it won’t let go, demanding articulation and praise, insisting on being understood through language, and thereby undeniably elevating itself into the so-called seventh art by the sheer force of creative, competent will. Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s The Gospel According to Saint Matthew (Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo, 1964) is one such film. I sometimes wonder if I am ever going to stop writing about this movie? Though, truthfully, I am delighted I even want to.

During these last few weeks I have been asking myself just why Pasolini’s Matthew has taken such a hold on me? The painterly quality of the film does seem to hold me in contemplative orbit even as its narrative urgency speaks to the gravitational pull of political necessity. It abounds with conflicting energies: acknowledged as possibly the best film about the life of Christ, made by an affirmed Marxist atheist homosexual. Peter Bradshaw’s description for The Guardian that Matthew “looks as if it has been hacked from some stark rockface” comports with Bosley Crowther’s earlier comment in his New York Times review that the film’s language is “flinty,” suggesting Matthew‘s essential beauty is lapidary. There’s a sculpted quality to Matthew, perhaps more rough-hewn than burnished, constructed as an homage to neorealism yet contaminated by stylized, purposeful anachronisms. Like the best pieces of Christian art, Matthew speaks to the history of Christian art, and situates itself along a vast continuum. In this historical layering it resembles something sedimentary.

I’m not a Christian. I’m not going to pretend to be. But I was raised in the Catholic faith and I cannot escape an imbedded sense of the cultural importance of the Bible as spiritual literature, specifically the narrative of The Passion. I know that having to believe is as important—if not existentially more so—than believing. I believe faith and knowledge do not cancel themselves out but are symbiotic by design. I have to believe that.

When I was researching Pasolini, I was struck by his devout atheism, his refusal to believe that Jesus Christ was the Son of God, but also his awareness that the teachings of Christ—more today than ever—may speak to revolutionary purpose. Pasolini may not have been a religious man; he may not have even been a spiritual man, but his sensibility was certainly mythopoeic, with a deep respect for the sacred, which he believed revealed itself through nature. He felt the sacred surfaced both in landscape and the human body. I have no difficulty understanding that and appreciate how interwoven this is in his cinematic vision. It’s not so much that the Gospel According to Matthew confirms a Christian viewpoint as it does a revolutionary and sacred one.

In his review of the film, Roger Ebert understands that there is no single version of the story of the Passion. “It acts,” he writes, “as a template into which we fit our ideas, and we see it as our lives have prepared us for it.” For me, that’s exact phrasing. As someone raised in the Catholic faith, I nonetheless always felt outside of it, partly because of the Church’s stance on my sexual orientation. This caused me to engage in a debate with organized religion for many years and I educated myself on the early history of Christianity and its mythic antecedents in Assyrian-Babylonian narratives, as taught to me by comparative mythologists Joseph Campbell and Nanos Valaoritis. As a full scholar for San Francisco’s C.G. Jung Institute over 20 years, I studied with Bible historians such as Elaine Pagels and Karen Armstrong and Gnostic scholars such as Gilles Quispel who, in fact, helped smuggle The Gospel of Thomas out of Egypt at Jung’s bequest. Thomas, in fact, became my favorite of the gospels, even if excluded from the official canon. I studied with Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, who both advocated an appreciative perspective of the Historical Jesus. One could argue this is the same perspective applied by Pasolini in constructing The Gospel According to Matthew.

During my theater years I was given the chance to play the apostle Peter in Magdalen, a production that incorporated the Gospel of Thomas verbatim within the script, and I can recall to this day how powerful it was to enact words written millennia ago. It felt as relevant as it felt ritualistic. Thus, I have a clear appreciation of Pasolini’s similar experiment of incorporating the Gospel of Matthew verbatim into his filmic adaptation. These experiences—studying the history of Christianity, the Gnostic Gospels, and the Historical Jesus, along with enacting the Gospel of Thomas on stage—is what prepared me (in Ebert’s sense) for viewing Pasolini’s Gospel According to Saint Matthew. What follows are my responses to Pasolini’s project, negotiated through a second, more informed viewing after researching the film.

The Iconic Countenance

The face as icon reveals the sacred through countenance, where countenance is understood as an interaction between mind and heart. Pasolini’s film starts out with close observances of the faces of a young woman and a slightly older man. Without either being identified, without a word being said, Pasolini defamiliarizes the standard Passion narrative by keeping the audience guessing as to their identities. Why is this young woman so troubled and tentative? Why is this man at turns near-angry and seemingly frustrated? As the camera pulls back, you see that she is pregnant and it’s only then that you deduce she is Mary and he is Joseph. Clearly this is not Joseph’s child and he’s not sure how to handle the situation. He walks away from her to clear his thoughts, tires, stops to rest and dreams. In his dream he is visited by an angel who tells him to rejoice that Mary has been impregnated by the Holy Spirit. Until the angel speaks, nothing has been said aloud, the narrative has followed Matthew’s description in his gospel, and the story has been told purely, through images, through iconic countenances, staged in frontal compositions against backgrounds that suggest Byzantine art. Even after Joseph has received the good news, the ensuing scene returns the film to silence, relying on a relay of facial expressions to express Joseph’s willingness to father the holy child, and Mary’s relief in his willingness to do so. They both smile demurely, tentatively, as they accept parentage as their sacred fate.

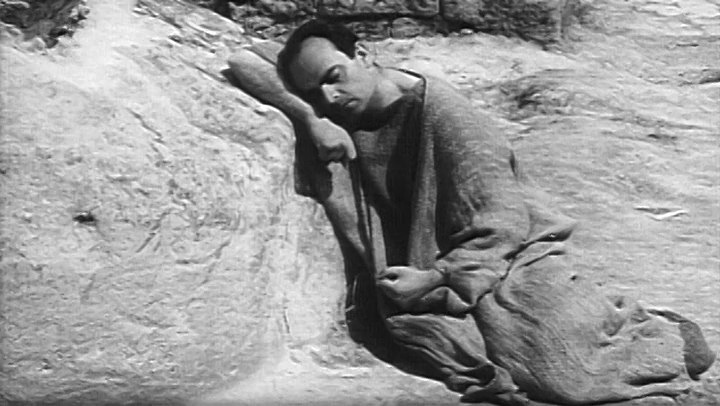

This visual device continues well into the film, both to introduce familiar characters to the narrative, but also to profile the social world within which the narrative rests. It did not go unnoticed by detractors at the time that many of the faces used by Pasolini were those of the disenfranchised people he knew from the borgata, the slums of Rome. Straight off, through visual countenance alone, Pasolini has rendered a class critique, casting his Passion narrative with members of a discriminated class, non-actors who by their very being, their countenance, reflected authenticity and—through the “authentic”—the sacred.

Kenneth Turan considers Pasolini’s “marvelous faces of local people, each one a book in itself.” Russell Hittinger and Elizabeth Lev find their iconicity somewhat strange and grotesque, serving to disarm spectatorial imaginations that have been liturgically and textually informed. At Little White Lies, David Jenkins writes: “One thing that connects all of Pasolini’s films is the unflinching way he photographs faces and bodies, finding a tremendous, grotesque beauty in the extras and supporting cast, displaying an almost Christ-like empathy towards all of God’s creations.“

At the London Review of Books, Michael Wood likewise extols the achievement of Matthew‘s opening sequence, and Pasolini’s repeated usage of the iconic countenance to further the Passion narrative. “Again and again,” Wood writes, “we see faces—of Peter, of Judas, of Jesus himself—before we see anything else. They stare out of the frame at us, often expressionless. We stare at them and wait to know what they are looking at (apart from us, that is), what they can see inside the frame of their own world. We can often guess what it is, since we know the story, but it’s tempting to wait anyway, just to let the weird non-acting work on us. This is not a matter of the neorealist trick of using amateurs, as if amateurs were somehow more real than professionals. ‘You are working, aren’t you?’ Brecht used to say to his actors. It’s a matter, as I have already suggested, of not acting at all, whether you are any good at it or not. It’s a matter of being photographed. The faces talk, not the expressions on them, or the absence of expression. In their differences from each other, in their actuality, their sense of belonging to a particular place and time (Italy, 1964, not Palestine, 28), they enact not the story of Christ but the mystery of the story.”

In a slightly variant—though no less interesting take—Ara H. Merjian (author of the upcoming Heretical Aesthetics: Pier Paolo Pasolini Against the Avant-Garde, to be published in 2014) traces the affinities and contradictions between the unlikely pair of Pasolini and Andy Warhol in his advance think piece for Frieze magazine entitled “Mascots & Muses“, which—in effect—eroticizes (i.e., queers) Pasolini’s visual strategies. Merjian writes: “Notwithstanding the ideological chasm that separated them, Pasolini’s and Warhol’s eccentric orbits overlapped in a number of instances. Apropos of eccentricity, critics accused both men’s work of unreconstructed narcissism—a thinly veiled euphemism for homosexuality and its bearing upon their art. Each, however, held at bay his identity (or identification) as a gay man, even as he helped to shape queer culture before Stonewall. Both enjoyed the company of mascots and muses, drawing upon them for artistic collaboration and personal frisson alike. The slow succession of apostles’ faces in Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) recalls nothing if not Warhol’s contemporaneous screen tests, a mix of eroticism and transcendence in their own right. Both Warhol and Pasolini availed themselves of delinquency (not to say criminality) as the stuff of aesthetic experiment.”

As an aesthetic (if eroticized) experiment, the casting of the Apostles is equally noteworthy for reflecting Pasolini’s literary acquaintances and suggesting Pasolini’s sly projection of himself onto the figure of Christ (despite choosing someone else to portray Jesus). Otello Sestili, who played Judas Iscariot, may have been a ruggedly handsome truck-driver from Rome; but, Enzo Siciliano (Simon), became Pasolini’s first biographer years later with his 1995 volume Who Killed Pasolini?; Alfonso Gatto (Andrew) was an author, poet, art critic and painter who later played a physician in Pasolini’s Teorema; and Giorgio Agamben (Philip) was an eminent intellectual and philosopher. Of the other twelve, most were—as Merjian described them—”mascots” that Pasolini had discovered in the slums, and only the quite beautiful Luigi Barbini (James) joined Pasolini’s ensemble after sidetracking momentarily into the sword and sandal feature Hercules the Avenger (1965). Barbini returned to work with Pasolini in Porcile and Medea, but most notably in Teorema where he wordlessly seduced Massimo Girotti in the train station with a proffered crotch.

The Massacre of the Innocents & The Visitation of the Wise Men

Several narrative challenges were presented to Pasolini in adapting Matthew’s gospel to the screen; a gospel known less for narrative continuity and cohesion than for episodic moments depicting Christ’s life and ministry. As Raymond Durgnat indicated in his critique for Films & Filming, Pasolini always responded intelligently to the challenges built into each episode, “but with varying success.” Durgnat was critical of Pasolini’s robust enactment of Herod’s massacre of the innocents—which he considered “historically dubious”—and felt there were more important narrative elements Pasolini could have pursued but didn’t. As is, however, Kenneth Turan thought Pasolini’s usage of the music Prokofiev wrote for the German slaughter of babies in Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky fit perfectly for the scene, though Covey—having difficulty suspending disbelief—countered with a less appreciative take: “Herod’s slaughter of the innocents provides some scenes that are both shocking and—at least, as I have always found them—unintentionally hilarious. The mothers running from the slaughtering soldiers with babes in arms are clearly carrying dolls in many cases, and when some of them are thrown in the air this becomes far too obvious, in a classic Saturday Night Live dummy-throwing sort of way.”

Jesus as Non-Actor

Pasolini condenses the biography of Jesus into three swift temporal strokes. Jesus is born and visited by the wise men, he is next shown as an infant of three or four, and then as a young man of thirty-three. As an infant, he obeys Joseph’s call and comes running towards him with a toy sword in his hand. Straightaway through such a tender image, Pasolini signals the revolutionary Jesus. By the time Enrique Irazoqui appears on the screen, we are ready for a spirited Jesus zealous for rebellion, if not a unibrowed Jesus whose role could easily have been snagged by Zachary Quinto were the film being made today.

In her March, 2004 piece “The Jesus Christ superstars; From DeMille to The Passion of The Christ, movies of the Gospels story have been charged with controversy” written for The Herald (and available through Highbeam Research), Hannah McGill outlined Irazoqui’s involvement in the project. McGill writes: “Arguably the most striking screen Jesus wasn’t even an actor by trade. Enrique Irazoqui was a Catalan economics student and political activist, who, at the age of nineteen, visited Pier Paolo Pasolini to discuss the film-maker’s work and to seek his support for the Spanish leftish movement. Pasolini, who had been searching for a lead for The Gospel According to Saint Matthew (1964), was struck by Irazoqui’s resemblance to the long-faced, wide-eyed, sorrowful Christs of El Greco’s paintings. ‘Even before we had started talking,’ the director later recalled, ‘I said, ‘Excuse me, but would you act in one of my films?’ Irazoqui’s own response, as he later remembered it? ‘I told him I had more important things to do, like the construction of the universal brotherhood.’ Irazoqui was eventually persuaded to see the points of connection between Pasolini’s mission and his own; but he provided only the physical presence required by the film. His lines were dubbed by the actor Enrico Maria Salerno [who Tony Rayns identifies as “the same man who voiced Clint Eastwood in his Leone westerns”].

“Some were far from convinced. Pauline Kael referred to Irazoqui as ‘a loathsome, prissy young man,’ whose crucifixion she positively welcomed. Certainly he’s a frail, smooth-skinned boy; it’s not easy to accept that he’s thirty-three years of age, or butch enough to have ever earned a living as a carpenter. But Irazoqui’s lack of narcissistic actorly affectations was suited to the film’s austere style, while his unsettling combination of hauteur and vulnerability fitted Pasolini’s volatile, unpredictable Jesus. Meek and mild one minute, stormy-browed and threatening the next, this is the difficult, contradictory Jesus who preaches forgiveness but also declares, “I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.’ He also appears insecure about his own effectiveness; Pasolini emphasizes his tendency to fret and complain when attendance is patchy at his sermons, and to promise chastisement for those who fail to follow him. Rather than emanating sleek self-containment, and issuing forth perfectly finished nuggets of wisdom, Pasolini’s Christ is stroppy and troubled, only sporadically confident about his own duties and responsibilities.

“Upon his return to Spain after shooting, Enrique Irazoqui had his passport confiscated by the Franco government for appearing in a film they considered to be Marxist propaganda. In later years, he became a noted economist and a professor of literature. Most intriguingly, he has earned an entirely separate fame, as a chess master and the creator and organizer of the world’s largest chess computer tournament. A lifelong agnostic, Irazoqui now says: ‘I have not returned to read the Gospel, and the relation that I have with Christ is through people who ask me.’ ” In another piece for The Scotsman, “A Story To Die For” (likewise on Highbeam), Hannah McGill, detailed that Enrique Irazoqui not only had his passport confiscated but was sentenced to fifteen months’ hard labor by the Spanish government.

At The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw described Enrique Irazoqui’s portrayal of Jesus as “eerily, almost disturbingly self-possessed, emerging from the landscape like Bergman’s Death in The Seventh Seal. His rhetoric is ceaseless and fluent, and his sermonizing is persistently presented as a kind of dreamlike montage of inspired insights and mysterious aperçus, with Pasolini’s camera jump-cutting from Jesus’s face at different places and times. This really is raw film-making, in a political vernacular which speaks of Pasolini’s high, theocratic Marxist belief in the sovereignty of the people, like the publicans and the harlots that Christ said understood him.”

Baptisms of Divine Silence

One of Pasolini’s strategies to work out the challenges of adapting scripture to screen was to create a parallel narrative between Jesus and John the Baptist (Mario Socrate), who Bosley Crowther described as “a subdued firebrand in a poet’s angular frame.” Philip French described Socrate as “scrawny, balding, undernourished, with a mouthful of bad teeth and the radiance of a true believer.” For me, however, the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist at the River Jordan links The Gospel According to Matthew to a later version of the Passion: Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988).

Countenances that express themselves through non-verbal communiques differ significantly if slightly from a related yet separate element in Pasolini’s narrative that impressed me when I first watched the film; that of divine presence as silence. As synopsized earlier, in the film’s opening sequence Joseph has wandered away to work out his thoughts and feelings. He wearies and stops to rest and—just before falling asleep—watches some children noisily playing. He is bolted awake by complete silence and—where the children had been playing—now stands a solitary figure, a beautiful and slightly androgynous angel (Rossana Di Rocco), who speaks the will of God.

Perhaps this would not have caught my attention had I not already observed the same cinematic strategy in The Last Temptation of Christ when John baptizes Jesus at the River Jordan. As that scene is introduced in Scorsese’s film, the River Jordan is flanked by penitents and zealots, several whipping themselves, emitting cries of pain. When John baptizes Jesus, suddenly there is complete and total silence. Scorsese’s camera pans the riverbank—the self-flagellators are still jumping up and down and whipping themselves—but there are no cries, no sound at all. This was Scorsese’s way of depicting the descent of the Holy Spirit who speaks the word of God, “This is my son in whom I am well pleased….” Scorsese, of course, doesn’t require these words to be said aloud because those who know the story are familiar with what the Holy Spirit says. It’s a potent ellipse: delivering a familiar line of dialogue in a well-known story through complete silence. At the time I saw The Last Temptation of Christ, I considered this downright brilliant; but, now that I’ve seen Matthew, I would be interested to determine whether Scorsese lifted his interpretation of divine presence as silence directly from Pasolini’s Matthew?

One final visual element that intrigued me within Pasolini’s rendering of the parallel narrative of John the Baptist is how he shows Salome, quite a young girl, playing jacks before being called to dance before Herod. Her childish innocence makes her request all the more brutal. How chilling that such a lovely traipsing dance could result in a severed head on a plate.

The Miracles

To depict the miracles written about by Matthew in his gospel, Pasolini had to create his film as if he believed in these miracles—or, more accurately, as he knew others believed in them—but, such divinity is problematic for a revolutionary, historic Jesus and might not have necessarily even been Pasolini’s point, which might account for why Pasolini presents the miracles so matter-of-factly—more as a discourse on how miracles have traditionally been depicted cinematically—and how cinematic tradition comports itself with a religious one, both to advance the narrative strategies of each other. Pasolini fulfills the tradition, but not without slyly winking and revealing this age-old collusion.

As astutely observed by David Jenkins at Little White Lies: “Even though Pasolini’s film offers traditional religious nourishment aplenty, there is still the sense that he’s delicately manipulating the material to mine a more sophisticated seam. The manner in which he films the actual miracles is fascinating: they all occur very suddenly with a single cut. Not only is he happy to accept that Jesus was able to perform physical miracles, he also makes a point about cinema. For Pasolini, every cut is a potential miracle.”

At The New York Times, Bosley Crowther writes: “The cryptic performances of the miracles—the healing of a hideously grotesque leper, the feeding of the multitudes, the walking on water and others—are pictorially done so that they seem the simple, straight, quick-change recordings of inexplicable phenomena.” At The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw describes he healing of the leper as bearing a “