How a filmmaker interprets a book for the screen is always interesting to examine. There is inherently less space on-screen than in a book, so the filmmaker, through necessity, is forced to choose what they deem important and what they feel can be cut and changed. In the case of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, this need for examination is furthered by there being two adaptations of the book, a Swedish version, directed by Niels Arden Oplev, and starring Noomi Rapace and the late Michael Nyqvist and an American version, directed by David Fincher, and starring Rooney Mara and Daniel Craig. Both movies are generally well regarded but feature vastly different interpretations of the source material. Here, we will examine how, while the American version is more stylistic and hews closer to the book, the Swedish interpretation is the superior version of the story.

Though the movies diverge in tone and character creation, they still, oddly, hit many of the same beats at approximately the same points in their respective runtimes. This is especially interesting because of how Fincher and Oplev choose to frame their versions of the story over the first thirty minutes. The difference in tone is exemplified at the outset by the opening credits. On the left, we see Oplev’s utilitarian credit sequence: Stark white letters superimposed over the two most important people in the story—Lisbeth Salander and Harriet Vanger, the subject of the film’s central mystery. The credits in Fincher’s version set a wholly different tone. The titles are stark and stylized and the credit sequence draws the audience out of the movie into a James Bondian psycho-sexual fever dream, while a strange (and not very good) version of Led Zep’s “Immigrant Song” plays in the background.

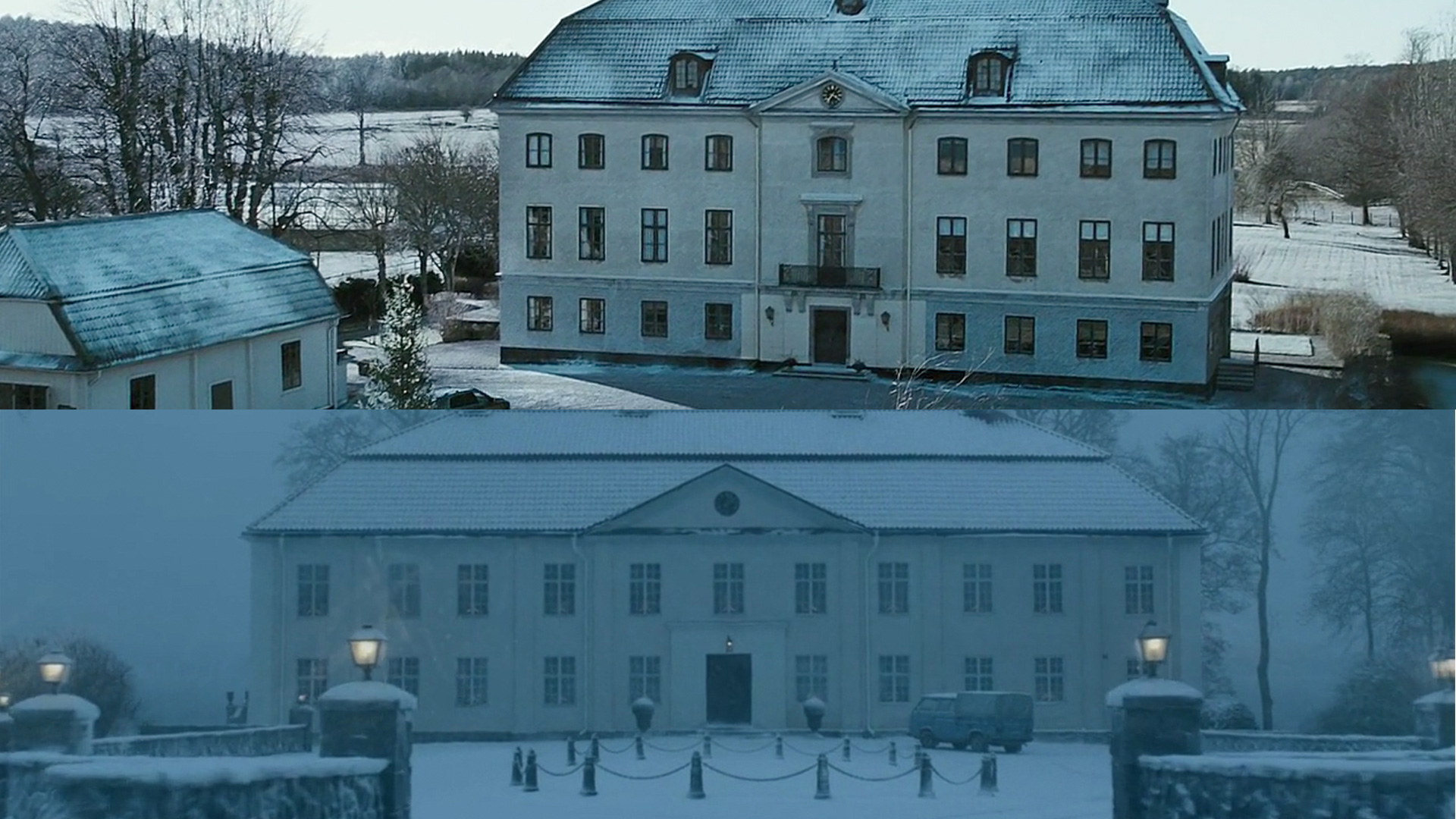

This same idea of “style vs. utility” is further exemplified by how the directors shoot their films. Fincher shoots many of his scenes like this one of Blomkvist approaching the Vanger mansion for the first time. Here, he frames the house in the center, bringing out the symmetry of the composition and imbuing the building with a dark, almost haunted air. While Fincher shoots the mansion from the perspective of the approaching car, Oplev chooses, again, a more utilitarian shot that captures both the mansion and the approach of the car. Here, the American version is benefitted from the more stylized cinematography, which turns the mansion and the secluded northern island into characters unto themselves.

How the filmmakers handle the transmitting of needed story information is also vastly different. In the above shot, Oplev’s characters watch a reel-to-reel while relaying the backstory of Harriet Vanger’s disappearance. Below, Fincher chooses to reenact the scene through flashback (though who’s the memory it belongs to is a little mysterious), while choosing a sepia grading for the sequence. These choices feel needless, sloppy, and just a little bit hacky compared to the practicality of revealing this information through found footage within the world of Oplev’s film.

Next, it’s interesting to examine how each director handles the backstories of their two main characters. Strangely, though Fincher spends more time on establishing his characters and their relationships with other people, he seems to get less out of these sequences than Oplev. Where Fincher depicts the relationships between Salander and her guardian (who’s stricken by a stroke) and Blomkvist’s romantic relationship with co-worker Erika Berger (Robin Wright), Oplev chooses to simply imply these relationships. To him, these are not the focus of the story, so it’s important to bring them up and move on quickly. Fincher’s Salander visits her guardian, finds him collapsed, and waits for the prognosis in the hospital; Oplev’s Salander receives a phone call informing her of her guardian’s stroke and that’s the end of it. Likewise, Fincher’s Blomkvist has a deep relationship with Berger that colors the entire story; Oplev solves the complexity of their relationship with a simple glance shared between the two characters.

How these characters are built and depicted diverge wildly from this point. By the time the two characters meet, they are vastly different between the two movies. Simply put, Oplev respects Salander more than Fincher. In the Swedish film, Salander works on Blomkvist’s case behind the scenes and only reveals herself when she’s ready to get herself involved. When Blomkvist tracks her down, he is already in awe of her skill and is appropriately reserved. Fincher’s Blomkvist tracks down Salander, literally busting in on her in a show of bravado that’s tantamount to an invasion. Though Blomkvist gives Salander the choice of whether to work together or not, she is denied the opportunity of refusing the meeting in the first place. This divergent scene of the two characters colors their relationship and how the audience perceives them—Oplev, for the better, and Fincher, for the worse.

This brings us to the climaxes of the films and where, ultimately, one version succeeds and the other fails. In both versions, after rescuing Blomkvist, Salander chases after sadist Martin Vanger on her motorcycle. In both versions, Vanger flees in his car, only to crash off the road. In Oplev’s version, Salander approaches the car and watches, almost ecstatically, as Vanger pleads for help before the car explodes in flame. In Fincher’s version, the car explodes before Salander has a chance to make the decision of whether to save him or not. Again, Fincher robs his character of her agency, and by doing so takes from her the moral ambiguity that makes Oplev’s version of the character, and the movie as a whole, so interesting.

Watch Now: The entire Swedish Millennium Trilogy—The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest.