The Girl: A Life in the Shadow of Roman Polanski by Samantha Geimer, states its case most succinctly when early on in the text one of its three authors, attorney Lawrence Silver, declares “No matter what his crime, Polanski was entitled to be treated fairly; he was not. The day Polanski fled was a sad day for American justice. Samantha should not be made to pay the price. She has been paying for a failed judicial and prosecutorial system.” That’s correct, though the price paid by Polanski and Geimer can’t truly be called equal or comparable, and the three authors don’t truly try to do so.

I say three authors for while The Girl is nominal written by Samantha Geimer, the teenager whose parents in 1977 reported to the police a sexual dalliance leading to the world-famous filmmaker being charged with “rape by use of drugs, perversion, sodomy, lewd and lascivious act upon a child under 14, and furnishing a controlled substance to a minor.” Said charges were knocked down following his guilty plea to “unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor,” a fact Polanski’s many critics rarely mention. But attorney Lawrence Silver, the book’s most important voice certainly does so. Documenting precisely what Polanski was charged with, convicted of and why, and detailing the irresponsible conduct of Judge Lawrence Rittenband, whose failure to bring the case to a proper conclusion led to the filmmaker’s 1978 flight to France, Silver shows how this lack of legal resolution has affected Geimer as much if not more than the initial crime. The book’s third author, Judith Newman, supplies subsidiary information in a sometimes distractingly 19th-century novelistic style, voicing Geimer’s “Why Me’s?” not only in regard to 1977, but in 2009 when Polanski was detained by Swiss police while trying to enter Switzerland in order to attend the Zurich Film festival to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award. This arrest was made following a request by U.S. authorities that he be apprehended and returned to the United States. Put in “provisional detention” in a Zurich jail (where he managed by passing notes to his editor Herve de Luze to complete his film The Ghost Writer) and later under “house arrest” at his Swiss chalet, the Swiss released Polanski from custody, largely due to the disinclination of the U.S. courts to supply full documentation of the case. And it is at this point The Girl “begins” as Geimer, now fifty years old, married and with grown children of her own, feels now is the time for her voice to be heard because questions are sure to be asked again, and “So much has been written about the Polanski case but none of it has been written by me” and more tellingly “my story is just not pure awfulness.”

That’s most generous of Geimer, but in voicing it one wonders whose story The Girl is telling exactly. For there on the book’s frontispiece is a quote from Polanski’s Chinatown: “You see, Mr. Giddes, most men never have to face the fact that in the right time, the right place. . .they are capable of anything.” At the time of incident, Geimer says she “knew nothing “ of Polanski’s career. “I had seen Chinatown and didn’t like it, thought it was brutal and boring.” She then goes on to note that he’d made “my favorite movie at the time, The Fearless Vampire Killers.” That being the case one wonders why she didn’t recognize him when they were first introduced, as he was in literally every scene of the film she claims to be her favorite. Would it be ungenerous to say that The Fearless Vampire Killers, the comic horror satire starring Polanski and his late wife Sharon Tate, didn’t fit into to the picture the book’s authors are trying to create? Tate was, as everyone knows, hideously slaughtered along with several of the couple’s friends on the order of psychotic self-styled guru Charles Manson. While a success in Europe The Fearless Vampire killers had only marginal impact in the U.S. Chinatown, by contrast, was an enormous critical and commercial hit. Moreover, its dark tale of murder and municipal chicanery included father-daughter incest as well. In no way does Polanski depict this as copasetic. But The Girl seeks to link Polanski’s illegal dalliance with Geimer to his art. It’s therefore a bright and shiny object the authors can’t resist.

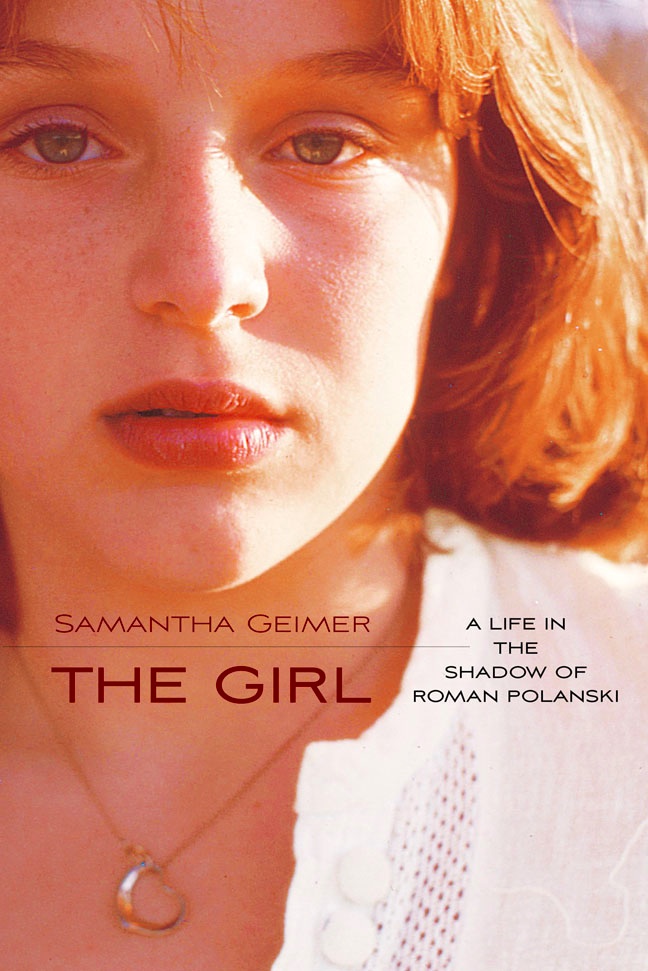

Likewise the book’s cover photo.

It’s an extreme close-up of Geimer taken, we are informed in an article published in the Hollywood Reporter , “less than three weeks before Polanski drugged and raped her at Jack Nicholson’s Mulholland Drive home during a modeling shoot when he also gave her alcohol and a quaalude” it bears no resemblance whatsoever to the other cheery photos Polanski took of Geimer during that infamous test shoot. But as Geimer isn’t smiling it serves to satisfy what can only be called prurient interest in that it’s a picture of ‘the victim” seen from “the rapist’s POV.”

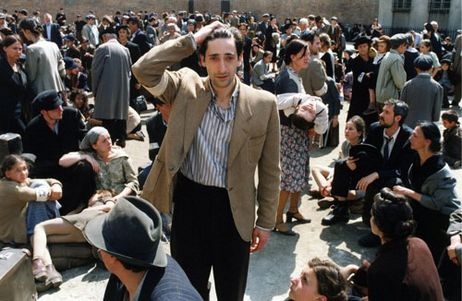

Again the rape was “statutory” in that Geimer was underage. “Not everyone will understand this,” she declares. “but I never thought he wanted to hurt me; he wanted me to enjoy it.” However such words mean nothing to those intent on unloading their scorn on Polanski, as if this wildly ill-advised episode were the essence of everything wrong with sexuality in modern culture, and the only thing worth talking about in a life that, in addition to the creation of such classics as Knife in the Water, Rosemary’s Baby, The Pianist and the aforementioned Chinatown, included the extermination of his mother in the Nazi ovens, his hairs-breath escape form the Krakow ghetto, living the better part of his adolescence as a hunted animal in the woods, and the slaughter of Sharon Tate and his friends at the early height of his Hollywood fame. All of this, you can be sure, will take a backseat to Samantha Geimer, destined to be mentioned in the very first graph of Polanski’s obituary.

“I don’t think I can overstate the shift in attitudes toward sex in the mid to late 1970s versus ten or even five years before,” says The Girl, citing Brooke Shields and Jodie Foster, the era’s most famous nymphettes whose success Geimer was well aware of. “Young girls are eroticized to some extent in every culture, and at this point in time in our own culture that eroticization had become almost mainstream.” She was well aware of her value in this regard as she was seeking a career. “I was cute. I had the head shots. I was going out on auditions and some callbacks.” Her sister Kim had been seeing a French producer named Henri Sera. He invited Samantha’s mother, Susan Gailey , an actress with several TV credits—though Geimer mentions only her work in print advertisements—to a party at the club Top of the Rocks where she met Warren Beatty and Roman Polanski. Geimer describes Gailey and the latter’s boyfriend Bob as “pretty much like every other unsophisticated aspiring actor in Hollywood.” But surely not so unsophisticated as to not realize the importance of meeting the likes of Beatty and Polanski—especially when learning of the latter’s interest in discovering young American girls for a Vogue fashion shoot. And it is here where Gore Vidal’s assessment of the situation, published in The Atlantic Monthly and quoted in The Girl, comes most dramatically into play.

“Back then, we all were. Everybody knew everybody else. There was a totally different story at the time that doesn’t resemble anything that we’re now being told,” Vidal claims, “Look, am I going to sit and weep every time a young hooker feels as though she’s been taken advantage of?” he declares with customary savoir faire. But as ugly as it may be to contemplate, there were good reasons for Vidal presuming this was the case. Hollywood has a long and ignoble history of “stage parents” eager to offer up their offspring to “celebrities” in exchange for fame, career and sometimes cold hard cash. The Girl denies this was the case each and every time this sinister specter is raised. She relates how Polanski showed her mother the Vogue fashion shoot with a Pirate theme he had devised for Nastassja Kinski—at that time not that much older than Geimer.

She claims she didn’t think much of “this brooding purse-lipped little man” but was far from averse to having him take her picture. While taking a few shots of her on her on a hill near her home she was not at all disturbed when he asked her to take off her top. “Breasts were beautiful, that’s what The Joy of Sex said, and I thought so. It’s just that I didn’t have them really.” Susan Gailey wasn’t invited to this or any of the other shoots—Brook Shields’ domineering mother Terri serving as an explanation for Geimer of what she didn’t want to spoil the occasion. That session was fairly simple. The next was on March 10 when, in Geimer’s words “It just happened.”

The first stop was actress Jacqueline Bissett’s house. “She was very nice and offered me a glass of wine. I said no. Later, she said she was appalled she had offered liquor to a minor—that she hadn’t known my real age.” In other words she seemed adult female—as the police report would later identify her. The photos taken at Bissett’s were “maybe the tiniest bit risque” with no indication of what that might mean in that they weren’t topless. Perhaps Geimer was recalling the drift of the conversation as Polanski asked if she had a boyfriend and if she had ever had sex. She answered yes to both, informing us, “I did not want him to think of me as a child.” A fortiori when he asked how many times she had had sex, she told him twice. She tells us that was a lie. But it was of course part of the aura of sophistication she wanted to create for him. “If he knew that I had seen Playboy before, he’d understand that I was quite mature.”

Then as the light was fading, they went to Jack Nicholson’s. And it is here the “plied her with drugs and alcohol” part of the story is fully explicated. “He pulls out a champagne bottle and asks me, ‘Should I open it?’ ‘I don’t care,’ I say, ‘Is that alright?’ he asks the housekeeper, and she pulls out three glasses.” The “housekeeper” is actress and producer Helena Kallianiotes, who according to the Internet Movie Database, is “A good friend of Jack Nicholson, for years lived in the guest house on his property and acted as his property manager whenever he was out of town.” Not a mere “housekeeper.”

Polanski takes her picture posing with a champagne glass and drinking from it. “He keeps refilling, but I try to pace myself. . . He tells me to change my clothes. I put on the long blue dress with the long sleeves.” He then calls Geimer’s mother, tells her what they’re doing and informs her that he’ll be driving her home soon. It is then that he shows her the Quaalude and asks her if she knows what it is. She says yes. He asks her if she thinks he should take one, then asks if she wants some of it. “He wants me to. So then I say yes.” And so we have “consent.” But is it “informed?”

Now it’s on to the Jacuzzi. “He asks me to get in: “You should take your panties off.” And then?

“Let me think back. Such excitement.” And it is here I suspect Judith Newman takes over, rendering the events a kind of PG-13 version of Justine ou les infortunes de la vertu . “I want out. How fucking stupid could I be? It’s a hard thought to hold onto. . .I knew this wasn’t right. But I don’t know what to do. . . He asks her if it feels good. There’s nothing good about it. . . Why don’t I say ‘No’? Why don’t I say ‘Don’t touch me’?”

Well that’s why we’re reading this book, isn’t it? She tells him she has asthma. “Why did I say this?” she asks us as usual. “He suggests I jump in the pool, that it will cool me down.” She does, then “zooms” to the other side gets out and goes into the bedroom.“ ‘I have to go home,’ I say but he takes me by the shoulders and walks me to the bedroom and sits me on a large velvet couch. . .. He’s kissing my face and feeling my breasts and he asks me again if I like it, does it feel good. I say nothing but he’s a guy who makes movies so I imagine he’s filling in the dialogue for himself. . Then he goes down on me I know what this is because I’ve read about it but have never actually had someone do it to me. He asks if it feels good, which it does—and that in itself is awful. . . my mind recoils but my body is betraying me. And that’s when I check out. . . he is trying to make it nice for me I know. But I don’t fight. Why fight? All he wants to do is have an orgasm. . . It’s just sex, he doesn’t want to hurt me. . .We are both playing our parts.” And apparently part of such “playing” is his asking her if she’s on the pill, when she had her last period, and if she wants to have anal intercourse. “I say, ‘No, but I don’t know what he’s asking anyway. . . When it happened I didn’t know what to think.” The question is when what happened? For as the doctors report later shows there was no evidence of anal intercourse—even though it’s presented as the piece de resistance of the entire encounter—a Last Tango in Beverly Hills as it were.

Anjelica Huston, then still Nicholson’s longtime girlfriend, shows up and Geimer heads for the car. “For some reason I didn’t want him to know that he had scared me and that I was upset.” For the very good and obvious reason that she hopes a professional photo shoot will result following these tests shots. “Is there anything you don’t want them to see?” Polanski asks her. “You can show them all,” she tells him—and that’s when disaster strikes. “He made me have sex with him. He made me do it,” she says to her boyfriend Steve, apparently the minute she gets home. However, “He didn’t really believe me.” Then they see the topless photos and freak out, but not too visibly because Polanski leaves without any confrontation. Plans are made to contact them at some other time as these test pics were NOT the shoot. Geimer says she “can’t remember” all that happened after that and then proceeds to recount it. The police are called. She’s questioned by detective Phillip Vanatter (later of O.J. Simpson fame) and examined at a hospital. And then she was asked to testify before a grand jury. “Going through grand jury testimony felt more like rape than the night with Polanski,” she says. And reading the transcript, one can see her point. The grand jury deliberated for less than half an hour and returned with six counts. And then we learn this: “In his autobiography, Polanski would write that at one of the hearings [District Attorney Roger] Gunson’s staff saw me and Bob—my mother’s longterm boyfriend, a man I considered another father—‘locked in a steamy, passionate embrace. It wasn’t the avuncular hug of a grown man comforting a young girl—it was more; her leg was between his legs.’ I read that and felt a little queasy. I did, in fact, sometimes regress with Bob; I remember sitting in his lap with my arms around him, at one hearing. But the implication of this. . . Did anyone really report that? Did they really believe it? “

Yes that’s it. We all “sometimes regress,” don’t we? And after a sexual experience this shattering we try to wipe it away with subsequent experiences as soon as possible, as Geimer did with a new boyfriend named John. “I was barely fourteen, and I suppose I should have felt guilty. I didn’t. I felt I deserved to wash away the bad experience with a good one, and John was the equivalent of a long hot shower.”

Yes, that’s what we all need in this life—a long hot shower. All we can hope for is it’s not taken in the glare of the spotlight that has engulfed Samantha Geimer. Not to mention Roman Polanski.