Born: December 5, 1901, Chicago, IL

Died: December 15, 1966, Los Angeles, CA

The whole success of the Disney operation was Walt’s demand for high quality.

—Ward Kimball

The entire first decade of Walt Disney’s career was extremely rocky. He had locked himself and his company into poor business arrangements. His studio wasn’t producing anything unique. The rubbery look of its characters was unimpressive, and the rival studio across town, headed by producer Max Fleischer, was making cartoons that were often more innovative. Still, Disney remained optimistic. His commitment and energy helped him become an industrialist whose product was entertainment and whose brand name stood for imagination. And today, “Disney” is a household word symbolizing the best of American values in family entertainment.

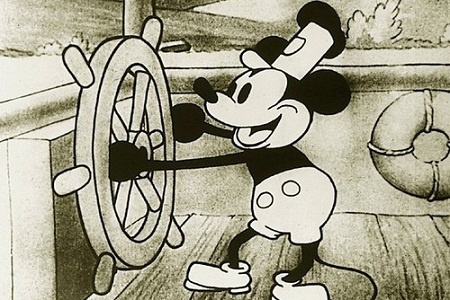

Throughout the 1920s, Disney’s sole effort was to keep his Alice in Cartoonland (1923-26) series alive. But after a brief year of Oswald the Rabbit shorts, Disney felt he needed an edge on other cartoon studios to make a name for himself. He told his lead animator, Ub Iwerks, to create an animated character that would capitalize on the coming sound era. Iwerks’s creation was Mickey Mouse. Originally scheduled to appear on the same bill as The Jazz Singer (1927), Mickey’s debut in Steamboat Willie (1928) put the Disney studio in the spotlight.

The sudden fame of Mickey Mouse forced Disney to shuffle responsibilities. A cattle call went out across the country for anyone interested in becoming an animator, and a flood of talented illustrators poured into Hollywood. Many of these people would be trained under Disney’s roof and blossom into some of the biggest names in animation. To meet his demands for improved quality, artists were asked to specialize in certain job functions. Disney wanted a team concentrated on technical improvements. He wanted a special effects department. He put animators through life-drawing lessons and brought live animals into the classrooms, all in a search for realistic motion. He asked the creators of Donald Duck, Goofy and Pluto to give their characters more emotions and vitality. Most of all, he asked everyone to contribute to story development.

An important by-product of Disney’s reorganization was the use of storyboards to plan a movie’s production. A storyboard is a series of individual pieces of paper, each displaying an illustration of a scene, outlining every action in a film. Pinned to a wall or mounted on an easel, storyboards became “picture scripts,” allowing groups of animators to analyze each scene long before committing ideas to ink. Simply put, the storyboard made Disney films great. It eliminated unnecessary work. It made writers a part of character creation. It kept stories focused on their themes. Breaking artists into different teams, Disney would have ideas developed independently before bringing a number of storyboards together in one room, where he could excise redundancies and smooth out transitions. The films created with this process were far superior to any other cartoons, and storyboards went well beyond animation circles. They are being used today in advertising agencies and television studios; among film directors, such meticulous planners as Alfred Hitchcock, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg have relied on storyboards to communicate their ideas to others and keep projects on track.

In spite of many critical successes, Disney continually struggled for profits. During World War II, his studio survived only on propaganda films made under government contracts. Disney’s deals to merchandise Mickey watches, dolls and shirts helped to stave off the effects of the Depression, until he could complete his company’s transformation. In 1931, he signed an exclusive agreement with Natalie Kalmus to use Technicolor on every film for a period of seven years. No other cartoon studio could use the three-color process, and Disney capitalized on the novelty of color with the majestic debut of Flowers and Trees (1932). As the end of this agreement approached, Disney feared other color cartoons would catch up to his quality. He hurried to release Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938) to further distance Disney quality from the pack and establish the studio as a feature film shop.

Although he would continue to produce theatrical shorts for many more years, full-length spectacles became Disney’s hallmark. The most important of these was Fantasia (1940), the marriage of a Leopold Stokowski-conducted score with abstract and experimental animation. A controversial film, it initially performed dismally at the box office. Classical music fans shuddered at the idea of hippos dancing all over Tchaikovsky, and common folks avoided its pretentious aim by simply staying away from the theaters. However, many years after Fantasia’s brief theatrical release, admirers begged Disney for another screening of the film. Haunted by the huge losses from his Pinocchio (1940), Disney was eager to squeeze every last dime from his features, so he agreed to a repeat showing. The re-release became the first of many, and the lesson learned from Fantasia would help the studio reap millions over the years. Soon, Disney would also discover the value of merchandising his entire stock of films and characters.

Beginning in 1937, Disney’s films were under the exclusive control of a fourteen-year distribution deal with RKO Studios. But in 1953, Disney freed himself of major studios by releasing his cartoons through his own distribution company, Buena Vista. Immediately, the cartoon king set out to see if he could expand his empire. Grossing $1 million with The Living Desert (1953), Disney proved that his name was marketable beyond animated shorts. This led to live-action TV programs in 1954, like the popular Zorro and Davy Crockett series. The Wonderful World of Color also became part of the weekly habit of television viewers. And the much anticipated Disney theme park, opened in 1955, quickly climbed the list of favorite vacation destinations.

Innovations in both animation and live-action technique were present in Mary Poppins (1964), a huge success that garnered five Academy Awards and became the last big film that Walt Disney would have a hand in making. But his studio would stand firm well after his death, continuing with feature-length films, television specials and eventually cable programming. The leadership of the Disney studio in the animation industry remained steady throughout the 1970s, but the future of animated films looked bleak until the breakthrough films Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Little Mermaid (1989) sparked renewed interest among moviegoers in Disney animated features. These films succeeded by returning to the strong storylines and songs that Walt himself had insisted on.

Like many giants of industry, Walt Disney overcame early failures, restructured his ailing organization, perfected key processes in manufacturing and excelled. The detailed storyboarding techniques he used in planning his films are a lasting contribution, used in almost every movie made today. His unforgettable characters are often an extension of his personal values; the image of Mickey Mouse has become a universal symbol of spirited optimism and goodwill. The logo signature of Walt Disney graces literally millions of products; however, the name now stands for more than merely excellence in animation. His competitive drive and unflagging standards set a benchmark for quality in family entertainment, and for more than half a century audiences have been eager to watch anything carrying his seal of approval.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.