Born: July 19, 1883, Vienna, Austria

Died: September 11, 1972, Woodland Hills, CA

Without Max’s pioneering spirit and additions to the technology of animation, few, if any, of us would be where we are today.

— Walt Disney

Like many animators in the cartoon industry, Max Fleischer began his career as an errand boy. Working alongside animation pioneer J.R. Bray on the Daily Eagle newspaper in Brooklyn, New York, in 1901, Fleischer spent his days punching holes in paper until moving up to become a cartoonist. In a prophetic step, the inventive artist with a passion for mechanical objects then took a job at Popular Science Monthly magazine, eventually quitting to join the ranks of artists who flooded the animation scene in 1915. During a brief World War I commission, Max was joined by his brother Dave to make instructional films for Bray. Together, the Fleischers and Bray would produce a bizarre and inventive collection of animated classics, and the technical advancements they discovered in making these films, primarily fueled by Max’s curious and competitive nature, would keep their films interesting and enduring.

The Fleischers made immediate waves with a popular series of animated shorts featuring Koko the Clown. The first of them, Out of the Inkwell (1916), earned them a contract with Paramount-Bray Pictographs for a regular supply of shorts; more than fifty were eventually produced. Brother Dave would soon take over the stories, supervising the development of such unique personalities as Betty Boop, Bimbo and Popeye the Sailor, a profitable cast that would afford Max a chance to branch out into other areas. These characters were among the first in animation circles to strike a chord with both moviegoers and fellow animators. Bray, Disney and other studio heads realized that strong cartoon personalities ensured steady work.

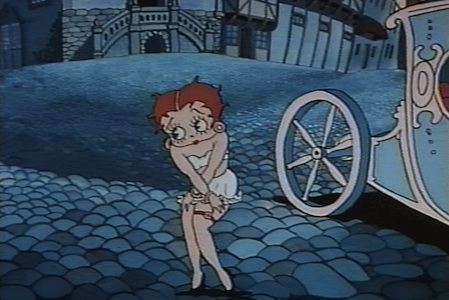

By 1920, the Fleischers were ready to start their own studio. The freewheeling animators of the Fleischer crew, such talented men as Ted Sears, Grim Natwick, Doc Crandall and John Culhane, demonstrated a highly experimental, surrealistic quality in their work that was more sinister, more racy, and much less rigid than Walt Disney’s output in this period; these early Fleischer classics include The Herring Murder Case (1931), Chessnuts (1932) and Swing, You Sinners (1930). Their interpretations of the slinky Boop as the quintessential flapper were never more seductive than in Mysterious Mose (1930) and Bamboo Isle (1932). These films were watched more closely by the Production Code censors of the Hays Office than any Mae West movie; in Bimbo’s Initiation (1931), a sexy Betty Boop sequence has her slapping her own buttocks coyly to lure a stray dog closer.

Although the Disney and Fleischer studios both pioneered the use of cartoons set to music, Fleischer’s popular Minnie the Moocher (1932), featuring the wailing Cab Calloway and Rudy Vallee, started a trend of setting animation to hit recordings. Later that year, animators, drew Betty Boop and Bimbo singing and dancing to “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” “Just a Gigolo” and Irving Berlin’s Broadway tune “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” These wildly popular musical shorts, the earliest examples of synchronized dance numbers, are the direct forerunners of today’s music videos.

Max himself stepped away from the drawing table early on to concentrate on the mechanics of the cartoon craft. Frustrated by the limitations of cel animation, he was driven by a dream of a more lifelike product. After extensive experiments with live-action films he struck upon the idea of filming actors in motion, then projecting the images onto paper and tracing them. The process, known as Rotoscoping, created smooth, realistic action that allowed illustrators to duplicate subtle human behaviors and predated the best efforts of Walt Disney by fifteen years. First displayed in Koko cartoons of 1916, the process is still used today in such animated films as Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Pocahontas (1995) and in video game production. Bray would call the process “super-animation,” but Fleischer simply explained it as the greatest achievement in pen-and-ink production.

Next Max dreamed up the Rotograph, a system by which live-action film is projected onto the underside of the artist’s table one frame at a time, which allowed animators to draw Koko among real New York skylines. The real world and the India-ink clown were then brought together in a single exposure. This ingenious method was a precursor to techniques used in Mary Poppins (1964) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988).

Fleischer was also an innovator in color animated films. He beat Disney to a three-color process with Somewhere in Dreamland (1936) but suffered when Walt signed an exclusive contract with Technicolor merchant Natalie Kalmus. With Technicolor tied up, Fleischer adapted a two-color process to compete. He also forged into the world of three dimensions, developing 3-D processes for Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s 40 Thieves (1937) and Gulliver’s Travels (1939) that were state-of-the-art and forced others to adjust their methods again.

A tireless tinkerer, Fleischer presented a steady stream of optical tricks of color innovations, and sound curiosities that baffled and delighted his peers. Had he focused on any one technology, his studio might have become more famous than Disney’s. Absent a distinctive style, the ever-changing look of a Fleischer cartoon became a symbol for the restless mind of Max. What his films lacked in consistent quality, they made up for in unexpected zaniness; he kept audiences entertained and competitors fearful. He had more genius than Disney but lacked the showmanship, the discipline, and, most important, the vision. Both men forged clear paths toward realism in animated films, but while Disney built upon each success, Max left behind yesterday’s innovations for the wonders of tomorrow.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ as well as the full list of the most influential people in the history of the movies, go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.