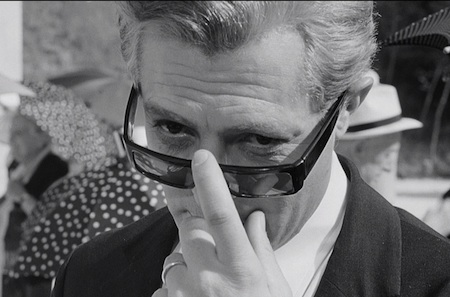

Born: January 20, 1920, Rimini, Italy

Died: October 31, Rome, Italy

I prefer cinema of lies, lies are much more interesting than truth.

—Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini had written scripts for Roberto Rossellini before coming into his own as a director of impressive films in the 1950s, when the form in vogue was neorealism, a rough-hewn documentary approach to giving films a more realistic feel. By the 1960s, Fellini’s work began to change and reflect a flamboyance that would mark him as a unique visionary. He was among the few film storytellers to document his entire life through his body of work. His films adopted metaphorical images, like Ingmar Bergman’s, but Fellini infused his movies with surreal sequences that did for cinema what Picasso had done for painting.

A onetime crime reporter and caricaturist, Fellini began his film career with original stories for Rossellini’s Ways of Love (1948). From scripting sympathetic characters, he advanced to directing startling performances with the powerful debut of La Strada (1954). Poetic and moving, it revealed Fellini’s ability to mix the grotesque with the sublime. Instantly, his name gained international attention.

Widespread acceptance of Italian films was achieved through La Dolce Vita (1960), which matched the depth of its story with striking and unforgettable images, particularly scenes of Anita Ekberg, the film’s sex interest, playfully kicking up water in Rome’s landmark Trevi Fountain. The reflective, intelligent drama about soul searching left an impression on young filmmakers, Woody Allen and Paul Mazursky prominent among them. It received overwhelming critical support and was a box office success despite condemnation from both the Catholic Church and the Italian government, which felt the film mocked religion and exploited the ills of society.

By the time the furor over La Dolce Vita died down, Fellini was lionized throughout the world. Unprepared for this sudden attention, he became paralyzed by the global fixation on him, began to feel suffocated by his creativity and struggled to summon the will to make another film. After months of reclusion, he resurfaced with a film that brilliantly made light of his own personal panic: 8½ (1963), an acerbic satire on celebrity status. With his demons behind him, Fellini forged ahead to Juliet of the Spirits (1965), his first color film. Like their predecessors, both films garnered unflagging raves from reviewers and fans, and Fellini was well on his way to legendary status as a filmmaker with a singular style.

By Fellini Satyricon (1970), depicting the bawdy adventures of pre-Christian bisexuals, the look of Fellini’s films had changed. His newfound signature featured absurdist humor and crisp, vivid images from extreme and unusual viewpoints. During this period, Fellini pushed the limits of his craft and set the tone for the bizarre fantasies with which he would be closely identified. His most fantastical scenes, featuring intense color, striking makeup and costumes, radical camera angles and a host of eccentric and outlandish characters, would soon show up in the dream sequences and nightmarish flashbacks of thousands of films by others. Such scenes prompted the coining of “Fellini-esque,” describing a collage of dream sequences which reflect real-life fears and paranoia.

As his work became less focused, Fellini indulged his own eccentricities to excess. There were some financial failures and critical disappointments before Amarcord (1974) reaped his fourth Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Unfortunately, his visions now required bigger budgets, and his sporadic box office returns scared investors away. By the 1980s, the damage was done: no one was willing to finance his surreal fantasies. He completed his last film, Voice of the Moon, in 1990 with his own money.

Fellini was awarded a special Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1993. As do the autobiographical films of Ingmar Bergman and Woody Allen, Fellini’s stories assumed a distinctive style that was marked by bold exploration of the human psyche. The day after his fiftieth wedding anniversary, he suffered a stroke and went into a coma at age seventy-three, never to recover. The legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa expressed the sentiments of film lovers around the world by telling a friend, “Fellini’s death has upset me; the idea that we will never again see a new Fellini film is unbearable.”

To read all the republished articles and see the full 100 Most Influential People in the History of Movies list from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.