Welcome to the first installment of “The Big Ones,” my new column on cinematic works that are at least three hours long, possibly quite a bit longer, and all available on home video/streaming. It’s called “The Big Ones” for a few reasons. First, I think it’s funny. (Remember Kirstie Alley, accepting an Emmy award and thanking her then-husband Parker Stevenson for “giving [her] the big one” over the years? What better way to pay tribute to towering masterpieces such as Satantango or Shoah than by comparing them to the phallus of a washed-up TV star?) But second, and more honestly and importantly, “The Big Ones” was a film series of very long films, programmed by Paolo Cherchi-Usai at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, back when I was living there in the mid-’90s. The very concept was extremely intriguing to me then—films categorized not by director or actor or nationality or even theme, but by length—and it’s obviously stuck with me.

It’s not just that long films, or very long films in some cases, are less likely to be screened than films with more traditional running times. We know this is true; just ask our good friend Harvey Scissorhands. Certainly in commercial terms it’s hard for unusually long films to find a place in theaters, for the simple reason that they generate less money for exhibitors. Even if, in an ideal universe populated only by Jonathan Rosenbaums, North American audiences only wanted to see films like Yi Yi and Eureka and the director’s cut of Margaret, exhibitors would still cry foul. Long films can’t play as many times during the business day as shorter films, so the very opportunity for tickets sales are drastically reduced when running times swell.

In light of this, very long films (contemporary ones, not historical ones—more on those in a minute) have tended to languish in distribution limbo. An acknowledged masterwork of world cinema like Béla Tarr’s aforementioned Satantango (seven-plus-hours long) didn’t have a U.S. distributor until over a decade after it was made. (Facets Films and Cinema Parallel circulated it to major cities as a repertory booking.) Sion Sono’s four-hour epic Love Exposure, which is quite a bit faster-paced and more accessible than Tarr’s film, didn’t receive a commercial release in the U.S. for four years after its production date, and a scant release at that. Some stalwart distributors, dedicated to promoting Film as Art no matter the cost, will take the risks and put long films in theaters. Romanian filmmaker Cristi Puiu’s disturbing, attenuated Aurora, from a few years back, is a recent example. The good folks at Cinema Guild bought it, and really got it out there. But mostly, if it’s not a Hindi musical or it doesn’t feature Orcs and Hobbits, the three-hour mark really is box office poison.

So this is part of why I conceived of “The Big Ones.” In some sense, there is an answer to the dilemma of “long film” and its lack of accommodation to commercial dictates. Home video: the great equalizer. Yes? After all, between DVD and Blu-ray and Netflix and VOD and online streaming, not to mention services like Fandor, the average consumer has a wider array of access to all sorts of difficult films (including long ones) than ever before. Before we rattle our noisemakers and give ourselves a parade down Main Street Cinephilia, however, one question remains. Do these options actually serve the films?

Think of it this way. Back when, say, Antonioni was shooting L’Avventura, he understood certain basic parameters of his medium, not only on the production but also on the receiving end. He knew that his viewers would see his images and hear his sounds in a theater, unfolding gradually in time within a darkened room on a giant wall. He could compose his long, slow shots as time assemblies that would be organized within the sensory controls of the theatrical space. There would most likely be no interruption. The sequence would generate a virtual space vis-à-vis its spectators. It was just assumed that a filmmaker could reorganize time, like one plastic element among many.

Peter Greenaway was already way ahead of himself. ‘The Falls’ is a modular hypertext, a film that yields multiple varieties of pleasure depending on whether you choose to let it engulf you (the ‘modernist’ text), front to back and wall to wall; or if you take charge of it, treat it as a series of passages or even—I can’t believe I’m about to use this word—’webisodes.’

But is that the case now? What does it mean to watch a film on video, or on a laptop? Well, it certainly presents a shift in the size orientation of the viewer to the object. We kind of lord it over films now. And one way we do this is by exercising the power of Pause. We can start and stop a film over and over again, breaking up our experience of the work as a total, coherent whole. This basic element of the apparatus, wholly assumed by filmic modernism, is now compromised. How can a film’s formal aspects come together over the course of five or six partial viewings? And how does this alter the very idea of thinking about film as a composition in time?

To put it another way, we now have more access to once-obscure long films than ever before. But are these the works to which we gravitate, among our myriad choices? Are these works suited to the unique demands of home viewing? (Phone ringing, kids yelling, the lure of unanswered emails….) The answer to this question, it seems, depends entirely on how, in this era of digital delivery, we’re prepared to understand cinematic time. Does it still demand to be treated as an integral whole, a single composed experience? Or can it be segmented, lopped off, stopped, started, rewound, sent back to the beginning months later when you never got back to that movie you started, etc.?

We talk a lot about the problematics of watching celluloid artworks as digital artifacts, but we seem to speak much less about the temporal plasticity of video. Back in the early ’80s, when VCRs first came out, there was talk of watching your favorite shows at a time other than when they were broadcast. “Time-shifting,” remember that? Here, we’re talking about an entirely different kind of shifting of time, one that is more Gilles Deleuze territory than that earlier shuffling of solid things around a still-sturdy grid.

How has “long film” changed in light of this problem? We understand that canonical “Big Ones” are likely to make unwieldy, but not insurmountable, demands in the home video era. You can turn off your ringer (I actually just typed “unplug your phone” just now—this should be an indication of the tragically mid-century subject position I’m mired in, and that I struggle to overcome!) —anyway, you can turn off your ringer and watch Abel Gance’s Napoleon, if you have the wherewithal to shut out the larger world. (This part of this issue, who has the privilege to attain uninterrupted contemplative time, has been on philosophy’s back burner, of course, at least since the Greeks, and hits a crisis point with Descartes’ Meditations. But I digress.) But in any case, the “Big (Old) Ones” are still there, with their high-modernist temporal frameworks, making no concessions to contemporary viewing conditions. Barring the lucky strike of a repertory screening, we either bend ourselves to the iron will of the text, or vice versa.

But more recent films, it seems, can take this conundrum—distraction, interruption, fragmentation, play/pause/rewind—and conceptualize it, imprint it on their very DNA. This isn’t true only of “Big (New) Ones,” naturally. A lot of these multi-character roundelays seem to court distracted viewing, and imply a kind of modularity. (“This couple didn’t test well in Orange County. Drop ‘em.”) But in a broader, more expansive sense, the digitization of time-based communication has had a number of structural consequences. The move to non-linear editing suites like the Avid system, the greater application of web-based narrative tools, hypertext, and even the increasing tendency to perceive a “film” (you know, the finite, time-based piece of story-strip) as one component in an expanded field of relay that includes the website, the tie-in books, and other platforms. (Back when I taught at Syracuse University, the Film department proudly rechristened itself the Department of Transmedia, as a kind of harbinger of all this stuff. Sounds vaguely Death Starry to me, but you know. “Unplug the phone.”)

But wait up. You’ll notice I used the word “structural” up there. I did so advisedly, because in a manner of speaking, that particular strain of avant-garde filmmakers, the so-called structuralists, already foresaw a lot of this movement toward “digital” data organization. As anyone in reach of the Criterion Collection’s recent Hollis Frampton set can attest, there was a guy who thought that Godard’s injunction—beginning, middle, end, not necessarily in that order—was kids’ stuff. Frampton films like Zorns Lemma and (Frampton’s really Big One) Magellan are structured like abstract information, catalogued like, well, data. Same thing with such structural “Big Ones” as Michael Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew or Ken Jacobs’ Star Spangled to Death. You can excise significant chunks from them; they imply many other elements that could be introduced into them. They are open texts. (In fact, according to Scott MacDonald, Frampton even stipulated that, in its finished form, Magellan should incorporate one of Yvonne Rainer’s own feature films. Among other things, this open taxonomic invitation would provide Magellan with the female perspective that Frampton, regardless of his every intention, could never provide.)

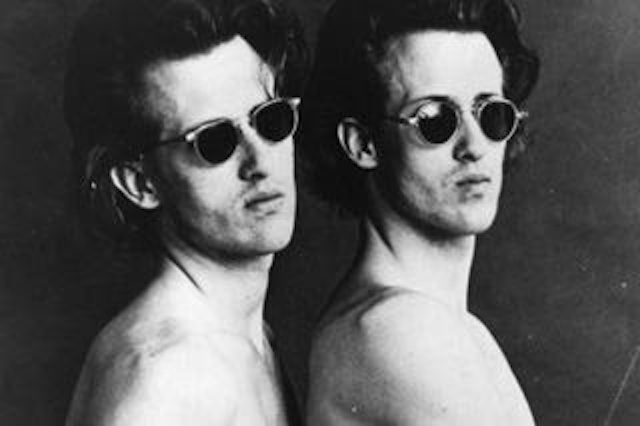

And of course, this leads us to Peter Greenaway and The Falls. In many respects, this three-hour semi-narrative, quasi-mockumentary, Borgesian-structuralist whatsit is the ultimate Big One for the age of digital viewing. Greenaway has long cited Frampton as one of his masters (along with Alain Resnais), although The Falls bears only passing resemblance to the work of either man. Part of what is so remarkable about The Falls is that this, of all places, represents the man’s first foray into feature filmmaking. Up to this point, Greenaway was making largely abstract films, editing experiments whose patterns mimicked the mathematical schemes of minimalist music (particularly that of his then-collaborator, composer Michael Nyman). Although two years earlier, in 1978, Greenaway had made the faux-documentary featurette Vertical Features Remake (in which he first introduced his lifelong alter ego, Tulse Luper), even that film was primarily about the organization of space in a much more classically structuralist mode (cf. Snow’s Wavelength, Ernie Gehr’s Serene Velocity), and building a narrative edifice around such experimentation.

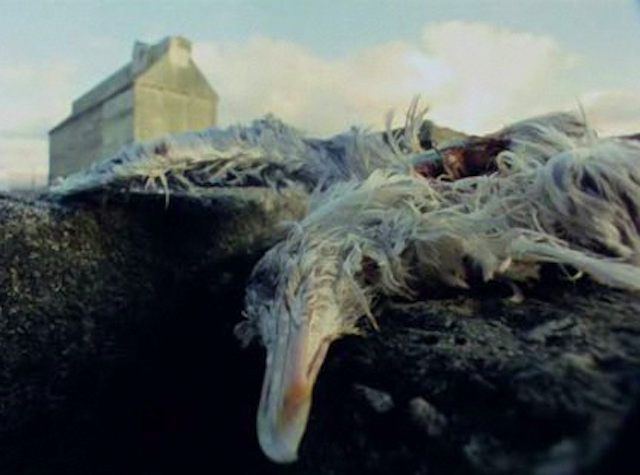

No, The Falls is a catalogue narrative, one in which 92 individuals are profiled. They have all undergone what the film mysteriously refers to as a Violent Unknown Event, or VUE. This event, never directly explained, has affected the individual so dramatically that in some ways they could be said to be mutants, or other than purely human. (Some are immortal. One can process saltwater. All develop new languages. Most develop some strange relationship with birds.) And, oh yes, they all have names beginning with the letters F-A-L-L.

In many respects, this three-hour semi-narrative, quasi-mockumentary, Borgesian-structuralist whatsit is the ultimate Big One for the age of digital viewing.

What does Greenaway want from us? There are several ways to think about this film—hundreds, really—but seen from the standpoint of Bigness, I’d like to propose just a few. First, the 92 subjects’ stories do eventually interrelate. However, this is only because the VUEs themselves paint a particular picture of a global scenario, one for which any given subject’s testimony is extraneous. This, after all, is how science functions. The “FALLs” are an implied random selection from a British Registry of several thousands of similar events. This means that The Falls, hypothetically, moves out almost infinitely, in both directions. Second, each of the 92 sections is alphabetically arranged. There is no “build” to The Falls, apart from that which accrues just by amassing multiple testimonies and profiles. That is to say, one could theoretically watch The Falls in many different orders and derive epiphenomenally different but essentially similar results. The Falls is a modular narrative.

So, the question of “The Big Ones” in the digital era: As I’ve mentioned, a great deal has been made of the radical changes that new technologies have produced in how we assimilate data, and how we balance and adjudicate between narrative and non-narrative information sets. Even Greenaway himself has gotten on this “transmedia” bandwagon, to mixed results. His Tulse Luper Suitcases project from a few years back encompassed three feature films, some video works, an interactive web presence, and was supposed to have included some graphic novels before the funding streams dried up.

But in many respects, Greenaway was already way ahead of himself. The Falls is a modular hypertext, a film that yields multiple varieties of pleasure depending on whether you choose to let it engulf you (the “modernist” text), front to back and wall to wall; or if you take charge of it, treat it as a series of passages or even—I can’t believe I’m about to use this word—“webisodes.” As this column progresses, we will see that not all “long film” has considered its post-film afterlife as thoroughly as The Falls has. Some are destined to suffer under the sovereignty of the remote control. But Greenaway’s foresight put his early cinema way ahead of where the medium would eventually exhaust itself.

The end, then strikes me as a perfect place for us to start.