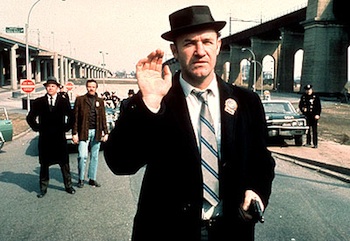

I came of age, cinematically and otherwise, in the 1970s. It’s a period now known as Hollywood’s Second Golden Age, and director William Friedkin was one of the hottest and brightest stars of the era. His breakthrough film, The French Connection (1971), totally revamped the American crime thriller and remains one of the few genre films to earn an Oscar for Best Picture (and one for its director, as well). His follow-up, The Exorcist (1973), was a cultural phenomenon and one of the most effective horror films of all time. Then came Sorcerer (1977), my favorite Friedkin film, as thrilling a piece of pure cinema as anyone made in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the film was a colossal critical and popular failure, one from which his career never fully recovered. Since then Friedkin’s résumé has included under-appreciated gems (The Brinks Job, To Live and Die in L.A., Bug), sturdy, straightforward entertainments (Blue Chips, Jade, The Hunted) and inexplicable misfires (Rampage, C.A.T. Squad, The Guardian, Jail Breakers). And still, 22 years later, he’s routinely asked to defend his sensational gay S&M thriller, Cruising.

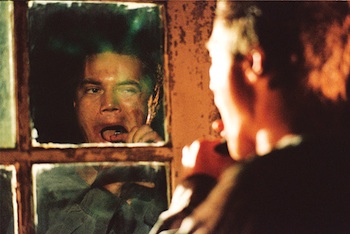

Killer Joe is the latest independently produced offering from the now 77-year-old director, and it feels like the brazen, energetic work of a young director having too much fun. I spoke with Friedkin in San Francisco on July 11, 2012, following a screening of the film the previous evening. As a famous villain once said, “I like talking to a man who likes to talk.”

Eddie Muller: So let’s start thinking about Sorcerer as a film noir and see if we can do something to get it—

William Friedkin: You know what’s happening?

Muller: I do know.

Friedkin: Well, let me give you the latest. I’ve sued Paramount and Universal because up until this year they allowed every organization that was legitimate to screen it—every university, film society, film club, the American Cinematheque, the AFI, Harvard, Cambridge, Oxford, other film enthusiast clubs that wanted to run it. They made a new print of it last year.

Muller: That’s good to know.

Friedkin: Paramount did. The two of them jointly own it.

Muller: 35mm? Or a digital restoration?

Friedkin: They made a 35mm print that was beautiful. It was last run at the Cinematheque, at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica. And after that, they [Paramount] started sending letters to a group called Cinefamily that wanted to run it, which has a huge subscription of film lovers, and Lincoln Center, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, who wants to run it in a retrospective. They sent them all letters, which would bounce to me from these organizations, saying ‘We no longer own the film, and we don’t know who does.’ And I said, ‘That’s not possible.’ So I called the guys I know who run these [studios], and they said, ‘Well, let me check it, we’re looking into it,’ and they couldn’t figure it out. The young lawyers who run these studios have no idea of the library, the legacy, or anything else—they’re just told to wrap up all 35mm, forget about all those film clubs and all that, let’s wean people onto digital, we don’t make any real money off of these screenings. So they sent these letters.

Muller: I’ve heard these very things; I know very well.

Friedkin: Sure. So, given that they put in writing that they don’t own the film and don’t know who does—I sued them with one of the best lawyers in Los Angeles. The suit is now in the Ninth Circuit to determine who owns it, to have them produce documents to indicate who the owners are. If they sold the film to, let’s say, a dentist in Des Moines—then tell me that!

Muller: And now the suit is against Paramount and Universal?

Friedkin: Yeah, I’m suing both of them. We’ve asked them for discovery, all the documents pertaining to ownership, and it’s part of my claim, saying, ‘Well, if you guys don’t own it, I must,’ because I’m a profit participant. And I want it, and I can get it released tomorrow—theatrically as well as on home video. So instead of simply settling, they’ve let it proceed. The presiding judge of the Ninth Circuit set the date of November of this year—November 26—by which to have a settlement conference, and end it before it ever gets to trial. And if that doesn’t happen, he has set it over for trial for on March 13 of 2013. And that’s where it stands. A settlement conference no later than the end of November, or a trial in March of 2013. And I don’t know—they may find some obscure thing in the law that says that they don’t have to tell me shit, but I am a profit holder. I’m not suing the for money—and that’s in my suit—I’m suing them for the right to have the film shown by whoever wants to show it, and in my complaint I’ve said that if any money comes to me from this, I’ll donate it to film preservation and restoration.

Muller: What a hero!

Friedkin: All of it, except whatever my lawyers want, and my lawyers aren’t looking to do this for money.

Muller: When I heard that you were doing this, it was incredibly significant because with the Film Noir Foundation I bang my head against this all the time: They just say, ‘We don’t know who owns that, or, we own it but don’t have a print, and don’t bother us.’

Friedkin: That’s bullshit! They have no respect for the industry that they’re in, and for its legacy—none. Look, Lincoln Center tried to get a print of Blade Runner from Warner Bros., and they got the same letter: ‘We don’t know who owns it.’ When the guy from Lincoln Center called me…

Muller: How long ago was this?

Friedkin: A few months ago.

Muller: This was Scott Foundas?

Friedkin: Scott Foundas called me and said that he also tried to get a print from Paramount of Phil Kaufman’s film White Dawn—you know Phil?

Muller: I do know Phil.

Friedkin: You live here, don’t you?

Muller: I do.

Friedkin: You know Phil. Well, he made a film called White Dawn.

Muller: I know it well.

Friedkin: Same letter: ‘We don’t own it; we don’t know who does.’ When Scott told me that, I said, ‘I know who owns Blade Runner, he’s one of my closest friends! Bud Yorkin owns Blade Runner because Bud Yorkin, the former television producer with Norman Lear—all those hit TV shows—he had made a few movies, and he and his business partner were the completion bond for Blade Runner. The film went 8 million over budget, which was a fortune at the time, and Bud and [Jerry] Perenchio got all the ancillary rights, including t-shirts, home videos, toys, and remake and sequel rights—so they own the picture now. And they’re planning a prequel with Ridley Scott. But Warners didn’t have the courtesy to say ‘Oh, this guy owns it.’ All the young lawyers up there wrote, ‘We don’t own it, and don’t know who does’—and I say fuck them. Really. Hopefully this will be a step in the right direction of ending that reaction for you and others.

Muller: There needs to be some kind of precedent set. It has to do with money in a weird back-ass way, because if it’s not a huge amount of money then they don’t care about it at all.

Friedkin: That’s right.

Muller: That’s the problem we face trying to restore the older films. Look, Sorcerer is a 1977 film—but you go back to the ‘30s and ’40s, and it’s impossible, and that stuff really is deteriorating.

Friedkin: Try to get He Ran All the Way or Force of Evil…

Muller: Both of those, thankfully, are saved, but there are others where a private citizen has to step up and say, ‘I’ll raise the money to save the thing—don’t give me a bunch of shit about rights entanglements while the film is rotting in your vault.’ I mean, it’s ridiculous!

Friedkin: Well, they don’t care if it rots now because 35mm is a memory.

Well, they don’t care—they’re shooting everything digitally. Eastman Kodak is out of business, and there’s no more 35mm going to be made by this time next year. It’s only for classics, only for reference. We’re in the digital world; 35mm has a death notice on it. That’s part of what this is: ‘We don’t want to issue these 35s anymore, it’s costing us money just to book the thing in and out,’ you know. That’s their position. I don’t know if I can pull it off, because the law is a very circuitous path, but it’s the only one I have.

Muller: You’ve got to save it in 35mm if you’re going to have anything to make the digital version from, right?

Friedkin: Well, they don’t care—they’re shooting everything digitally. Eastman Kodak is out of business, and there’s no more 35mm going to be made by this time next year. It’s only for classics, only for reference. We’re in the digital world; 35mm has a death notice on it. That’s part of what this is: ‘We don’t want to issue these 35s anymore, it’s costing us money just to book the thing in and out,’ you know. That’s their position. I don’t know if I can pull it off, because the law is a very circuitous path, but it’s the only one I have.

Muller: The law is where you buy it—somebody said that one time. (Laughs.)

Friedkin: Well, they also said that it’s better to know the judge than to know the law. (Laughs.)

Muller: Now I have to tell you this—this is kind of a surprise, my Sorcerer connection. I met you 36 years ago when you were cutting Sorcerer because I was a research assistant on a TV show called The Billion Dollar Movies, and you were interviewed because of The Exorcist, and you were cutting Sorcerer…

Friedkin: I don’t remember that. I’m sorry, I don’t remember that.

Muller: I don’t expect you to. I’m telling you this because I knew you wouldn’t remember! This is why it was such a big deal for me: you and [editor] Bud Smith showed me the bridge sequence from Sorcerer on the flatbed…

Friedkin: It was pretty impressive, wasn’t it? (Laughs.)

Muller: Are you kidding? It’s the most awesome sequence ever!

Friedkin: And we had to do all of that stuff, there was no CGI, no opticals—we had to do every moment that you see, even make the rain, and make it look like a rushing river!

Muller: And the match-cutting in that scene… I mean, the film has to be rescued just to show people: ‘Look at the match-cutting in this sequence—it’s unreal!’

Friedkin: Well, you’re very kind, Eddie. The thing is, I’m giving [the lawsuit] a shot. I don’t know if I’m going to prevail, but I’m going to go the distance, and I would go the distance for other films, because I’m only making films today because of the legacy, and other people are going to make films—or whatever they’re called in the future—because of the films that influenced them. Some of which, I know, will be my own—I know that.

Muller: Oh, absolutely.

Friedkin: No sense of being modest about it—I’ve heard from enough people who still value the films I made years ago. So that’s part of what I’m working for, and the ability of some other filmmakers to have their films preserved.

Muller: That’s fantastic. You were the King of Hollywood for a while in the ’70s, but how do you feel about the business now, and your place in it?

Friedkin: I don’t have a place in it. I don’t watch the new films today—I can’t watch comic books and video games on a movie screen. Can’t do it—I’ve tried. There’s occasionally a film that comes along, it’s usually an independent out of left field, like a film I saw recently Beasts of the Southern Wild. Have you seen that?

Muller: There’s a local [story in that]. Behn Zeitlin.

Friedkin: Is he from San Francisco?

Muller: It was partially funded through the San Francisco Film Society grant program.

Friedkin: And…Ken Rainin’s daughter [Jennifer] … do you know her? Kenny Rainin was a friend of mine, and he passed away. He was a multimillionaire philanthropist and his daughter put up a lot of the money for it, I understand. And then ILM mixed it for them for virtually nothing.

‘Stars Wars’ changed the game forever in the same year ‘Sorcerer’ came out. When ‘Star Wars’ came out, which every studio passed on, and Fox reluctantly took it and had no faith in it to the extent that they gave Lucas all ancillary rights. They had no faith in it, and he’s made billions on it.

Muller: Well, I totally agree with your assessment of current films, which is part of the reason why I really got such a kick out of seeing Killer Joe last night. It was great watching an old hand do a movie like this—it’s about the people, and it’s very exciting. Who needs CGI when you can see Matthew McConaughey and these people tearing up the screen?

Friedkin: Yeah, the acting is worth watching. I feel the story is very interesting with a lot of nice switchbacks. I’m just attracted to that kind of material—it’s edgy, it’s difficult, but it’s what I’m interested in. I’m not interested in these blockbusters; I’ve tried to watch them in Cannes. There’s nothing wrong with them, you know, the difference is just that I’m not with the zeitgeist.

Muller: Do you really believe that? Do you really think that’s there’s nothing wrong with them?

Friedkin: No, there is nothing wrong with them because people want to see them by the millions, all over the world. People want to see these films—I just don’t. I don’t criticize them, I don’t want to see them—they’re not for me. They are for a lot of somebodies—I’ll tell you that.

Muller: Do you think that people, teenagers at an impressionable age, who see these movies—what movies do you think they’ll be making? Because my generation saw your films, Coppola’s films, Scorsese’s films, and it inspired a whole generation of people to make what I thought were a lot of damn good films.

Friedkin: So did Star Wars. Stars Wars changed the game forever in the same year Sorcerer came out. When Star Wars came out, which every studio passed on, and Fox reluctantly took it and had no faith in it to the extent that they gave Lucas all ancillary rights. They had no faith in it, and he’s made billions on it.

Muller: Yeah, but that changed the business of Hollywood.

Friedkin: Well, but a lot of these kids watch The Avengers, and that’s what they want to do. CGI. Now, anything that a director can dream up can be achieved on a computer—anything.

Muller: And it leads to that ‘We’ll do this in post’ thing. And as I know you must agree with, nothing done in post is more exciting than if you actually capture it—like you were saying last night about spontaneity, actually capturing it in front of the camera. When the house falls on Buster Keaton [in Steamboat Bill Jr.] would it have been better as a CGI effect? No, it’s the fact he was actually standing there, and the house fell.

Friedkin: At the same time, if I was starting out to have a career in the business today it would be as a computer graphic artist—they are the new directors of film. They don’t need actors anymore. They have generated a three dimensional holographic Elvis. Pretty soon they will be able to create actors. They won’t need cameramen, they’ll do it on a computer. They won’t need stuntmen; they don’t need them now. They can show a guy flying through a plate glass window and they draw the window in later. Stuntmen are an endangered species. Projectionists are an endangered species.

Muller: (Laughs.) Tell me about it.

Friedkin: All the way down the line, and they’re not going to need actors.

Muller: Are storytellers an endangered species?

Friedkin: Without a doubt. You know, the stories today are either remakes or ripoffs or sequels. Period. That’s it. And I just have no interest in that.

Muller: So that’s what intrigues me about your relationship with Tracy Letts. Let’s talk about that. I enjoyed seeing a somewhat unique title at the beginning of the film: ‘William Friedkin’s film of Tracy Letts’ Killer Joe.’

Friedkin: I put that in—he didn’t have that contractually. I put that in because that’s what it is: my version of his story. The producers didn’t want to put it in, it’s of no commercial value to them to have that credit. So yeah, I put that on the screen because that’s the truth. He created this story and these characters.

Muller: And I appreciate what you have to say about the value of the script, and as a director, your belief in sort of getting out of the way and letting the actors do what they do in front of the camera.

Friedkin: It’s not an overstatement, that’s the way it works. Where you really have to direct is if you miscast the part and you have to try and make a silk purse out of sow’s ear. If you get the wrong actor—I’ve been in that situation a number of times—that’s when I’ve had to direct my ass off. But that doesn’t make it work. It just means you work harder.

Where you really have to direct is if you miscast the part and you have to try and make a silk purse out of sow’s ear. If you get the wrong actor—I’ve been in that situation a number of times—that’s when I’ve had to direct my ass off. But that doesn’t make it work. It just means you work harder.

Muller: And how do you do that?

Friedkin: Well, you have to show them exactly what you want them to do, and give them line readings and all kinds of shit like that, which is counterproductive to believability on the screen.

Muller: So I was amazed—20 days to shoot this picture.

Friedkin: Yeah. I could have done it in 40 days, but it would have been the same film.

Muller: And seriously, no rehearsals at all?

Friedkin: No. With rehearsals you leave it on the rehearsal floor. It’s not true of a play—you have to rehearse to the point where you have the timing right. They learn the lines as they rehearse. They’re doing a whole play from beginning to end. Where in a movie you’re doing scenes at a time. Sometimes you’re doing ten seconds at a time, maybe two minutes at a time. But not the whole thing, beginning to end. So you just have to perfect those ten seconds and two minutes by making them real. That’s what perfect is to me—a feeling of reality, a sense of reality.

Muller: And with this movie there’s the question of tone, because it’s really difficult subject matter. Do you think about how the audience is going to react to something? Do you care?

Friedkin: I hope they react well. I hope the critics react well. I’ll explain to you what I feel about audiences and critics. How can I put this? If you get a good review from a critic it’s like a stranger who you run into at a coffee shop or on an airplane or something, and they say, ‘Hi, how are? I’m Ed Muller or Bill Friedkin,’ and it’s a lovely feeling that you carry with you for the rest of the day. If they are hard-ons, or you get a bad review, it’s the equivalent of watching your son getting heckled on the soccer field—it ruins your fucking day, and maybe the whole weekend. That to me is the difference between a good review and a bad review. That’s all. There are some people I know who are suicidal with bad reviews, but really, after all these years that’s what it amounts to for me. Same with audiences. I was in the theater last night for about the last minutes five or six minutes of the film, and the audience was roaring with laughter.

Muller: That was a good crowd. They went with it.

Friedkin: And every crowd I’ve seen goes with it. In Venice, in Toronto, in Austin, Texas, in Paramus, New Jersey—I didn’t go to all of those places, but others connected with the film did. In Brussels, Belgium, I was there at that screening with an audience of basically Comic-Con dudes, and they got the film totally—and it was translated. So they reacted in the same places in all of these venues. In Seattle, in London—I don’t know if you’ve seen the reviews for those places, but they’re largely great—80, 90, 94 percent, amazingly favorable. So that’s the feeling of … ‘Hi, how are you?’

Muller: Well I think you pull off something really difficult in this film, finding a tone that balances black humor with extreme sex and violence.

Friedkin: That’s good. I have to write an article for the Landmark Theater—they like the directors to write a letter.

Muller: Because what it reminded me of more than anything else…

Friedkin: That’s good—thank you. (Writes note to self.)

Muller: I’ll give you a better one: ‘Redneck Grand Guignol,’ that’s what this film is. (Laughs.) You realize that this is just going to keep going—it’s going to escalate and just get crazier and crazier, and you can’t do anything but laugh with it, you just have to give up.

Friedkin: It’s absurd. Totally absurd.

Muller: But it’s so hard to balance that, it’s hard to keep the audience and not lose them. So I mean, you say that the director just gets out of the way, but no.…

Friedkin: Oh no, you do that with the actors, but the most important thing a director does is put it together, maintain that tone. How it goes together. Because even if the spontaneity is there, and the story is clear, whatever it may be, and the performances are great—you can either enhance it in the cutting room, or destroy it. Both are possible. Unless it gets the TLC it needs; it’s like when you write something, an article, a book, whatever. It’s how you edit it. Everything is raw material for the editing, everything—all your research, all your knowledge is raw material for when you take it and edit it. And that’s never more true than in the editing of a film. That’s where it comes to life or when the life gets choked out of it, which is why I basically do my own editing. I work with an editor who is very creative and gives me a lot of ideas, and makes an enormous contribution, and a contribution technically. He’s more than a pair of hands. But it has to be my call—because that’s the movie.

Muller: And the editor on this … ?

Friedkin: Darrin Navarro. Now, I’ve worked with a number of them—Bud Smith on a lot of pictures, I’ve worked with a guy named Augie Hess, Darrin. I’ve worked with Tony Gibbs on The Birthday Party, he won the Academy Award for Tom Jones. I’ve worked with good editors and worked with bad editors, guys who tried to bring their own sensibility and impose it on the film.

If you get a good review from a critic it’s like a stranger who you run into at a coffee shop or on an airplane or something, and they say, ‘Hi, how are? I’m Ed Muller or Bill Friedkin,’ and it’s a lovely feeling that you carry with you for the rest of the day. If they are hard-ons, or you get a bad review, it’s the equivalent of watching your son getting heckled on the soccer field—it ruins your fucking day, and maybe the whole weekend. That to me is the difference between a good review and a bad review. That’s all. There are some people I know who are suicidal with bad reviews, but really, after all these years that’s what it amounts to for me. Same with audiences. I was in the theater last night for about the last minutes five or six minutes of the film, and the audience was roaring with laughter.

Muller: I’ve sensed a bit of skepticism in your remarks about the auteur theory. Having been somebody who believed it, then directed films of my own and learned what’s involved, it’s like, ‘Wow, there’s a lot of people with misconceptions of how movies get made.’ Can you espouse a little on the director’s role in the creation of motion pictures?

Friedkin: The auteur theory is valid in many cases. Let me modify that—in a handful of cases. There’s a single intelligence that informs a Fellini movie even though he’s had many writers. Sometimes three or four or even five writers get credit for the screenplay. A guy called Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and others are on the screenplays of his greatest movies. One intelligence informs Antonioni’s films. Stanley Kubrick based his films on the material of others. The Shining is a Stephen King novel, his version of it, Anthony Burgess wrote A Clockwork Orange, Jim Thompson and Calder Willingham wrote the screenplay for Paths of Glory—all kinds of people—Nabokov wrote Lolita, Barry Lyndon is from a Thackeray novel. But they’re Stanley Kubrick films, there’s no question that his approach, his vision of these films is what prevailed. But in most cases, guys with reputations as auteurs because it says ‘A Film by Joe Schmuck’ or Michael Mann or whoever the fuck it may be—it’s a film by about 150 or 200 people who contributed mightily. And if they were directed by someone else they might have been more or less effective. But there is only a handful of people whose imprint is so strong that their intelligence informed those films. 8 1/2, Citizen Kane, even though Herman Mankiewicz wrote as much of the script as Welles, it’s an Orson Welles movie! Hitchcock, he never wrote; he did rewrite a number of his scripts, but there were other writers. A guy wrote the novel of Psycho, Robert Bloch, and another guy wrote the screenplay…

Muller: Joseph Stefano.

Friedkin: There had to be something in that screenplay that got on the screen, but it’s an Alfred Hitchcock movie. As is Vertigo. It’s his obsessions, Fellini’s obsessions with big-titted, big-assed women, Antonioni’s obsessions with the distances between people and the places in which they move—all of this stuff comes from their intelligence. Ninety nine percent of the movies that come out that say ‘a film by’ this guy or ‘a production by’ that guy—he’s one of many craftsman that worked on it. No less important, perhaps a little more important, but not totally responsible.

A guy sits down in front of a blank paper and writes ‘Lolita, light of my life, flower of my loins. My sin, my soul. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.’—I mean, a guy sat in front a blank piece of paper and put that down, you know. And he created the fucking thing. Another guy stood in front of an empty canvas and made The View of Delft, a guy named Vermeer. Another guy stood in front of a blank wall—a blank wall!—in a monastery and drew and painted The Last Supper. OK? That‘s ‘a painting by,’ ‘a novel by,’ ‘a whatever by,’ but most of those ‘film by’ credits are bullshit—they were done by a three-ton pencil! There was six thousand pounds of contributions to those films. That’s my bottom line, and it’s true of many of my films. I chose the subject.

Muller: Is there such a thing as ‘a William Friedkin film?’ I mean, it says that on a lot of your films—

Friedkin: No! I didn’t want to take that credit. Bill Blatty forced me into it because he wanted it to say ‘William Blatty’s The Exorcist’ after we had agreed we weren’t going to have any titles on the film. We both sat down and said ‘Look, anyone who goes to see this movie is going to know the name of the movie that they have come in to see. They’re not going to wander in off the street, ‘I wonder what’s playing over here!’‘ You know, at the time, three bucks. ‘I wonder what’s in here. The Exorcist… what the fuck is this?’ They knew what they were going to see, why should I put a title at the beginning of it? I wanted no title, just the beginning, and then Bill got cold feet and said, ‘This is my big novel, I’ve got to this and that…’ And because the Director’s Guild says that the director’s name has to be first, the titles read ‘A William Friedkin Film’ first, ‘William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist