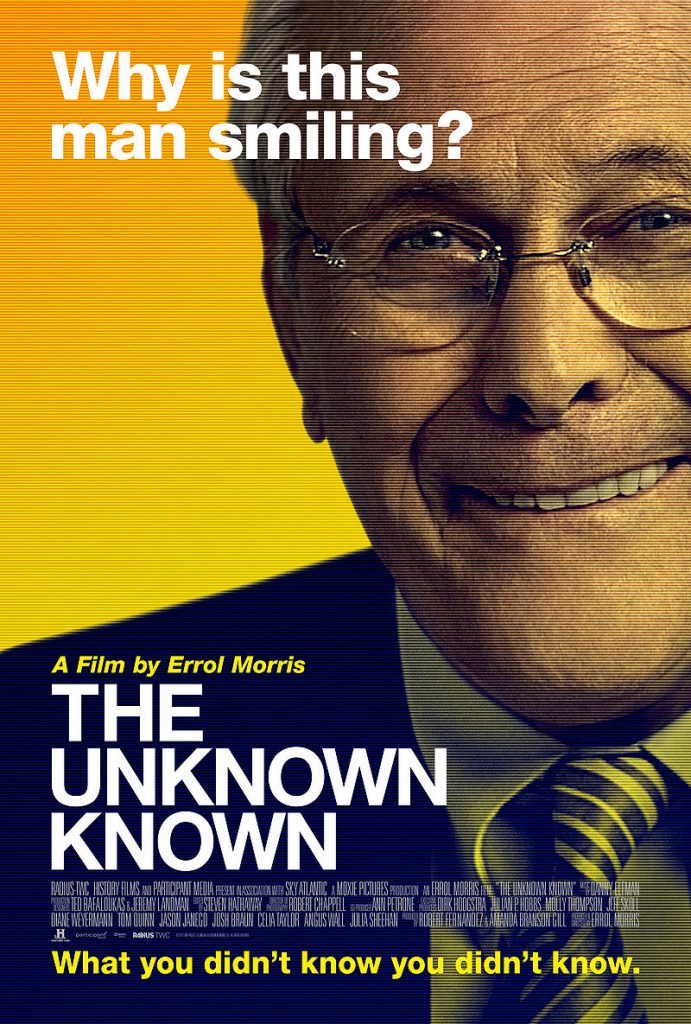

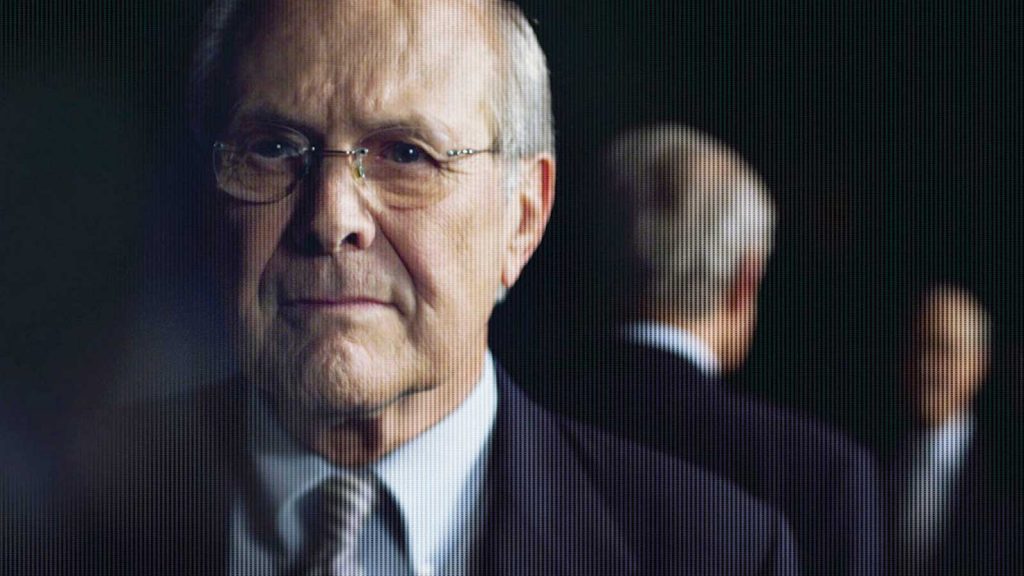

There is no definitive antonym for “hagiography” but such a word (if it existed) would be appropriate for The Unknown Known, Errol Morris’ portrait of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The film documents the early political life of Rumsfeld, first as a congressperson in the 1960s (representing his home state of Illinois) through him troubled (and troubling) time in the G.W. Bush administration. Known for his candor (for better and worse), Rumsfeld ruminates on many facets of his career, not least of which are his ‘snowflakes,’ numerous memos on a variety of topics. Morris gets Rumsfeld to read many of these aloud and these writings form a narrative (and occasionally visual) thread that carries the documentary along.

Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow spoke with the filmmaker at the Telluride Film Festival in September.

Jonathan Marlow: Inevitably, people will compare The Unknown Known with The Fog of War.

Errol Morris: Yes. I think that is inevitable. Although, as I tend to point out, The Unknown Known is far more like my previous film, Tabloid, than Fog of War.

Marlow: You mean insomuch as both feature a subject who is in complete denial of what they’ve done?

Morris: How could you say such a thing?

Marlow: But that is not the connection that most audiences would make.

Morris: We have to dispossess them of that notion.

Marlow: The obvious difference can be found in the subtitle to The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. There are no lessons that are learned in The Unknown Known.

Morris: There is one very significant lesson. When I asked about the possible lesson he learned from the horrible end of the Vietnam War, he said that the lesson is, ‘Some things work out, some things don’t.’

Marlow: Fair enough. That is a disturbing lesson to learn. Though it doesn’t seem as if he has learned that lesson. Or any lesson, really. It’s an acceptance of the fact that certain things, regardless of how well you want them to go or how much effort you put into them, will go poorly.

Morris: Of course, I include the famous press conference where he says, ‘Stuff happens.’ I asked him, after he does this very odd thing with respect to the [Arthur] Schlesinger memo, he denies that these techniques migrated to Iraq and Afghanistan. After I read him the memo, he said, ‘I would agree with that.’ But, in fact, the memo has just contradicted everything that he has said previously. Then I say to him, ‘Are you saying stuff just happens?’ He says, ‘Well, in war… ’ Basically, he says, ‘Yes.’

Marlow: Which is… troubling.

Morris: Troubling?

Marlow: I’m trying to soft‑pedal. In a sense, he is representative of an entire administration and its efforts at deception. He was just the most…. In a sense, Rumsfeld is the most obvious in his use of language to create a particular effect. His pedantic use semantics, primarily. He’s using language in entirely inaccurate and inappropriate ways. Changing things on a whim, notable in the discussion that forms the title of the film. He inverts his own definition for the combinations of ‘known’ and ‘unknown.’

Morris: Yes. I had a screening at MIT and a mathematician came up. This was just before we finished the film. I had rough‑cut screenings and they said, ‘A lot of what he says is a contradiction. It’s P and not P,’ and I said, ‘Yes. Yes, I know.’ Then they went on to say, ‘Well, from a contradiction, you can prove anything,’ and I said, ‘Yes, that also has occurred to me.’ There’s a kind of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ quality to it. My wife—the smart one in the family—said McNamara is the Flying Dutchman, traveling the world, searching for redemption and never finding it. Maybe he thinks he’s found it but I don’t think he’s found it. I think he remains as tortured as ever. Rumsfeld? The Cheshire Cat. All that’s really left at the end is a smile.

Marlow: Right. The grin.

Morris: The grin.

Marlow: The grin-without-a-cat. And that grin, it is a tic. It is a very strange thing that he does….

Morris: I think it is more than a tic. I think, often, it is a look of supreme self‑satisfaction. It is the look of the cat who swallowed the canary.

Marlow: Right. He knows that he’ll never be held accountable for his actions.

Morris: For example, when I say to him, ‘I assume it was Dick Cheney who got you the job the second time around as Secretary of Defense?’ He says, ‘One thing is for sure. It wasn’t George H. W. Bush.’ Then he has this really big smile. It goes on and on and on.

Marlow: Even though, earlier in the film, he denies orchestrating [G.H.W.] Bush’s move into the CIA.

Morris: People do not do things in government for Machiavellian reasons. They’re all bound by high‑minded principle.

Marlow: Of course. Absolutely.

Morris: I can see that you’re coming to this with a very, very bad attitude.

Marlow: You may be right about that.

Morris: You read the memo to Condoleezza Rice?

Marlow: Yes.

Morris: That’s high‑minded. Basically, ‘If you continue to assert your opinion, I’m just going to have you closed out. I’ll have you muzzled like a dog.’

Marlow: She was not a part of the…

Morris: …chain of command.

Marlow: Quite astonishing. How did this even come about? You have thirty-three hours of material, interview footage with Rumsfeld.

Morris: That’s correct. It could’ve gone on longer. Listen to this. You’ll like this. Two stories that I’m very fond of.

Marlow: Two stories. I’ll listen.

Morris: I live in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Marlow: A very beautiful place. If you must live in this country, that would be one of the places I would recommend.

Morris: I love Cambridge. A close friend of mine, who is the chairman of the film department at Harvard—I call it the junior college down the street—had a student who was making a movie about Duke Ellington. They started filming in the morning and Duke Ellington was wearing a dark jacket and then he came back after lunch wearing a canary‑yellow jacket. The student said, ‘But sir, there’s continuity.’ Duke Ellington said, ‘What do I care about your continuity? I’m ‘the Duke.’ ’

Marlow: Hard to argue with that.

Morris: We picked out a tie and jacket for [Rumsfeld]. If you look carefully, it’s not always the same jacket. The deal was that he would come for two interviews over two days. He could stay as long as he wanted each day. ‘Give me at least two or three hours.’

Marlow: He does like to talk.

Morris: Oh, yes.

Marlow: He does seem to enjoy the sound of his own voice.

Morris: I said, ‘I’ll edit it and I will send it back to you. If we sit here before we do anything and try to negotiate a contract, this movie will never happen. You’ll come up, I’ll interview you, I’ll edit it and—if you like what you see—we’ll sign a contract and we’ll continue and we’ll make a movie.’ I get on the phone with him a couple months after I’ve sent him the edited material and he says, ‘I have something to tell you, Morris. There’s something that just hasn’t worked out here.’ I think it’s all over. This is simply not going to happen. Then he goes on and says, ‘I just don’t like the tie I was wearing.’ I say….

Marlow: The tie was going to derail the conversation?

Morris: He asked me if he could change the tie and I said, ‘Yes, it’s possible. It would be extraordinarily time consuming and costly. Anyway, I like the tie. ‘ Nothing wrong with the tie. Do you like the tie?

Marlow: It’s a very nice tie.

Morris: See! There you go.

Marlow: It’s very nice. Yellow. As ties go, it’s very becoming. You picked a good tie. If you picked it, that is. Maybe your wife picked it.

Morris: My producer picked it.

Marlow: I wanted to figure out why… It is actually addressed in the film and I do not want to ruin that moment because it is handled quite beautifully. But it is the question that would be (or should be) on nearly everyone’s mind in the audience: Why would he submit himself to such questions?

Morris: Yes.

Marlow: He obviously believes that he has answers that supersede all other answers. That he can make the case, he’s above reproach on some level. The flip side of that is that some audiences will say, ‘You’re too kind to him.’ Of course, you could be a bad filmmaker. That would be the alternative. You’re not a bad filmmaker and you say something confrontational and then the whole conversation ends. You do want to have a film out of this. You want to have a conversation. You do allow him the opportunity to say all of these pretty idiotic things, which he seems incapable of recognizing, but he says them. He also says things in your interview that you refute in other things that he said elsewhere, whether they be the so‑called, ‘Snowflakes,’ other interviews that he’s done, or press conferences. I think the memory is fresh and anyone who’s politically engaged…before you even validate the fact that what he’s saying isn’t true, we remember because those are pretty visible moments. He was very actively in denial about the existence of weapons in mass destruction or the possibility of them being there. They were absolutely there and now that they weren’t there, that’s irrelevant. Many great things happened as a result of that activity. Why would he…did he…

Morris: I say to him, ‘Maybe we shouldn’t have gone there at all.’

Marlow: He doesn’t seem to think that that was even a possibility.

Morris: Time will tell.

Marlow: Time will tell. But time has not told. In the notion that as some magical period in the future, Rumsfeld will be vindicated? Is that the idea?

Morris: He says that when he is going out the door, after his farewell speech, Bush pats him on the back like he is dismissing some overpaid baseball player. Rumsfeld says that he’s sure that history will record. He doesn’t say that history will approve. He just says that history will record. ‘I’m sure that history will record what you’ve done.’ I certainly hope so, sir.

Marlow: This film does that, basically. An important documentary on an elusive group of snake-oil salespersons. This is an important film of its time.

Morris: Thank you.

Marlow: It’s something that I think needed to happen. Fortunately, you’ve done it. They sit before you and tell you what they’ve done, or he, in this case, Don Rumsfeld. I have never sat and spent hours and hours interviewing Dick Cheney. I get the feeling that Dick Cheney doesn’t really care what other people think.

Morris: I don’t know that for sure. That’s my hunch. Donald Rumsfeld does. That is a big difference between the two of them. It is interesting because you get these layers of the appeal to the public, the appeal to history, the self-deception.

Marlow: He claims that he’s well read about history, yet that seemingly has proved to be unhelpful to him.

Morris: I don’t know how well-read he is about history.

Marlow: He seems to believe himself to be a scholar of the American political system and well-versed in where he fits into that legacy.

Morris: There’s so much material we accumulated that I just simply couldn’t put in the movie. It’s just unfortunate. Maybe I’ll do something with all of that.

Marlow: Yes. That would be interesting.

Morris: There’s a whole section of his days at Princeton, his senior thesis at Princeton, his work on the wrestling team (in high school, college and then in the Navy.) He was very close to being in the Olympics. The fact that he’s a little short, which is also interesting because he makes these strange references to height even when he’s talking about checking out the safe in the chief of staff’s office.

Marlow: Correct. Yes.

Morris: He talks about my deputy, ‘Dick Cheney,’ and goes like this with his hand like he’s patting a dog. Or he makes this addressed when he becomes secretary defense under Ford and says, ‘I’m not saying the Russians are ten feet tall. I’m saying the Russians are five-feet three-inches and now they’re five feet eight.’ They’re growing. ‘

Marlow: It’s a very odd analogy. It’s very strange. He’s fixated.

Morris: I always worry that people will not understand how deeply crazy my movies are. I really do.

Marlow: Really?

Morris: I wrote down a list of my paranoid or not so paranoid fears about what people would say about this movie.

Marlow: It’s kind of a preemptive strike?

Morris: It’s self‑protective. I didn’t hand it out as a list to everybody. One: ‘There’s nothing new here. We’ve heard all of this before. Fuck you, Morris.’ I wouldn’t give you all of them. Two: ‘He doesn’t reveal anything. You didn’t learn anything from this man.’ Three: ‘You didn’t press him hard enough, did you? You didn’t really go after the goods, you little chicken shit,’ and on and on. The dialogue that goes on in my own tortured head.

Marlow: I suppose on some level there will be permutations of that which will surface in various critical assessments of this in the same way people had issues with Tabloid. All too often when people are making critical assessments of films, they’re not looking at the film that they’re seeing. They’re imagining the film that they wish was in front of them instead. That’s always a mistake.

Morris: Can I quote you?

Marlow: If you wish. It’s really infuriating. I saw Tabloid in Toronto and the wide range of impressions that people had about the film was surprising. Some claims of what you had ‘done’ to the subject. Which was nothing, really. You gave her an opportunity to tell her story…

Morris: Self-serving of me to say so but I think that I tried to make her look better rather than worse.

Marlow: I think you’re right. And then she went around the country to unravel that as much as possible.

Morris: She did, indeed. She’s still suing me.

Marlow: That doesn’t surprise me. That’s unfortunate.

Morris: She’ll be suing me forever.

Marlow: Since we’re here in Telluride, we need to discuss the apocryphal beginning of your career and how it gets told over and over again. I can think of no other documentary filmmaker that has an ‘origin story.’ Therein, I guess that makes you a ‘superhero’ of documentary filmmaking. All of these years later, what do you think about the relationship with Herzog, relationship you have with Tom Luddy, the experience of coming to Telluride, Europe to here. I do have to say that your talk with Geoff Dyer last year was a highlight. It was fantastic.

Morris: Really?

Marlow: Really fantastic.

Morris: Did you read the piece ‘The Murders of Gonzago’ that I wrote about Josh Oppenheimer’s film [The Act of Killing]?

Marlow: I haven’t read it yet.

Morris: I’ll send it to you if you’d like.

Marlow: I would. I spoke with Josh when I was in Austin. I met him here [at Telluride] last year and then we met up again in Texas. I was aware of your article, regardless.

Morris: I think it’s one of the better things I’ve written.

Marlow: All of your New York Times series are fascinating. Basically a variation—in written form—of your films.

Morris: Yes and no.

Marlow: You work in a very similar way whether it is a film or an article.

Morris: I have a third book [The Ashtray] forthcoming.

Marlow: I saw that on your ever-growing list of accomplishments.

Morris: As I said at the beginning of the screening at the Herzog Theatre, I thanked three people that made an enormous difference in my life. It’s not me just saying it. It’s true. It’s Werner [Herzog], Tom [Luddy] and Roger [Ebert]. The movie is dedicated to Roger.

Marlow: Which I think is a wonderful gesture.

Morris: I love Roger.

Marlow: There’s really nobody like him.

Morris: There’s nobody to ever replace him.

Marlow: Exactly right.

Morris: I used to joke with him every time I finished another movie, ‘How much less will you like this movie than Gates of Heaven?’

Marlow: It’s difficult when you start up at the top.

Morris: Yes.

Marlow: In the estimation of someone whom you really respect. You can only be discovered once.

Morris: I said to Werner—and this is true— ‘I have no memory of this claim.’ None. None whatsoever.

Marlow: That’s what I thought.

Morris: It does make for a good story. I said to Werner, ‘I’m a filmmaker in good part because of you, not because you ate your shoe or said that you would eat your shoe. I saw your films at the Pacific Film Archive.’ The tradition of documentary that I come out of isn’t [John] Grierson. It’s Fata Morgana. It’s Land of Darkness and Silence. Was he an enormous influence and does he remain an enormous influence on what I do? Of course he does. Fuck the shoe eating.

Marlow: Of course, it has been canonized through Les Blank’s film [Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe].

Morris: Yes. I wouldn’t come from New York to Los Angeles. I didn’t want to be a part of it. I sat at Kennedy airport and I was about to get on a plane and I just couldn’t do it.

Marlow: Really?

Morris: That’s correct. I just simply couldn’t do it. I’m probably not as charitable as I should be. I should just go along with it. What’s my problem? Free publicity.

Marlow: However, I think many more people arrived at your work through Roger Ebert’s review of The Thin Blue Line. That was definitely when I became aware of your films. I was living in Seattle at the time and I have seen everything since, retroactively going back and watching Vernon, Florida and Gates of Heaven. Though I still haven’t seen The Dark Wind. The shoe is its own thing. It’s a good story.

Morris: It’s a good story.

Marlow: It would mean nothing if you did not make great films.

Morris: Thank you very much. Somebody asked me this morning, ‘Could you imagine anybody who could replace Tom Luddy? Anyone else who could program this festival?’ I said, ‘The issue isn’t programming this festival. You could find lots of people to program this festival.’ Tom is extraordinary in a different way. He does a great job programming; it’s not a criticism. But Tom has created a community of people. I supposed I could do a pie graph of people I know through Tom Luddy and people that I know in some other way….

Marlow: Connected through Tom, yes. I have many of those as well.

Morris: I can tell you that most of the people I know, I know through Tom. Many, many people. He’s created a world of writers, reviewers, filmmakers and on and on and on. The legendary Rolodex (which is in his head). I used to tell people, ‘He was the only person I know who knew both the Pope’s telephone number and [Mikhail] Gorbachev’s home phone number.’ And I think it’s true.

Marlow: I think you’re right.