[Editor’s note: Keyframe begins a three-part series on Academy Awards past, beginning today with a ‘What If’ Oscars for the silent film years that pre-date the inception of the annual awards ceremony. It continues later this week by rectifying mid-century snubs, highlighting films that, in retrospect, richly deserved awards, and ends with a list of non-winning nominees from our past few decades who really deserved a trophy of their own. For a look at all the ‘alt’ awardees, peruse our e-book]

The Academy Awards were born in 1927, the brainchild of MGM’s Louis B. Mayer, a studio head whose original idea for an organization to negotiate labor disputes and industry conflicts evolved into the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. The awards themselves were an afterthought and initially more public relations gimmick than egalitarian celebration of the arts. Every member of the Academy (then as now an exclusive organization where membership is by invitation only) was involved in nominations but a committee of five judges picked the winners and Mayer, of course, oversaw it all. If he didn’t actually handpick the winners, be surely put his thumb on the scales. By 1929, Academy members were voting on the final ballots themselves and in 1934 the ceremony moved from November to March. Additional categories were added and other refinements made over the years (Foreign Language Film got its own statue in 1957) but otherwise the Academy Awards as we know them today were born: a glitzy event that brought the stars out and handed out trophies.

That leaves practically the entire silent movie era out of Oscar history. Hollywood had reached a zenith in terms of craftsmanship, glamor and ambition when The Jazz Singer was released before the first awards were handed out. It was. By its second year, sound films dominated the awards.

Let’s imagine an alternate history where the Academy Awards had been born earlier and (as long as we’re dreaming) with a more egalitarian purpose from the outset. What kind of winners might you have in an era when movies were more international and there was no such thing as a “foreign language film” when credits and intertitles were easily replaced for each region? What landmarks leading up to that first ceremony, where the twin peaks of populist blockbuster and artistic triumph—Wings and Sunrise—represented the Best of Hollywood, might have been chosen in the golden age of twenties cinema, or the birth of the feature film in the teens, or even the wild days of experimentation and rapid evolution in the decades previous?

Here are my picks for a few key awards in the imaginary Oscar history.

1928: Metropolis

Best Picture, Cinematography, Production Design

Released in January of 1927 in Germany and two months later in the U.S., this landmark was just too early for consideration in the inaugural awards (handed out in May, 1929). So I’m giving this early 1927 release a clear playing field with its own Oscar year: Academy Awards Year Zero. Sure, science fiction isn’t a big player with the Academy, but otherwise it has all the hallmarks of an Oscar favorite: epic canvas, astounding sets, visionary visual design and the timely theme of man struggling to find his place in the rapid spread of technology and machinery, all under the firm control of filmmaker Fritz Lang. Hollywood had never seen anything like it before. The film was soon edited down for and the original cut was lost for decades. The 2010 restoration restores scenes, characters and story lines unseen since opening night and confirms just how grand Lang’s vision was.

1926: The Lost World

Best Visual Effects

Special effects had been a part of the movies going back to the 19th century, when Georges Méliès brought stage magic to filmmaking, but that has nothing on what Willis O’Brien brought to life with clay, armatures and stop-motion effects in the original Jurassic adventure. The ostensible stars of the picture (Wallace Beery, Bessie Love and Lewis Stone), explorers in search of a fabled land where prehistoric creatures have survived and thrived, are all upstaged by Willis O’Brien’s dinosaurs. Though hardly realistic to modern eyes, these pioneering special effects are still a sight to behold, especially the lumbering brontosaurus that receives the most care from O’Brien, both foraging in his jungle and rampaging through the streets of London. The effects were so startling that these imagined Oscars created a new category to celebrate the achievements in the granddaddy of all giant monster thrillers.

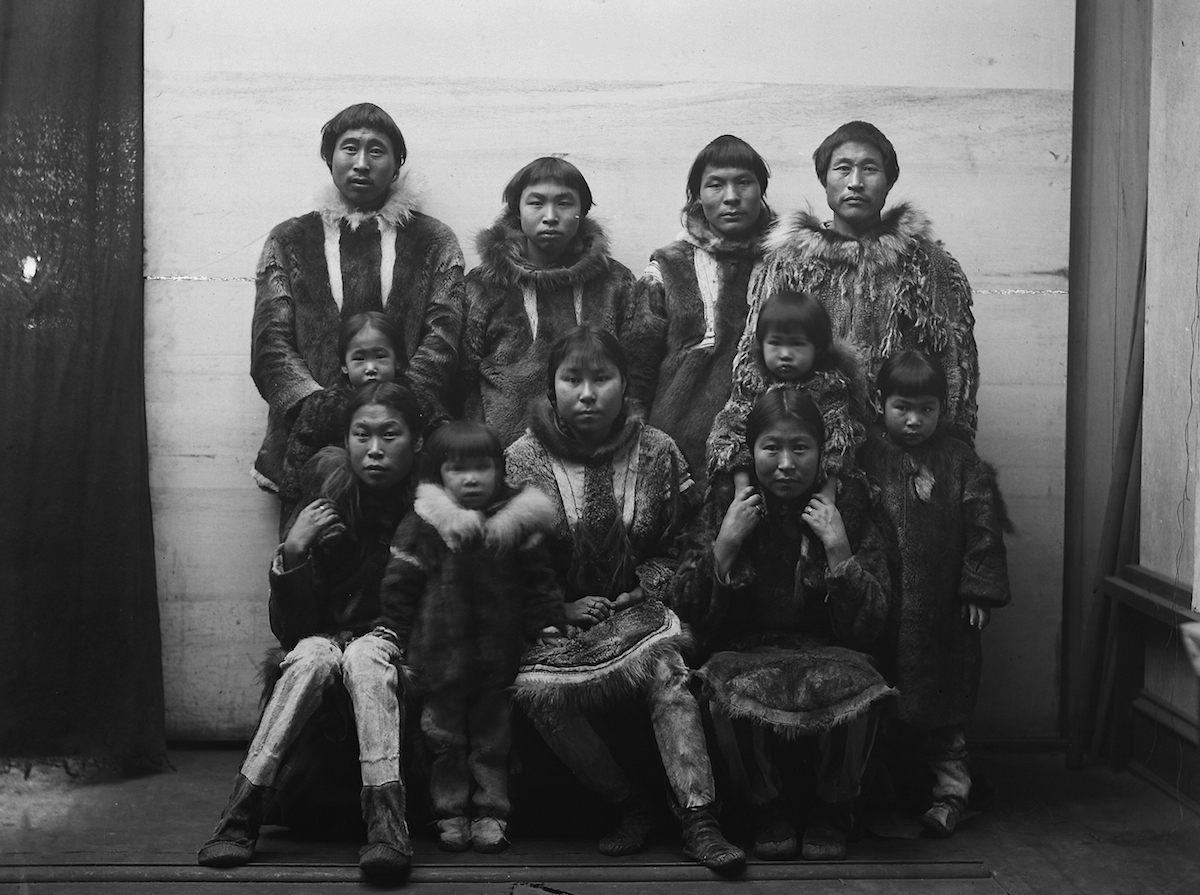

1923: Nanook of the North

Best Documentary

Admittedly, a documentary category might have been a little premature in 1922, but for the godfather of modern documentary filmmaking I’m making an exception. Robert Flaherty‘s portrait of traditional life among the Inuit people of the Arctic Circle wasn’t the first documentary by far—the actualities of the Lumières were nothing if not documentary recordings of their world and everything from major world events to glimpses of exotic places were filmed for interested filmgoers—or even the first feature-length non-fiction film. It was, however, the most influential. Flaherty discovered that the culture he wanted to show no longer existed so he recreated scenes of fishing, hunting, building an igloo and domestic life for the camera with the Inuit “subjects.” Which also makes it the first great documentary controversy. Flaherty and his actors deliver a drama of survival in a severe and unforgiving environment, and though it may seem naïve by modern standards it remains moving, involving and quite beautiful.

1920: Broken Blossoms and True Heart Susie

Best Actress Lillian Gish

Yes, back in the day performers could get two roles listed for a single nomination. It’s a little unfair but Ms. Lillian Gish, the first lady of American screen acting, certainly earns the honor. Working with director D.W. Griffith, she brought a subtlety and sophistication to screen acting, investing Griffith’s portraits of pure-hearted maidens with a glow of benevolence along with pluck and perseverance and fortitude. In Broken Blossoms, Griffith’s most tender film, she’s the forlorn daughter of an alcoholic brute who finds tenderness from a dreamy Chinese immigrant in London (played by American Richard Barthelmess), and in Griffith’s True Heart Susie she’s the epitome of the sweet, dreamy, naïve country girl as an eternal child oblivious to the social realities around her. Gish could do histrionics with the best of them, of course, wringing emotion from a passionate plea or an emotional outpouring, but was brilliant when stripping away artifice to create intimate shifts in a nearly still performance.

1919: The Outlaw and His Wife

Best Picture

The upset of 1919 Oscars as I’ve conjured them was this Swedish import taking the crown from superstar Charlie Chaplin, storytelling giant D.W. Griffith and favorite son Douglas Fairbanks (whose films with director Allan Dwan delivered American can-do spirit at its most energizing). But nothing Hollywood produced came close to the storytelling sophistication and dramatic intensity of Victor Sjöström‘s masterpiece. Set in 19th-century Iceland and shot against the dramatic landscape of Mount Nuolja in Northern Sweden, Sjöström creates images both beautiful and elemental to match the burning passion between rugged farmhand Kari (played by Sjöström himself) and the generous and compassionate widow Halla (Edith Erastoff). But for all its beauty, the primordial majesty and spiritual purity of the natural world is as unforgiving as the society that would deny their love and marriage “in the eyes of God.” Sjöström set a new bar for Hollywood filmmakers.

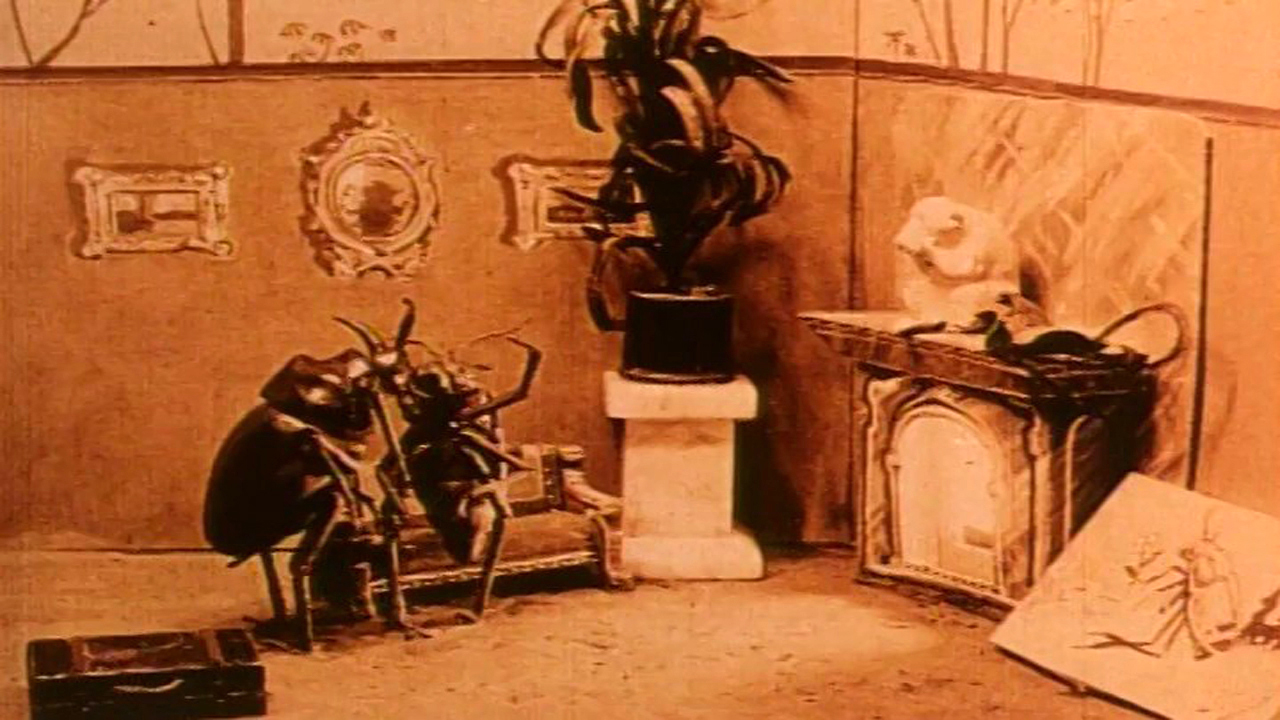

1912: The Cameraman’s Revenge

Best Animated Short

Animated cinema, pioneered by Émile Cohl in France and Winsor McCay in the U.S., was still something of a specialty when filmmaker Ladislas Starevich turned to stop motion techniques to create the first puppet-animated films. Who would have guessed that a director of natural history films could so adeptly transform the subjects of his early work (beetles, grasshoppers and other insects) into players in a satirical comedy of infidelity, jealousy and vengeance? It’s a wicked farce with a decidedly adult sensibility, early Cecil B. DeMille meets Mack Sennett yet made before either of those artists had established their careers, and created entirely with actual (dead) insects brought to life one frame at a time. Admittedly there wasn’t much competition in the animation category in 1912, but such a convergence of innovation, imagination and sophistication deserves some kind of recognition.

1902: A Trip to the Moon

Best Picture

Georges Méliès’ landmark fantasy short, “the first international hit in motion picture history” (in the words of film historian Serge Bromberg), imagined space flight before the Wright Brothers took their first powered flight. Though ostensibly inspired by Jules Verne’s book, Méliès was a magician and showman before he was a filmmaker and he made the cinema’s first portrait of space travel a pure flight of fancy, complete with showgirls cheering on the first astronauts and insectoid moon monsters exploding into clouds of stage smoke. Constructed out of magnificent hand-painted stage flats and then-revolutionary special effects (a mix of technological discovery and stage magic tricks), it was the first special effects-driven spectacle of the movies. It’s also a delight, a work of pure, playful imagination with a whimsical portrait of science as wizardry by way of the industrial revolution. The restoration of the pulsating hand-painted colors of the day only enhances its creative energy.

1895/1927: Dickson Experimental Sound Film

Special Academy Award to William K.L. Dickson for Technical Achievement

And we end up back at the birth of the sound revolution. Long before the nickelodeons created a moviegoing audience, Edison Company engineer William K.L. Dickson married the early motion picture technology he had developed with Edison’s phonograph and recorded a scene with both devices simultaneously. It isn’t even a minute long. It never played for the public. And its entertainment value is negligible—it was a test, not a piece of theater—yet it imagined the possibilities of the technology three decades before its commercial potential began to be realized. Even I can’t come up with any fantastical explanation for the Academy Awards existing back in this primordial era of early cinema but what would be more fitting for the first ever Academy Awards to honor the man who developed Edison’s movie camera and created the first synchronized sound film?