[Editor’s note: Keyframe begins a three-part series on Academy Awards past, which began earlier this week with a ‘What If’ Oscars for the silent film years that pre-date the inception of the annual awards ceremony. It continues here rectifying mid-century snubs, highlighting films that, in retrospect, richly deserved awards, and ends in the coming days with a list of non-winning nominees from our past few decades who really deserved a trophy of their own. For a look at all the ‘alt’ awardees, peruse our e-book]

What is excellence but the mastery of form and who better to judge than those with the most experience? So goes the thinking of any academy, based on the medieval guild structure (think Académie française whose immortelles hold office for life and decided le logiciel over le software). But mavericks have their value and nothing gets a bigger groan from the television audiences on Oscar night than Dr. Dolittle getting a nomination the year of The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde. Even though we know the odds are long and the game is rigged (6,000 insiders won’t ever please all the critics all the time), we indulge in wishful thinking, imagining a world that rights the wrongs of our “immortals:” Grace Kelly’s win over Dorothy Dandridge, one win only for Henry Fonda; My Fair Lady over Dr. Strangelove; 1958’s Touch of Evil never even invited to the party. Not to mention the schizophrenic 1970s, when the Academy vacillated between the ridiculous (Cinematography Award to The Towering Inferno over Chinatown, Sylvester Stallone for Rocky over Lina Wertmüller for Seven Beauties) and the sublime (Days of Heaven), particularly in the foreign-language category, a miraculous repository of some enduring (Italian) classics (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis to name one). So, from Hollywood’s Golden Age through the hidden talents of the Black List to the nadir years of overblown studio epics and the inevitable aesthetic wars between the studio behemoths on their way out and the nibble indies about to storm the box office, here’s a fanciful look at cinema’s middle years.

1931: Salt for Svanetia

Best Cinematography (Silent)

In Hollywood’s rush to sound, the Academy also wasted no time bestowing a special prize at its first ceremony on The Jazz Singer for “revolutionizing the industry.” By the second year, Outstanding Production went to Broadway Melody. Meanwhile the world was still making silent films—good ones, too. Yasujirô Ozu’s I Was Born, But… (1932); The Goddess (1934), starring China’s biggest star, Ruan Lingyu; and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr, which is basically a silent with added sound. In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Kalatozov, later celebrated for The Cranes Are Flying, Letter Unsent and I Am Cuba—all made with the same breathtakingly fluid camera moves he first picked up in the silent-era—directed this ethnographic film shot on location in a remote, salt-deprived Caucasus mountain range in his home province of Georgia. The American government didn’t formally recognized the U.S.S.R until 1933 and the Academy didn’t have a documentary category until the propaganda films in World War II, but it’s not without precedent for Salt to have picked up a win: the Academy gave its third cinematography award to With Byrd at the South Pole. Those were the days.

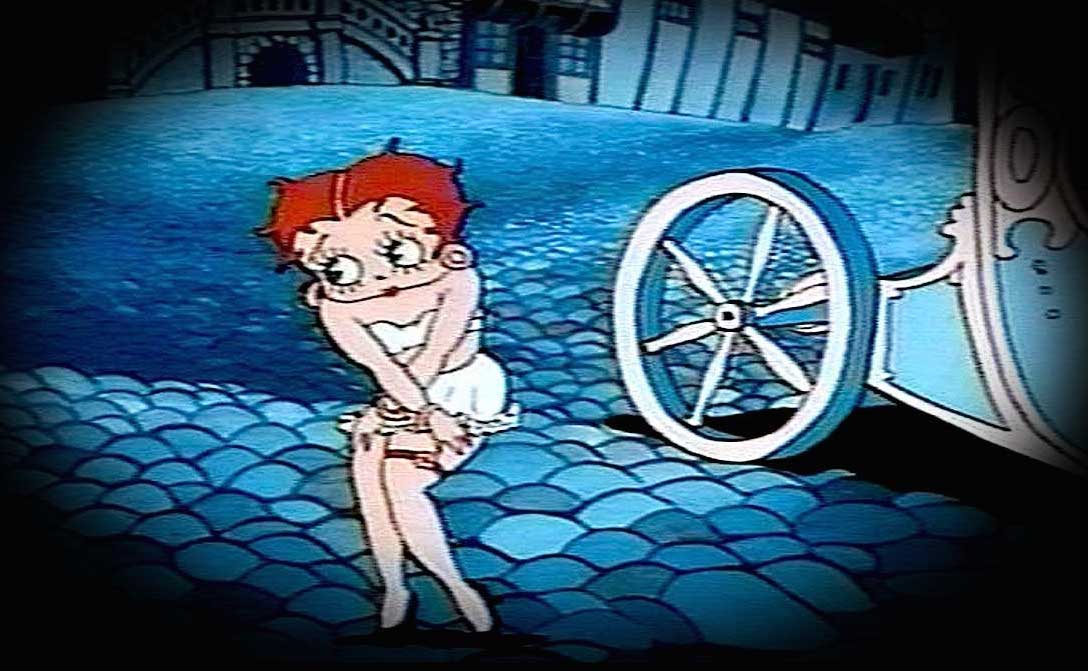

1935: Poor Cinderella

Short Subject (Cartoon)

The Fleischers deserved an Oscar long before the 1941 win for Superman. This cinematic marvel, with its astonishing depth of field, rivals anything the Oscar-monopolizing Disney put out. For the film, the Fleischers deployed their patent-pending device, the Setback, a turntable platform that allowed for the simultaneous photographing of layers of miniature sets and hand-drawn cels to create a three-dimensional universe that moves. Shot in Cinecolor, because Disney had an exclusive four-year contract with Technicolor to animate in its full-color process, Cinderella displays all the best of the endlessly inventive Fleischers: the gags (one hopeful’s big toe wagging its verdict on whether the glass slipper fits); sound effects (clomping coach horses provide the backbeat for the title song); a red-headed Boop (with some remaining va-va-voom before the Production Code inhibited her) against azure-mountains majesty. A shot lasting only seconds, high-wigged royals arriving in dark silhouette against the baroquely colorful ballroom, proves Cinderella is not only a groundbreaking cartoon, it’s cinema.

1941: June Night

Best Ensemble of Extras

There’s a campaign afoot to add an Oscar category in casting. Casting directors—so the argument goes in 2012’s Casting By, which gives hilarious short shrift to the opposing side represented by Taylor Hackford. (Is it possible the doc maker didn’t know he’s married to Helen Mirren?) Actors are the largest contingent of Academy membership and have always been except for a brief period in the early 1930s because of a dispute with the guilds. Paying tribute to those who get them their jobs makes sense. A Casting Director branch was added in 2013, so it might not be too long now. I tend to agree with poor misrepresented Hackford that the film’s director retains control over casting choices, at least for the principals. So I propose a compromise: an award for Outstanding Achievement in Making the Background Believable. This film by the accomplished Swedish film director Per Lindberg perfectly illustrates the crucial role of an ensemble of extras. Ingrid Bergman in the lead was a no-brainer, but those townsfolk in the courtroom scenes? They (and whoever cast them) deserve an Oscar. Casting directors can accept the statuette as long as they name all the extras in their acceptance speech.

1946: Scarlet Street

A Sweep

Brought over from Berlin because of his blockbuster spectacles, Fritz Lang’s relatively low-key American career must have been an enormous disappointment to Hollywood. He remains one of the all-time greats, despite his Academy shut-out, which is unforgivable, especially in light of this burnished masterpiece that turns noir-conventions inside out before the genre had a French name. Its virtues are legion: nighttime city streets slick with rain, a richly thickened plot, unremittingly venal characters and a Hays’s office-sanctioned ending that defied the proscriptions of its own Production Code. Oscars are due not only Lang but to screenwriter Dudley Nichols and photographer Milton R. Krasner, as well as to the unfairly overlooked Dan Duryea, at the top of his slippery, wise-acre game. While we’re at it, give Best Picture to producer Walter Wanger for staying in business with the director and to Wanger’s wife and business partner, Joan Bennett, who blossomed as a brunette under Lang. Watch her string along, while she gets strung along, over a rum Collins with horny henpecked Edward G. Robinson. Extra kudos to Lang for his dual digs at art world elitism and the uncultured masses.

1954: Thérèse Raquin

Best Foreign Language Film

Marriage is murder in this adaptation of Émile Zola’s tragic novel of an adulteress, which Marcel Carné deftly turned into a humanistic noir. The lovely Simone Signoret is yoked to a cold-fish mama’s boy, so when love storms through the storefront of the family business, we’re happy for her. But soon, someone is dead, and someone must pay. We’re kept guessing as to how destiny will collect its debts, but an unsettling dread builds with every scene as we’re convinced that no one deserves their fate. When a crowd of onlookers gathers outside the store window to watch the tragedy unfolding within (in a stunning deep-focus shot), the whole world knows how it must end. The Academy didn’t establish a foreign-language category until after the war, even as some titles occasionally showed up in other categories (Á nous la liberté and Grand Illusion) and for some reason did not name any foreign language film in 1953. Signoret eventually garnered a statuette for her English-language work as a “woman of a certain age” in 1959’s Room at the Top.

1955: Silver Lode

Best Art Direction

Honorary Achievement Award to Director Allan Dwan

Shot in tight spaces with deep focus and a muted Technicolor palette by noir cinematographer John Alton, this western about a shady authority figure trying to arrest someone on a dubious charge might be the best of Allan Dwan’s late films. Released the same year that Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront swept the Oscars, its relative obscurity is even more poignant. Though Dwan consistently denied the correlation, the story is an unmistakable allegory for HUAC’s Hollywood witch hunt. It was also released the same year as Rear Window, Hitchcock’s nominated morality play about the costs (and benefits) of peering into other people’s lives. Dwan weaves in a subtler motif, with the hunted and the hunters keeping tabs on each through the town’s windowpanes and drawn curtains. Townsfolk meanwhile resemble a fickle Greek chorus, their opinions changing faster than a gunfighter can draw. Art director Van Nest Polglase, who used Fourth of July bunting to critique American indifference, deserves the win. Dwan praised Polglase, better known for drinking than for his six previous Oscar nods, as “a great guy to take one set and transform it into another one with very little money.” Surely a virtue in Hollywood. The Academy could also have used the opportunity to acknowledge Dwan’s unsung fifty-plus-year career.

1963: Visit to a Foreign Country

Best Short-form Documentary

Lighter cameras, faster film (for shooting in low light), and the portable Nagra gave filmmakers the mobility to capture images and sound as it unfolds, making the audience feel part of the action. Michel Brault and Gilles Groulx had made an impression among documentary filmmakers with 1958’s Les raquetteurs. After seeing the fifteen-minute film, which gets right up in among the snowshoers at a convention in Quebec, Jean Rouch pressed Brault into service on his groundbreaking cinema verité project, Chronicle of a Summer. Back home, Brault shot (with Claude Jutra) this charming little gem about American tourists who flood Montreal’s summer in search of a closer, cheaper Paris. Joining an African American couple in their Cadillac, the filmmakers weave and whoosh with them around town, capturing poetic imagery of the city they clearly love. Documentary filmmaking had changed forever, but the Academy seemed not to have noticed, blind to pioneering filmmakers like the Maysles brothers (Salesman, Primary) until their first Christo film a decade later, and, most egregiously, ignoring William Greaves and his exuberant genre-defiant Symbiopsychotaxiplasm.

1969: The Red and the White

Achievement in Black-and-White Cinematography or, at least, a Foreign Language Nod

As Americans developed a warier view of war, some filmmakers picked up the zeitgeist. The Academy gave Peter Watkins the win in 1966 for his effective docudrama, The War Game, an it-can-happen-here of nuclear holocaust. Still, two years after the Tet Offensive, Patton kicked M*A*S*H’s ass. In the year that it honored the deserving Closely Watched Trains, the Czechoslovakian film that used WWII has an allegory for Soviet oppression, the Academy could just as easily have chosen this critics circle favorite, which uses the Russian Civil War as an allegory for the non-heroic nature of all war. Miklós Jancsó’s camera seems in constant movement as it follows a series of hapless protagonists, Communists and Cossacks both, whom we never are allowed to get to know. Capricious and chaotic, warfare turns villains into victims in an instant. The camera speeds quickly away or stays remote from all deaths, rendering each one meaningless. It’s no surprise that the Soviets tinkered with the film’s ending then finally banned it, or that middle America couldn’t yet handle its antiwar message. But a wiser Academy could have at least extended the black-and-white award categories a few more years to acknowledge its galloping cinematography.

1973: Cousin Jules

Best Documentary (Feature)

Dominique Benicheti’s soundtrack for this gorgeous, textural cinemascope documentary consists of only ambient sound (recorded in stereo!), allowing you to peacefully relish the wide-angle view provided by La nuit américaine cinematographer Pierre-William Glenn. Set in bucolic Burgundy among its naturally impressionistic hues, the film respectfully records the steady rhythms of the daily routine of a blacksmith and his wife: gathering wood to make the fire to heat the steel and getting water from the well, the first step in the long worthwhile process of sharing a cup of freshly ground midday coffee. “I made a sketch of each scene,” said the director, then in his early thirties, about Cousin Jules, which tests the limits of the documentary—discarding reporting, fact recitation and interviews all together—as well as strains the confines of the story film. There is no inciting incident, no denouement. Benicheti’s legacy is evident in subsequent observational documentaries, especially the camera virtuosity and canny framing of Leviathan, People’s Park, Manakamana, produced by the ten-year-old Sensory Ethnography Lab housed at Harvard, where, 30 years ago at the invitation of Robert Gardner, Benicheti rigged up widescreen and 3-D equipment and planned future films.

1979: A Walk Through H

Best Short Film (Live-action)

Exhaustive raconteur of the vividly unusual, Peter Greenaway made this mesmerizing BFI-financed film two years before his plus-sized The Falls launched his feature career. Ninety-two canvases painted by the director serve as maps for a 1,418 mile journey through a placed called H, which is forever delineated but never defined. The camera pans around the intricacies of each dark opaque oil as a first-person narrator describes receiving cryptic directions and dubious advice, getting lost, tracking back, occasionally sharing fascinating anecdotes of birds. In the end, we’re back in the gallery where the film’s initial tracking shot ensnared us in this mesmerizing world in the first place. Greenaway made it, he said, as a way to know his deceased father, who hoarded decades of bird facts in five suitcases that inspired the director’s alter ego, Tulse Luper. The Academy tends to ignore the experimental except as it seeps into movies it understands (some Buñuel, American Beauty, etc.). Watching this whimsical, melancholy film, you can almost hear the idiosyncratic voiceovers and feel Greenaway’s touch in the painstaking, hand-made sets and slowly moving, wide-angle camera of Wes Anderson.