In Los Angeles, the trial of Lonnie Franklin, Jr.—the alleged “Grim Sleeper” serial killer—is finally about to start. It’s been five years since DNA evidence led to Franklin’s arrest for ten counts of murder and one count of attempted murder (he pled not guilty), but the killings in South Central L.A. began in 1985, maybe earlier. The victims: women of color, many of them prostitutes, many of them caught up in the crack epidemic that was sweeping through the city at the time. To the outrage of their family and friends, their deaths were not considered a high priority by the LAPD, and it’s taken decades for the wheels of justice to creak into motion.

Into this complex tale wades British documentarian Nick Broomfield (Kurt and Courtney, Biggie and Tupac, Aileen: The Life and Death of a Serial Killer), whose investigative style involves making himself a prominent part of the story, using just a camera person (he does his own sound recording) while tracking down witnesses, clues and leads the police might have missed. Though South Central is an insular place, Broomfield was able to find sources that helped him piece together the tragic, frustratingly under-the-radar saga of the Grim Sleeper (so named for a gap in the killings between 1988 and 2002) and his victims. The resulting film, Tales of the Grim Sleeper, may be his most powerful work to date.

Cheryl Eddy: You could have called your film The Hunt for the Grim Sleeper, or something along those lines, but Tales of the Grim Sleeper is so much more evocative. It speaks to the ways in which storytelling has shaped the case, and subsequently this documentary.

Nick Broomfield: I felt it was really a film about stories surrounding him. After awhile, I think his guilt isn’t the salient question. It’s not a whodunnit: Did he do it? Did he not do it? It’s more, how is it possible that he did it? How is it possible that for twenty-five years in the center of Los Angeles, this guy managed to kill probably way over 100 women? How did nobody know? Why didn’t the police do anything? What does it say about that community, what does it say about the LAPD? It raises all those questions.

And then, when you’re talking to [Lonnie Franklin, Jr.]’s friends, it’s ‘Didn’t you know something was going on?’ You come across all these women who narrowly avoided being killed by him, who ran naked down the street, or had their throats slit by him. It’s like, ‘Why didn’t you talk to the police?’ So it really becomes the tales of this web of confusion, a breakdown in relationships between the people who are meant to be protecting and serving this community, and the people in the community who are terrified and distrustful of the police. The local politicians who don’t really feel it’s their job to serve the community. And a community that’s been abandoned, where house prices are so low they can’t really move out, and nobody wants to move in. It’s this very stagnant population.

It’s all those kinds of things, and a community that has a big crack problem that came from the early 1980s. There’s been no comprehensive attempt to deal with the epidemic. It’s been treated as an individual problem. So it’s still there, and that pervades a lot of the film. It’s part of the weird coloring of what goes on there. And it enabled the [Grim Sleeper] situation to happen.

Eddy: When you first started making the film, did you realize the case would have so many complex layers, or did you expect it to be a more straightforward crime story?

Broomfield: As somebody who’s spent a lot of time in Los Angeles, I was aware that there are two very distinctly different cities. The city that I’m a part of, which is the very white, Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, city. And then there’s this other city which is poor, black, Hispanic, very very different. There’s very little exchange between the two. The buses aren’t used by the white population. It reminds me, incredibly, of Johannesburg in its worst apartheid moments, where I filmed before Mandela came out of prison.

I was curious, really, when I read the story of [Franklin’s] arrest, and subsequently there were some great articles in the LA Weekly and a great one in Newsweek. I thought, ‘Well, I’ve always been interested in this part of the city, and this was a great opportunity to do [something about] it.’ So that was more my starting point. But also the starting point of, how was it possible for this to happen for twenty-five years? This would not have happened in Santa Monica or Beverly Hills. After the second murder, they would have locked the whole place down. They would have done house-to-house searches, they would have been stopping cars, they would have ripped the whole place apart.

But here, you’ve got a situation where probably hundreds of women have disappeared. We’re not just talking about 100. I think in 1987, they had a count of ninety-seven missing women, and these murders went on until 2010. You’re talking about a lot of women. In [Franklin’s] house, they found pictures of 180 missing women, that he’d taken. That would never have happened anywhere else in the city. No one really in the surrounding streets even knew about all these women disappearing, because it wasn’t reported in the LA Times. It wasn’t reported on the local radio. People just didn’t know.

The police had known from 1987 that there was a serial killer who had murdered at least eight women. They had the gun, they had the ballistics, but they didn’t release this information for another twenty-two years. When I asked them why, and unfortunately I wasn’t filming it, they said, ‘Oh, we didn’t want to tip him off. We didn’t want to let him know that we were on to him.’ Crazy stuff, you know.

Eddy: The Grim Sleeper’s neighborhood, South Central, is practically a character in the film. As you mentioned, you’re from the ‘other’ Los Angeles. Did you have a hard time finding an entrée into the community? There’s a scene in which some of Franklin’s friends are shown taunting you from across the street, calling you ‘peckerwood,’ which goes pretty quickly into them being surprisingly open interview subjects.

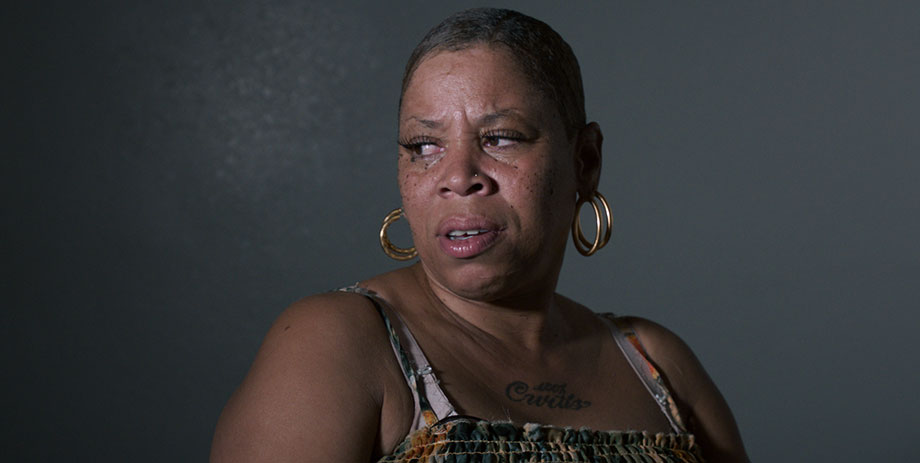

Broomfield: That was almost the hardest thing, and I’ve learned while working on these kind of films that you want to have the right person to go into the community with. When we started, we hadn’t yet met Pam [the film’s charismatic South Central ‘tour guide,’ who knew Franklin personally]. I interviewed people for a couple of months, then we met someone named Tiffany Haddish, who later had a regular part on the Kevin Hart show Real Husbands of Hollywood [and is now on Tyler Perry’s If Loving You Is Wrong]. At that time she was a local comedian who’d grown up on the street next to Franklins. She’d had an incredibly tough upbringing, but had managed to use her upbringing for humor in comedy workshops and comedy clubs. She was very well-known, a kind of success story in the neighborhood. So she came with us the first day and was able to sort of diffuse the whole ‘peckerwood’ incident, [because those guys] knew who Tiffany was. She was just the right person to go into the community with. But she suddenly started becoming quite successful, and Pam really took over.

Eddy: How did you meet Pam?

Broomfield: We actually met pretty much the first day. She was one of the women who did an interview with us, because she’d been with Lonnie and we were introduced to her as someone who’d been hooking and had been on crack. And then we met her a couple more times. We had this really dumpy office near [South Central], and Pam would come over there and play cards. A lot of the people from the neighborhood would sort of pop over and see us, because they didn’t really like talking to us in the street. They didn’t want us in their houses. So they’d come to our office and it became a bit of a social place.

And then when we were going out filming, it just sort of organically developed that Pam would come with us. Obviously she knew so many people, and it all just sort of fell into place. You know, what I like about making these films is that you make them in an organic way. You allow the films to develop in a natural way, and avail yourself of local talent like Pam, and establish relationships as you go along. That way, you potentially can make much more interesting films than if you go in with a scenario and a written script. I think more and more documentaries are made by people who write scripts, which I think really defeats the magic and the power of making documentaries. The spontaneity is lost.

Eddy: Was it completely impossible to talk to Lonnie Franklin, Jr.?

Broomfield: We had the backing of his defense attorneys to talk to him. They signed the application that we made to the sheriff’s department. They wanted us to talk to Lonnie. But I think because the story is so politically sensitive, the sheriff’s department were the ones who refused to let us go in. There’s a very tricky DA working on the case who I think is her own worst enemy. It’s so funny when you make these films, I always imagine we’d get on rather well with the DA. But I actually found the defense a lot more approachable. They were eccentric, but clever.

Eddy: Do you think you’ll film the trial, or do a follow-up to Tales once it’s over?

Broomfield: I really don’t know. I’m fascinated by the story, and I was speaking to a couple of the defense attorneys the last couple of the days, and they were quite keen on my doing a bit more. But I don’t know. I think I would need to feel that it was going to reveal something that we didn’t know, that wasn’t already in this film. I don’t know what that would be.

I think he’s very obviously guilty. There’s a lot of evidence that hasn’t been revealed yet, which I think will be horrendously dark. I don’t know that one necessarily wants to immerse oneself in that. I think maybe the level of where the film is at now is a much more interesting one.