Just four years younger than Cannes, 2013 marks the Melbourne International Film Festival’s sixty-second year. In 2012, the official festival image featured the hand of the undead triumphantly thrusting a spool of film into holy light from a sea of empty reels (in clear reference to the hand from the poster artwork for the original The Evil Dead, 1981). With film festivals worldwide having made the transition from film to digital projection (including Cannes), this image appeared like a harbinger for the format’s own ‘final scare’ before its inevitable death. Surprisingly, in the wake of the digital revolution, the program for MIFF 2013 included an impressive total count of twenty-three film prints (two 16mm and twenty-one 35mm). It would seem there are survivors yet on the post-apocalyptic, digital festival circuit landscape. Beyond the two experimental shorts and some new titles produced out of Europe and Asia, the festival combed the far ends of Italy to locate and screen six supremely rare Italian Giallo films from the 1960s, seventies and eighties, curating a curious mini focus on the genre, titled Shining Violence: Italian Giallo.

The word Giallo simply means ‘yellow’ in Italian, and the film genre takes its name from the bright yellow colored paperback covers from the 1920s, thirties and forties Mondadori produced pulp mystery fiction books. It is not surprising then that the first screening in this series should be Dario Argento’s Tenebrae (1982), a film whose protagonist, Peter Neal (Anthony Franciosa), authors precisely this kind of crime novel. A crazed fan turned murderer, whose kills all feature pages of the novel stuffed into the dead victims’ mouths, stalks Neal. Apparently inspired by Argento’s own experience of being stalked by a crazed fan, Tenebrae, brimming with beautiful blood spatter, close-ups on leather gloves and a sensational score by Goblin, is Giallo 101 for the uninitiated.

Shining Violence continued with another film from Argento, and one of the more popular examples from the genre, Profondo Rosso (Deep Red, 1975). David Hemmings stars as musician Marcus Daly, the man who happens upon a gruesome murder and then teams up with a beautiful no-nonsense reporter in this more traditionally noir-style mystery thriller. Constantly playing with gender roles and stereotypes, as well as childhood memories, this might be one of the more straightforward films from the genre, bathed as it is in psychoanalytic subtext.

Two very palatable films into the focus, Shining Violence continued with another Italian horror master, Lucio Fulci. Less bloodthirsty than his later films like Zombi (1979), City of the Living Dead (1980) and The Beyond (1981), Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972) is beautiful examination of how varying forms of authority can be misused to systematically exploit young children. Presenting ritualistic beliefs in stark contrast to the depiction of established institutions such as the family, the church and the law, Don’t Torture a Duckling takes a bold Althusserian approach to the types of physically and ideologically repressive state apparatuses most prevalent in Italy’s fascist past.

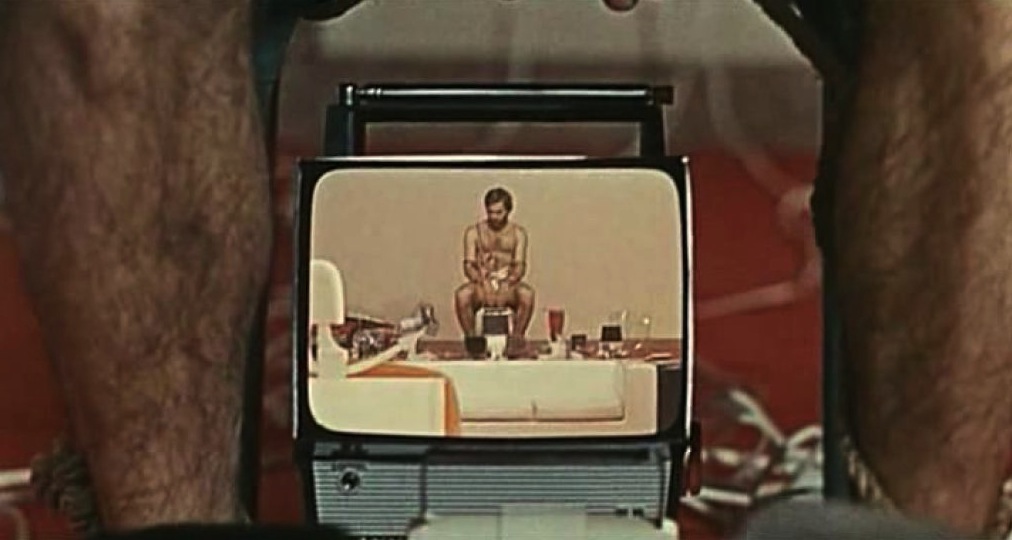

Fulci’s socially and politically charged film was followed up by Elio Petri’s equally stimulating and visually stunning, Un Tranquillo Posto Di Campagna (A Quiet Place in the Country, 1968). In a film where anything could be real or imagined, the ‘story’ centers around young artist Leonardo (Franco Nero), who suffers a severe anxiety attack before moving to a strange, dilapidated house in the country. Constantly in flux between sexual excitement and extreme anxiety, Leonardo begins a relationship with the apparition of a countess-turned-whore who once lived and deviated within its walls. Increasingly, as Leonardo descends into madness, the separation between fantasy and reality almost entirely blurred, so too does his relationship with lover/art dealer Flavia (Vanessa Redgrave) descend into darkness.

The most adventurous in the collection presented at MIFF, Petri’s film is an innovative and at times experimental exercise in questioning the extent to which the commodification of art exploits the artist. Slowly, the house and the people around him become his canvas, and Leonardo finds himself exploited by capitalism. The red color of communism comes and goes throughout the film just as the faded red from the blood of the past faintly persists. Culminating in the thrilling unearthing of past fascist military horrors, and conflating the regime with the systematic mental degradation of those who suffer under its exploitative conditions, Petri’s film is an astonishing multilayered achievement. Lingering along with the aesthetic impressions is Ennio Morricone’s deeply unsettling yet constantly playful score.

The final two films in the focus, less concerned with high dramatic stakes and more interested in tone and atmosphere, were La Ragazza dal Pigiama Giallo (The Pyjama Girl Case, 1977) and The House of the Laughing Windows (1976). Shot with Sydney harbor as its backdrop—with the Opera House almost constantly in view—Flavio Mogherini’s La Ragazza dal Pigiama Giallo is a slow-paced crosscut narrative. One thread of the film follows an inspector searching for a killer in a bizarre case where a young woman is found dead; shot, bludgeoned, then set on fire in an abandoned car on the beach. The second thread follows a young Dutch female immigrant and her simultaneous affairs with her Italian husband’s German best friend and a local sugar daddy. More focused on the issues of identity, social welfare and displacement for European immigrants in 1970s Australia—despite being dubbed in mostly American accents—La Ragazza dal Pigiama Giallo is a slow burn with a brilliant payoff. At the center of the mystery sits an Italian and a pair of yellow pyjamas. La Ragazza dal Pigiama Giallo is a peculiarity of the genre that further reveals the human identity crises so often at its heart.

The final film was The House of the Laughing Windows, perhaps the strangest and most beguiling of the six films screened. Visually and thematically cloaked in soft focus with another eerie setting for unearthed secrets, The House of the Laughing Windows comes from director Pupi Avati, who was an uncredited writer on Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). The story is of a young male painter, Stefano (Lino Capolicchio), sent to restore a local church fresco, unfinished after its previous painter mysteriously disappeared. As odd behavior begins, Stefano finds himself drawn to a house on the outskirts of town that silently mocks passersby with sad, laughing windows. A slow, contemplative mood piece climaxing with a twisted reveal, The House of the Laughing Windows is another provocative Giallo concerned with gender and desire, and the alienation of isolated landscapes.

More than just mystery, thoughtful and thematically stirring beyond simple pulp fiction, Giallo is better defined through extensive viewing than surmising words. So often interested in tone and style above narrative and story, Giallo is a genre made for the big screen. Each of the film prints was more beautiful than the last with only surface scratches and a little dirt occasionally entering the frame. Two of the films, Tenebrae and Don’t Torture a Duckling were manually “soft-titled” during the screenings (soft titling is the superimposition of subtitles only onto the screen via another digital projector, manually operated by a technician) and Profondo Rosso appeared with the international release title, The Hatchet Murders, and twenty-eight minutes of cut footage. Along with some of the graphic violence, this version was missing a lot of exposition, namely the conversation between Marcus and Carlo that takes place early on by the fountain. Also cutting the exposed mural down to a single image, this version of the film is a great indicator for contemporary audiences as to just how common and invasive international censorship was during the 1970s–about as common and abrasive as the dubbing.

Cuts, scratches and strange titles aside, the supreme rarity of these six Italian Giallo films was a wonderful and welcome addition to the sixty-second Melbourne International Film Festival. With every flicker of shining light that passed through moving celluloid and onto the big screen, an auditorium full of Australians learned a little about la dolce morte–“the sweet death.”