Whatever happened to the truly “subversive” film? In the nearly four decades since Amos Vogel (1921-2012) first published his extraordinary and influential book Film as a Subversive Art, the word has lost a great deal of its relevance to North American cinema culture. It’s not as though there are no longer powerful institutions or conventions to subvert, but sometimes it seems as if every last taboo has already been smashed by someone else, and that attempts to upend aesthetic expectations are generally met with a collective yawn—a yawn that spreads quickly in a consolidating media landscape. A while back, when a rumor spread that new corporate owners had gone as far as to ban “subversive” (as well as “meta”) from the pages of The Village Voice, it was widely believed, although the word hasn’t proven to be eradicated there in the six years since.

When we hear early in Caveh Zahedi‘s latest diary/documentary The Sheik And I, that he was commissioned to make a film for an art festival under the theme “Art as a Subversive Act,” we may think of this as an almost quaint notion for a festival. That is, until the nature of the festival really sinks in. Called the Sharjah Biennial, it’s a large-scale exhibition of works by international artists, most of them with ties to the Middle East. It’s held every other spring in one of the lesser-known of the United Arab Emirates located just North of Dubai and Abu Dhabi on the Arabian Peninsula. For its tenth edition in 2011, the Biennial, which has only recently begun incorporating contemporary art as a major component of the festival, expanded its moving image art component by commissioning films by Zahedi, Karim Aïnouz, Bahman Kiarostami (whose father, Abbas Kiarostami, had his film Shirin screen at the 2009 Sharjah Biennial), and others.

By reputation, Sharjah is perhaps the most conservative of the United Arab Emirates. Ruled by Sheikh Sultan bin Mohamed Al-Qasimi for the past 40 years, the emirate enforces a strict dress code and forbids alcohol and the mixing of unmarried men and women. It’s an unlikely site for a festival celebrating subversion—unless we consider the long history of repressive regimes turning to art to signal institutional broad-mindedness, a broad-mindedness that may not exist in other cultural and political spheres under the regime. We all know the archetype of the king who allowed his court jester to use performance to reveal unpleasant truths he would never abide hearing from his ministers or other subjects. Is it accidental that the world’s two oldest film festivals, in Venice and Moscow, were established under despots Mussolini and Stalin? Even an American festival like Sundance does quite a bit to mitigate the image of its home state, Utah, as an entirely conservative wasteland.

His best-known film, ‘I Am A Sex Addict,’ is a self-reflexive confessional in which Zahedi frankly and humorously exposes and re-enacts his prostitute fetish, which destroyed the love relationships of his 20s and early 30s.

Enter Caveh Zahedi, a filmmaker of Iranian heritage but “100 percent American” by birth and cultural affiliation, and whose previous films often seem like the last things that would be endorsed in an undemocratic state in the heart of the Islamic world. His best-known film, I Am A Sex Addict, is a self-reflexive confessional in which Zahedi frankly and humorously exposes and re-enacts his prostitute fetish, which destroyed the love relationships of his 20s and early 30s. In The Bathtub of the World is a no-holds-barred video diary of a year of his life as a struggling filmmaker, teacher and human being in San Francisco. In I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore, he tries to convince family members to take ecstasy pills with him while on a Christmas road trip, with hilarious and expectation-shattering results. Actually, virtually all of his films, starting with his co-directed feature debut, A Little Stiff, include at least one scene in which Zahedi takes ecstasy or a large dose of hallucinogenic mushrooms in order to capture himself in a moment of irrational revelation. In fact mushroom trips are the entire raison d’être for two of his short films, I Was Possessed by God and Tripping with Caveh.

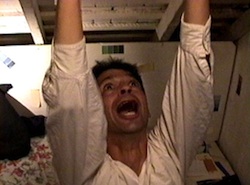

In I Was Possessed by God, Zahedi ingests a formidable quantity of mushrooms and lets the chemicals (or, perhaps, another spiritual entity, as the title suggests) take hold of his persona as his friend Thomas Logoreci records him with a video camera. The resulting 16 minutes that comprise the film’s final edit are a far cry from the mushroom trip videos one finds posted on YouTube—and not just because they predate them by a decade or so. Invariably, the latter show drugs ingested in party situations, or in natural settings, and the participants employ the camera simply as an instructional advertisement for their chemical choices, or as a weapon of humiliation.

Zahedi’s trip has elements of instruction and embarrassment, but achieves much more. Isolated in a confined attic space with only the cameraman, he uses his body and voice as pure performance instruments. But with the signal between rational thought and sensory activity scrambled, his wild gestures, elfin expressions and strange utterances are often as unrecognizably human as others are recognizably “Caveh.” How much, if any, of this performance was planned in advance? Is it possible to “act for the camera” while perception is so radically transformed? Or is it so radical a transformation after all? Is Zahedi struggling, as his body language sometimes indicates, or in the grip of pure pleasure? Why does he speak as lovingly of Jean-Luc Godard while high as while cold sober? Even those of us who have never experimented with psychedelics can be fascinated and entertained by the many questions I Was Possessed by God poses.

Tripping with Caveh is the first and only completed entry in an aborted attempt by Zahedi to create a low-budget television series allegedly modeled on John Lurie’s Fishing with John sextet. Where Lurie took the likes of Tom Waits and Dennis Hopper on international voyages to catch sea creatures, Zahedi brings singer-songwriter Will Oldham, a.k.a. Bonnie “Prince” Billy, to a Texas estate in order to share a psychedelic mushroom experience. Over a half-hour of screen time, the pair ride go-carts and bicycles, contend with the hazards of nature, and discuss subjects like the nature of fandom and love. Conflict comes between the perhaps intrinsically relaxed Oldham and the more high-strung Zahedi when the latter tries to convince his guest to increase his dose before his own higher dose begins to wear off. Zahedi calls this encouragement his “one directorial intervention,” and it reveals some of the contradictions in his process quite precisely. To return to the Fishing with John comparison, Lurie was in fact a novice fisherman who trusted that entertaining interactions with his celebrity partners would overcome lack of angling excitement for his viewers—and sometimes it didn’t (see the Matt Dillon episode). Zahedi is by contrast a seasoned tripper hoping to engineer a shared transcendental experience for the camera. Tripped up by his own expectations, it’s revealed near the end of the film that his anxiety about the shoot interfered with his own trip as well. The film’s exploration of varying registers of consciousness in art is completed with the lovely, seemingly impromptu private concert Oldham gives Zahedi, his wife Amanda Field, and the camera. Of course it becomes a participatory rendition of his song, “I Am A Cinematographer.”

‘Tripping with Caveh’s’ exploration of varying registers of consciousness in art is completed with the lovely, seemingly impromptu private concert Oldham gives Zahedi, his wife Amanda Field, and the camera. Of course it becomes a participatory rendition of his song, ‘I Am A Cinematographer.’

The Sheik and I documents the Zahedi’s relationship with the Sharjah Biennial from start to finish, with any important gaps in visual documentation filled in with simple animations reminiscent of those in I Am a Sex Addict. He traces how the festival curators approach him with promises of unlimited artistic freedom to make a film engaging themes such as treason, collaboration, and conspiracy. Perhaps intimidated by a completely blank canvas, Zahedi presses to uncover three restrictions on his project: no frontal nudity, no making fun of the Prophet Muhammad, and no making fun of the Sheik of Sharjah. He’s happy to comply with the first two requirements, but the third sparks his imagination. Who is the Sheik of Sharjah? What about him is there to make fun of?

A meeting between Zahedi and one of the curators in a New York restaurant seems an early ill omen. She seems surprised by the presence of his camera crew at the occasion, and her disposition only worsens when he proposes his ambition to involve the Sheik, whom he compares to the Wizard of Oz, in his film. She retains composure, likening him to a Rockefeller grantee investigating the oil magnate’s legacy; an empire built “on paradox and contradiction and injustice and what have you.” She warns her meal companion that “the system has a way of framing these attempts and blocking them.” Zahedi’s answer: “Sounds right.” Thus is set up the chess match between filmmaker and foundation that makes up the rest of The Sheik and I.

When Zahedi flies to Sharjah with his wife, their toddler Beckett, and a filming crew, he’s devising a trip not so fundamentally different from his mushroom experiments. In each case he knows what he’s getting into (making a film), and yet he doesn’t know. It’s the terrifying beauty of completely unscripted moviemaking. Not that Zahedi sees no utility in filming staged scenes. This style of filmmaking is something for him to document (he’s brought two cinematographers). As his tourist’s eyes begin to make observations about the unfamiliar city he’s in the middle of, ideas for a loose “plot” for his Biennial film to hang upon begin to flow. He comes up with an evolving narrative steeped in American preconceptions about the Arab world, in the spirit of the curators’ thematic suggestions of treason, collaboration, and conspiracy. He enacts his own anxieties about foreign travel as Hollywood action-thriller tropes, with a cast cobbled from whomever he can persuade to join his cohort, from family members to employees of the foundation and his hotel, to a chorus line of South Asian immigrant children who play in the local square.

Zahedi’s trip in ‘I Was Possessed by God’ has elements of instruction and embarrassment, but achieves much more. Isolated in a confined attic space with only the cameraman, he uses his body and voice as pure performance instruments. But with the signal between rational thought and sensory activity scrambled, his wild gestures, elfin expressions and strange utterances are often as unrecognizably human as others are recognizably ‘Caveh.’

By documenting how these enactments are brainstormed, revised, staged, frequently modified, re-staged, and commonly even nixed by their participants or the curators, Zahedi illustrates the ridiculous naïveté of his own project, as well as of the stereotypes he’s engaging with. And yet, many of these film-within-film moments have an almost iconic quality about them. One scene inspired by Sharjah’s lack of traffic signals shows a Biennial employee getting run over by a car, despite using the customary hand motion he’d promised Zahedi’s family would ensure pedestrian safety in the Emirate. It’s a fantasy sequence, but the result is cinematically convincing, and on the screen, the collision feels emblematic of all sorts of larger conflicts The Sheik and I brings up: religious vs. secular, ruler vs. subject, documentary vs. fiction, East vs. West, etc. That the corresponding roles of driver and pedestrian could be interchanged in each of these conflicts doubles the image’s symbolic impact.

The primary conflict of The Sheik and I, of course, is that of arts festival curator vs. incorrigible filmmaker. At various moments in the film, both parties take the role of the trusting jaywalker being run down by the other’s momentum. Despite apparent familiarity with his prior work, the curators seem blind-sided by Zahedi’s increasingly strong desire to involve political and religious themes in his film. Zahedi, in turn, is demoralized by his inability to involve the Sheik, or failing that a stand-in Sheik, in his filming, without possibly jeopardizing the safety of his cast. Release forms, requests for pocket money, candid comments about Sharjah’s divided society, and ultimately the specter of potential fatwa a la Salman Rushdie all complicate Zahedi’s freedom as an artist and/or journalist.

That the film continues to screen at all tells us something about how this all plays out in the end. But I don’t want to give away all of the film’s surprises, and in fact the chess match may not have reached its endgame. At the San Francisco International Film Festival this past April, Zahedi admitted that he continued to work on the film (though at press time, he had finished), and it may be that the question-and-answer sessions there were less contentious than those at the SXSW premiere because he’d added reassuring title cards to the end of the film. He also related that an influential programmer from a major North American film festival considers The Sheik and I unethical, and has been attempting to get the film pulled from those festivals that do program it, and contacting critics, urging them to ignore or negatively cover the film.

Which brings us back to the Biennial’s theme: “Art as A Subversive Act.” Perhaps it’s not such a quaint notion after all.