Federico Fellini loves his clowns. They are the stars of La Strada, part of the sideshow of 8 ½, and revelers in the dreamscape world of Juliet of the Spirits, and those are just the literal incarnations in whiteface and costumes. You find their cousins in Il Bidone and The White Sheik and the circus spirit in the society sideshows of La Dolce Vita and the flights of creative fantasy in 8 ½. He loved to cast clowns in his supporting casts and directed one of Italy’s great clowns in his movies: Polido (aka Ferdinand Guillaume), who played Pagliaccio in La Dolce Vita and appeared in Nights of Cabiria (as a monk), 8 ½, and Toby Dammit (Fellini’s section of Spirits of the Dead). The Clowns, directed for Italian TV (where it debuted on Christmas Eve, 1970) and subsequently released in theaters, is his celebration of these modern jesters.

It was Fellini’s second made-for-television production, a project he undertook after the liberating experience of making A Director’s Notebook a year earlier. After a decade of ambitious and creatively demanding productions—La Dolce Vita, 8 ½, Juliet of the Spirits, and Fellini Satyricon—these small films gave Fellini space to doodle and play in something small, to make something “without baggage,” as he explained in the book The Clowns, a companion piece published in conjunction with the film. “I saw the opportunity to make a new experience.”

Ostensibly a documentary, The Clowns is just as much a visual sketchbook, a pageant of the great clowns of Italy, France, and Britain, and a wake for the end of the circus clown era as it is a history of the art and culture of clowns. It opens with a wistful moment of wonder that straddles remembrance and dream: a young boy wakes in the night to find a circus tent being raised just outside his window. Dario di Palma is the cinematographer of record but Giuseppe Rotunno, who had just finished wrapping Fellini Satyricon, shot these scenes for Fellini in the early days of production. The atmosphere created by his dusky light is mysterious yet comforting, as if half awake, and it gives this prologue a quietly magical quality that stands out from the more familiar documentary style of the rest of the film.

From this remembrance we jump to the hard light of the adult world of practicality as the filmmaker Fellini (playing himself) rounds up a crew (playing themselves) to make his own film about the classic clown of the old-fashioned circus. Which makes The Clowns a film about a film about clowns. There’s a streak of La Dolce Vita and 8 ½, the self-aware media culture skewered both by Fellini’s brand of satire (a guest appearance by Anita Ekberg who plays to the camera like a starlet on the paparazzi walk) and by the madcap antics of the film’s clowns who refuse to take anything seriously. Fellini himself even gets in on the clowning around, so to speak, as he lampoons himself, the great director as a stooge in slapstick gags that erupt in the midst of interviews.

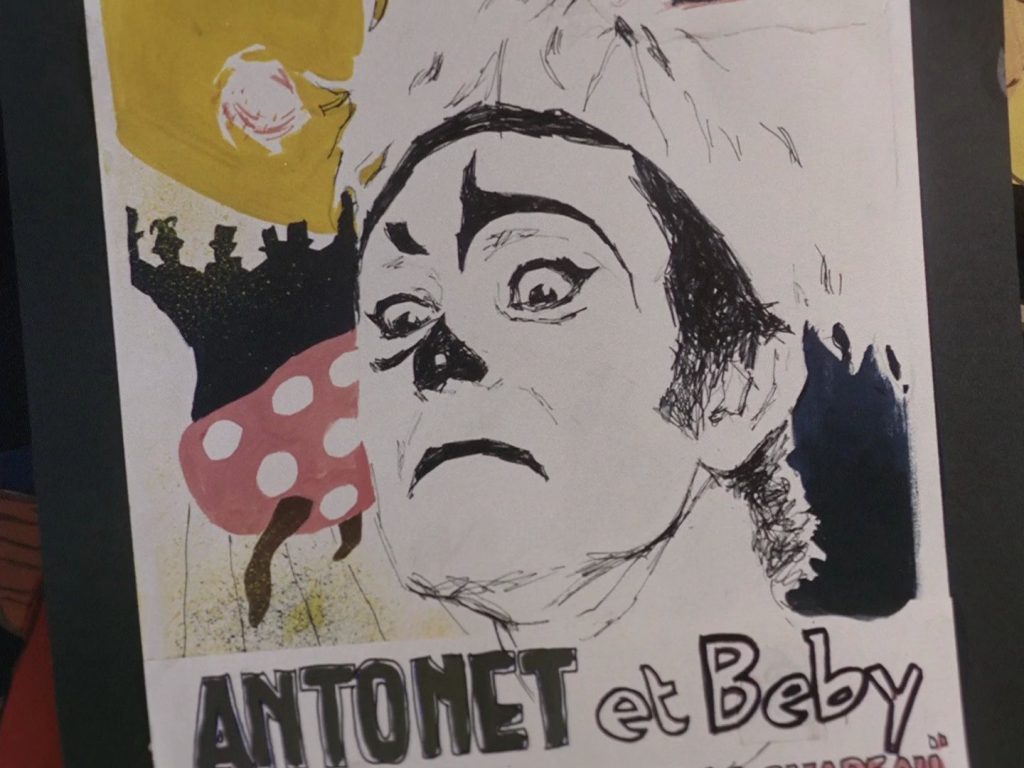

But digressions aside, Fellini keeps the focus on the clowns: the men behind the make-up (and they are all men here) discussing the art and illustrations of the art in action. Many of Fellini’s films burst into carnivalesque scenes of creative spectacle. The Clowns revolves around them, interspersing interviews with brief archival clips of the legends of the earlier eras and full-fledged recreations of great acts performed in a big top center ring recreated on a studio soundstage. Chaplin is referenced and Pierre Etaix, the great French cabaret clown and filmmaker, appears but Fellini’s heart is with the clowns that made that little boy cry, the aggressively crazed and borderline grotesque figures that goof in the margins of serious circus acts and take over the show in slapstick spectacles that appear as utter anarchy to the viewer.

Fellini clearly loves these figures, “the mockers and the mocked,” as he described them in the book The Clowns. Early in the film he cuts from the circus scenes of performers in full regalia to shots of the eccentrics of his little village. These are the kinds of characters you find in neighborhoods the world over, recreated by Fellini as a series of postcard gags to illustrate his take on the clown as a theatrical mirror on society’s oddballs. Ever the cartoonist, Fellini filled his films with live action caricatures, giving both his playful remembrances and satirical portraits of small towns and modern urban culture a suggestion of life as a circus in its own right. They are chorus and protagonist: tramps and roustabouts, hookers and grifters, petty bureaucrats and decadent celebrities, figures both pompous and pathetic.

The Clowns ends with a funeral, appropriately enough after this parade of interviews with aging and retired legends of the center ring, but this procession of circus jesters is an absurdist event of chaos and anarchy and slapstick mayhem. The circus of old may be dead and the classic clown a thing of the past but Fellini gives us resurrection rather than epitaph. Just like the clowns reborn as rebels and outcasts and figures of ridicule in his films. It’s a bittersweet message more complicated than it appears on the surface. More than just a documentary on the history and the culture of the clown, The Clowns is a glimpse into Fellini’s complicated relationship with this circus jester as an expression of human impulse and instinct and rebellion unleashed. Maybe that’s why the boy cried at the antics of the clowns in that opening scene. That kind of freedom and anarchy can be scary.