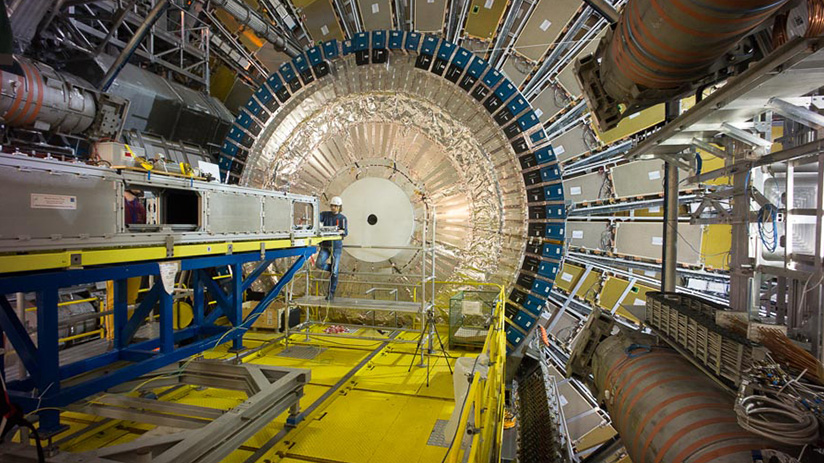

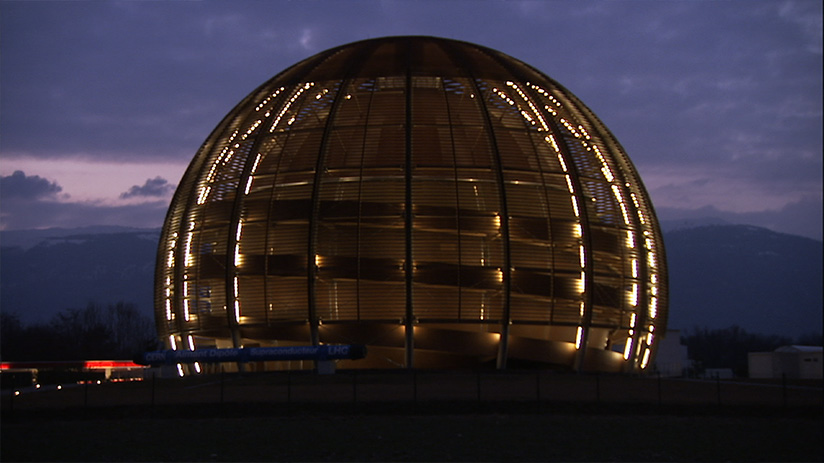

Since the Backlot sidebar was created a few years ago, dozens of wonderful documentaries have premiered at the Telluride Film Festival that otherwise might’ve been difficult to include in the forty-ish title main selection. The intimately-sized screening room at the local library allows for a perfect opportunity to see a selection of fantastic nonfiction films at one of the best film festivals in the world. For the 2013 edition, an outstanding documentary from filmmaker Mark Levinson about the Large Hadron Collider and the search for the so-called “God particle” premiered. It would be a challenge to imagine a more compelling film about any scientific subject let alone a documentary about a topic as little understood by general audiences as particle physics. Jonathan Marlow approached Particle Fever producer (as well as scientist and subject of the film) David Kaplan at the Telluride Film Festival’s annual Labor Day Picnic with the vague notion that the added publicity of an interview might help the film find a U.S. distributor. Kaplan and Levinson subsequently sat down at a coffee shop along [Colorado Avenue] to discuss their remarkable—and immensely entertaining—documentary.

Initially, the following article was intended to run in coordination with the Particle Fever screenings at the New York Film Festival. In the meantime, though, Marlow was informed of a secret: the film had been acquired but the announcement of the acquisition wasn’t made public. The interview then went ‘on the shelf’ until the announcement was finally made. And now it can be told: BOND360 will distribute the film in the U.S. It opens March 2014.

Jonathan Marlow: Inevitably, at a festival of this sort, everyone asks attendees what they’ve liked and what they should see. A number of the films in the festival I’d seen prior to arriving. Therein, the usual question—’What are you seeing here that you like?’—I tend to eliminate from contention everything I’ve seen prior to arriving. My answer this time around was, ‘You have to see this film about particle physics. I know that you might not think that this is something that is of interest to you. But it is.’ It is challenging to make a documentary about science that is accessible to audiences that could either be knowledgeable or completely unaware of the topic or perhaps somewhere in-between. You have this full spectrum. You’ve said in the two introductions I’ve attended that you felt that there could be a movie here. And events conspired to make it more dramatic than it may have otherwise been.

Kaplan: Right.

Mark Levinson: Yes.

Kaplan: Admittedly, I didn’t have any real film experience.

Marlow: But you studied as a filmmaker?

Kaplan: I did. I went to film school and then I transferred to Berkeley and decided to do physics instead because film looked harder. [Laughter.] I benefited by not being in the film world. I was not cynical.

Marlow: Until now.

Kaplan: Now I am. Now I can go back! [Laughter.] In the beginning, I would just tell my story to my friends and to my family. I said, ‘This is happening.’ At some point the story was so dramatic—and I got good at telling it—that people were floored by what was about to happen. Someone told me—it wasn’t even my idea—that I had to record it all somehow. I have never heard of a time in history where something like this happened to a field. Where the entire field depended on a single experiment or piece of data, whatever it is could end the field maybe. It was a circuitous route to deciding it was a film. At one point it was a book. I couldn’t get an author to write a book because nobody would ever buy a book about this.

Levinson: Before.

Kaplan: Before, yes. No, I understand. There was [the notion of] a ‘history of physics’ project. There were many possibilities. At some point, someone suggested, ‘Why don’t you record all the interviews you’re doing?’ I had already started doing that with a video camera. There are a lot of technical details associated with recording people on camera and I could either attempt to learn those or get a team. But I always knew that it was an amazing story but also it was an amazing set of people that I think everybody should meet. They would never meet in any other way.

Marlow: These are the individuals that we see. One of the things that is very engaging about the structure of the documentary is that you have a handful of very specific people that you follow. Yourself included.

Kaplan: The choice of me being followed was a bit ambiguous. Although we always knew that…

Levinson: On some level, I think David actually did leave that to choice to me. He had an ambivalent feeling about it.

Kaplan: What we always thought is that we wanted to save money.

Levinson: David could come in and connect the dots. We wouldn’t have to shoot for hundreds of hours until somebody said exactly the right thing.

Marlow: At what stage did you film your presentation? You see it fairly early in the film and it is a thread throughout the entirety of this documentary. You are a performer. You can present this material. It’s not a dry presentation. And that is the catalyst rest of the documentary. That personality is carried through in all of the other interviews.

Levinson: He is a performer. He’s denied it. [Laughter.] Walter [Murch, editor of the film] and I treated this as a dramatic film and we used all of the resources that we had. Which means going back and re-recording lines as well as having someone do lines and perform. We had David do this on his own. ‘No, I’m a terrible actor,’ and Walter and I would say, ‘No, you’re a great actor and it’s very compelling.’ The idea of using the lecture at the beginning was something that came very late in terms of its real use.

Marlow: As a structural device?

Levinson: The question of how to present the physics: how much and at what point? It was the hardest thing. For the lecture, we had had ideas about it. But just having a lecture is not interesting.

Marlow: Agreed. An Inconvenient Truth is a fairly obvious example.

Kaplan: Yes, although it did it insanely well. You can’t completely discount that.

Levinson: But the way in which it was eventually integrated with other things and with the lecture and with vérité. We had David’s lecture as a base but then we really tailored it. This we left to the great Walter to figure out where and then we could very carefully record the exact lines we needed to piece things together. What you see with the lecture is actually very sophisticated filmmaking as well. Starting with a great lecture, of course, but the lines are woven in and out and in and out to get exactly what we needed to say and the things that we thought we had to tell.

Kaplan: Everything is said in all the lectures and by all of our characters. But not like this. That can easily fill two hours.

Levinson: It was very technical so we also had to eventually get to a decision about what is the vocabulary that we’re going to define in this film and what wouldn’t be included. That sometimes meant identifying things with one term that other people would use other terms for. We had to be consistent. We decided that these are the terms that we expect people are going to have to know.

Kaplan: Or at least get familiar with. The dichotomy was that we also wanted the physicists to be completely themselves—honest—and say what is happening. That meant hours and hours and hours of footage of hardcore jargon.

Marlow: Which you can distill, in a sense. You can make the numbers 115 and 140 very dramatic. The anticipation of how to arrive at this information where these details will all fall in the course of the documentary.

Kaplan: We culled it down to the very essentials to create a narrative structure. We always thought that the physics would only come in as a support of the narrative and not as something in-and-of itself to teach the physics. There are plenty of other opportunities to do that. That wasn’t the goal of this film.

Levinson: With the 115/140, that dichotomy was something that nature gave us. It was a gift. We had so many gifts. Starting with the accident for us—not for the physics community, but for the film—that was nine days after the first shoot. In one sense, without that, it would have been a very different (and a lot less interesting) film. You have the accident and then it took just about a year to get going again. It was a good amount of time. Then they got a result that wasn’t right but raised the specter of all these things. Then they finally arrive at the Higgs [boson]. You can’t count on any of these things. What we get credit for is being there. For continuing. And nature gave us a lot of the ingredients to make it into something that is very compelling.

Marlow: The thing that is fascinating about that structure is that you are able to create drama. Even with what Walter Murch is able to do with the anticipation around the Higgs announcement and cutting that material together. It builds. Everyone in that audience ideally has an awareness that this was discovered. To create suspense out of something that is already known is an incredible gift. With documentaries, there are usually some aspects which the filmmakers skip. But every aspect of Particle Fever—the animation, the music, the editing, obviously, the direction—is above-and-beyond. Even the interaction with the web-cam materials. That adds an essential honesty….

Kaplan: …and intimacy.

Marlow: ‘Intimacy’ is the word I was looking for. It’s great filmmaking.

Levinson: That’s great to hear. This was always the goal. I came from a narrative background and I always had the hope that it would be like this.

Marlow: You sabotaged the collider. I get it.

Levinson: Exactly.

Marlow: It just makes for a better story.

Kaplan: You phoned it in.

Levinson: Yes. As soon as I knew which button to push.

Kaplan: The hard part was getting him to set the mass of the Higgs. You have to talk to a lot of people to get that done. That’s the heroic part.

Levinson: …somewhere in-between these two numbers. If you could do that… Snowden? That was easy. I had to get into all of these computers… [Laughter.] Luckily, they don’t imprison people for that.

Kaplan: All in the name of entertainment.

Levinson: We were really blessed with our footage. When we started our rough-cut screenings, I was astonished by the number of people who said, ‘They’re like ordinary people. They’re normal people.’ It is sad in some sense that they thought physicists were weirdoes. I think they suspected that they were egotistical, that they were supercilious. That is not the experience that I had. It is obviously not the experience David’s had. I think that was actually one of the fundamental things. We wanted to show that they’re real people, what it really is like and we got characters that everybody really….

Marlow: There is the possibility that they would say, ‘Well, sure, these people are normal. But obviously the rest of the people we see but don’t hear, those people are miscreants.’

Levinson: Do you get that sense?

Marlow: No, no, no, no.

Levinson: Do you start to wonder that?

Marlow: No, I didn’t. But I imagine that certain folks—the politicians from the U.S. in the beginning, for instance, who tried to establish that the Texas collider was a boondoggle—those people will look at it and say, ‘See? We’re vindicated.’ I am certain when the meltdown happened. ‘See? Look, at least we didn’t build a thing that broke down.’ Now, when the Higgs was discovered, others say, ‘We could have been a part of that. We’re on the sidelines.’

Kaplan: We were very anxious to get that footage in. That was one of the long stories about how to actually get that piece in about the old collider. We won’t tell the story because it’s a very long story. As far as the characters go, one of the impetuses for me was that I just wanted to share these amazing human beings with everybody. I loved Savas [Dimopoulos] and Nima [Arkani-Hamed] and Fabiola [Gianotti]. These are people who were in my world who I just thought were spectacular. What we talk about is not only technical, there’s a drive to it. I wanted people to get a taste of that. I’ve been in Savas’s office so many times where I just felt a rush of something amazing. It was just a pure joy to be there.

Marlow: Does having your mother here change anything? She can say, ‘Robert Redford, Ralph Fiennes and my son. People are coming up to my son on the street….’

Kaplan: My mother has been doing that ever since I was nobody. So whether I’m somebody or not is irrelevant! We call that ‘time translation invariance.’ [Laughter.] It’s a technical term.

Marlow: Another thing that is an interesting development in this whole process is that the collider is dormant again as they make refinements and improvements. The timing of the film actually falls in a unique place.

Kaplan: We knew it all along.

Levinson: It’s interesting because it didn’t even strike me so clearly until we were near the end. I started realizing that we could say that we filmed this period in the history of science that is absolutely unique and will not be duplicated probably in our lifetime. It was actually before the discovery and I was talking to Michael Lamont, the head of operations—the beam guy—and he was saying that he was with Lyn Evans and they were reminiscing about first beam. It’s like this is such a memory and he said, ‘God, I’m already forgetting.’ It was so amazing. There was this period of time that we lived through and he looked at me and we said, ‘Yes, we have the record of it.’ I think, as a historical record of this period and being able to have been there for all these events as a self‑contained thing, there are many other incidental ways. Fabiola is no longer the spokesperson. We had exactly when she was there. Martin Aleksa was the run-control coordinator.

Kaplan: …temporary positions. People get elected and they rose to the top.

Levinson: They rose to the top there. Monica [Dunford] was asked to give that talk after [we started working with her]. I was just was getting to know Monica at the time. There were a lot of things about it that happened in this period of time that were remarkable. When do we end the film? You don’t know what is going to happen. Do you end it with an accident? That would’ve been a real downer. Do you end it when it first starts up again? But the actual re-start was very low-key. They were very fearful of it being a media event. It didn’t feel like an end of a film. We could have ended it with high-energy collisions and we really thought about that. That was going to be the end for a while. But then when David started saying, ‘I think we might be getting some results,’ I thought, ‘Oh, no [here we go again]….’

Marlow: Because there is the desire, when you’re working on a project, to have it end somewhere. In a way, it is very tempting to prematurely close it. You talked yesterday about submitting this to Telluride last year. You mentioned that Tom Luddy, at the time, said that the documentary needed a third act.

Kaplan: But, at that point, we already knew.

Levinson: We already knew it was coming.

Kaplan: It was coming and we didn’t have it, yes.

Levinson: Exactly. Once it did come, it required some rejiggering dramatically to get to that point, and the consequences of what it would mean. That’s the other…

Kaplan: You were editing for ten months after that.

Levinson: Having the machine shut is great for when the film comes out. [Laughter.] We know that we don’t have to worry.

Kaplan: You don’t want to compete with press of actual discoveries.

Marlow: If you’re just a document of a thing that happened in the past, you’re no longer relevant. That’s always the challenge of a documentary, particularly about science. The moment the film is finished, things have already moved far beyond the ending. I was relatively aware of almost everything that occurs in the film but I had never seen the actual footage of the accident. It is much more horrific seeing those photos than I ever imagined. The extent of the repair was obviously a big endeavor but seeing the exact extent of the accident was really shocking.

Levinson: It may shock some people at CERN that I have some of that footage.

Marlow: I wondered about that. Any organization that would do first beam on, in European order, 10.9.08, would seem a little pretentious. There are some perception issues and the management of those perceptions. That’s a challenge.

Kaplan: Absolutely.

Marlow: They seem somewhat obsessed by what gets out and how it’s presented. You see a little bit of that with the interchange between Fabiola and….

Kaplan: Katie. She’s coming from the press office there.

Marlow: ‘These people will be very upset if they’re not here for first beam….’ They seem to be missing the whole point of how this works.

Levinson: Right.

Kaplan: That aspect was great. I mean all of that was great because it was very uncomfortable for them and you always want some type of conflict. This was a kind of conflict that was very true and palpable. On the other hand, you know, you cannot contain thousands of people. And Mark got to know enough of those people that it didn’t matter how hard they clamped down. You were going to get in and people were going to say the truth and it didn’t matter. Because most of those people act as scientists and scientists are in the truth business. There’s no use in telling a story because you’ll be called wrong at some point. And that’s the last thing you want.

Marlow: Right. It’s very difficult to ‘spin’ science. It either is or it isn’t.

Kaplan: Yes. In that sense, it was much easier to get in than you would’ve expected. Even with that whole front that they were holding onto.

Levinson: They were incredibly open. They saw what we were doing. We were sort of regarded as the inside team. Literally, they became my collaborators in many ways.

Kaplan: We were the inside team.

Levinson: Were you at the Q&A when I was talking about those pictures of the accident and the whole episode? I can’t remember…

Marlow: It might’ve been one of the earlier screenings. It wasn’t at the one that I attended.

Levinson: Because, you know, there was something interesting with that. I literally was there….

Kaplan: I don’t know if we should be telling this story. I don’t think we should.

Levinson: I don’t know.

Marlow: I can excise this part. This part is off-the-record.

[Snip.]

Levinson: The bottom line is, ultimately, they were very open about it all. Individually, you know, and institutionally.

Kaplan: And Mark was drawn towards the most open people, of course.

Levinson: Right. Yes.

Marlow: This film clearly will make people more passionate about science. That’s obvious.

Kaplan: That’s what is happening.

Marlow: Will it also help to realize your dream of a larger collider? Is that a secret notion….?

Kaplan: Not a secret notion…

Marlow: I’m jesting. That would be great if that happened, though.

Kaplan: I mean, yes. Let’s hope.

Marlow: If people see the importance of this discovery and realize, ‘If the current collider gets us this far, what if we could do something even larger….’

Kaplan: Right. I think the system is fucked up enough that even if this is the biggest blockbuster in the history of documentary film, it will not get a larger collider out of the United States.

Marlow: Out of the United States, correct.

Kaplan: Yes. Will we get a larger collider worldwide? Maybe the film will help incrementally but it certainly wasn’t a goal of the film. The goal of the film was to allow scientists and everybody else to be integrated into one people.

Marlow: A unified field theory of cinema?

Kaplan: A unified field theory of humankind.

Levinson: Good use of that.

Marlow: I just thought I’d work that in. I was saving it for that moment.

Kaplan: With that ending, it could be any moment.

Levinson: It seems like you have an understanding of science. Is that true?

Marlow: I was one of the people that raised their hands when you asked the audience if they were interested in science. It is something that I am passionate about. There is a reason why I cornered you at the picnic and said, ‘Let’s sit down and talk.’ I want people to see this film.

Kaplan: So do we!

Marlow: It is really important because Particle Fever does what far too many films fail to do. You engage the audience on a fundamental level and make them understand why this issue is important. In this culture, everything tends to be evaluated by its commercial potential. Whether it is a film, whether it is a scientific discovery, whether it is art. And that is not an intrinsic aspect of what is happening here. What we get from these discoveries is something that we cannot fully comprehend today. Not in economic terms. We have to embrace knowledge on its own terms. To think of things in terms of its financial viability misses the point.

Levinson: It is fascinating to me to see the variety of the audiences at these screenings. There are many people out there that really are curious about these things. Mostly, I grew up with people who would say, ‘I’m not a science person. I don’t want to know any of this stuff.’ It turns out that there are a lot of people that want to know. They want to see it accurately portrayed. They don’t want a dumbed‑down version. Somebody was talking to me here at the festival about the fact that they wanted to see a film of substance that actually makes you think as well. That’s really rewarding. This may be a distorted environment at Telluride…

Marlow: Yes. Telluride can distort things somewhat.

Kaplan: Yes. For sure.

Levinson: But it is encouraging to see that there are a lot of people out there who are willing to go to a film not knowing anything about physics. At every screening, there have been a substantial number of people that don’t know anything about physics. They’re just there.

Kaplan: Haven’t shown any interest in the past.

Levinson: Yes, exactly. And that is fantastic.

Marlow: When you see the data coming in, particularly with the animation, there is a certain beauty to it. You have an emotional connection to what you’re seeing which you wouldn’t necessarily expect. The challenge—and the reason why I wanted to talk to you—is to help people ‘understand what they don’t understand’ which is, stated differently, to get them to know that they’d find this film of interest even if they have little interest in particle physics. The process of getting there is still riveting even if they know in advance how it ends.

Kaplan: I think that Mark is right. I like what he does when he is introducing the film and he asks [about the knowledge level in] the audience. It really does feel like there are a factor of ten or one-hundred more of you out there, but that that ninety-nine percent at some moment decided they were not good at physics, not good at math, and had some feeling that they would feel stupid or bad if they kept thinking about it. As a physicist, ‘What do you do?’ ‘I’m a particle physicist.’ ‘Oh God, I was terrible at physics but I think it’s fascinating.’ I think that there is just something to soften there where people think. You don’t have to feel stupid and you can be a part of it. You can ask any question you want and nobody is going to get mad at you. You deserve to know it. As human beings, we have a responsibility to try to figure out what we can know.

Marlow: When there are more examples of the shirt that Walter had with the Higgs logo at the center [ed.: Which Mark Levinson was wearing at the time…], I will be one of the first people to buy it.

Levinson: Great.

Marlow: Also, at the chalkboard, which I think is you, David, or might be your friend… I cannot recall. There is a drawing where it says, ‘MLMR’ with the dotted lines and the circle in the center. Is that Nima?

Kaplan: That’s Nima.

Marlow: That’s would make a great shirt as well.

Kaplan: That is a very subtle!

Marlow: It is shown twice. It’s at the end, of course, but it also is seen earlier when Nima first appears.

Kaplan: Right. We both have long hair. If we have our back to the camera… I remember you telling me it was problematic…

Levinson: That’s why we tried to put them in the last scenes together. People could realize…

Marlow: …that there are two of them.

Levinson: Didn’t you always say that—once the film came out—you’re cutting off your ponytail?

Kaplan: That was my plan. And then it was suggested that I should wait until the publicity period is over so that people could recognize me!