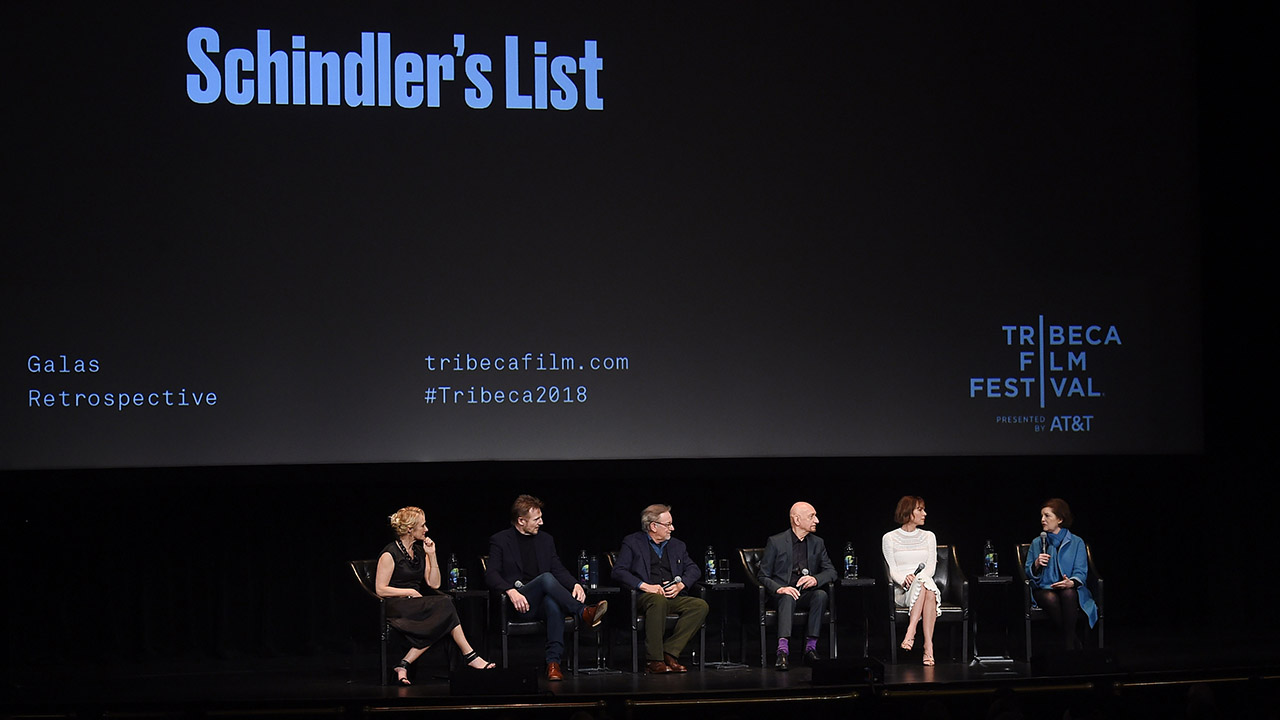

A recent survey found that the Holocaust is fading from memory. In what turned out to be an almost prescient coincidence, on April 26 the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival organized a screening honoring the 25th Anniversary of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. The screening, at New York City’s Beacon Theatre, was followed by a Q&A with the director, along with cast members Liam Neeson, Sir Ben Kingsley, Embeth Davidtz, and Caroline Goodall. The experience highlighted not just the importance of remembering the Holocaust, but also the role that film plays in translating history and committing it to memory.

The film, written by Steven Zaillian and based on a 1982 book by Thomas Keneally, takes place near the end of World War II and follows a German war profiteer, Oskar Schindler, as he gradually resolves to protect and save his Jewish factory workers from persecution and murder by the Nazis. During the Q&A, Spielberg and the cast reflected upon what it was like seeing the film today. Spielberg hadn’t seen it with an audience in twenty-five years but said that it felt like five. Kingsley commented on the power of experiencing the film in a theater again, and how meaningful it is for a large group of people to be ambushed by the “hideous logic” of the Holocaust.

The screening encouraged Spielberg and the cast to delve into their own memories of the production. Spielberg recalled reading the script, crying, and deciding that Schindler’s List would be his next film, even though he was already preparing for Jurassic Park (both films were released in 1993). He expedited Schindler’s List’s production process so that the filmmakers wouldn’t miss their window to shoot during the Polish winter. And, at least initially, in what must have felt like an incredibly surreal period in his life, he resented having to split his time between processing the nature of the Holocaust and approving models of Tyrannosaurus heads.

Spielberg also recalled how nervous he was over the prospect of people dismissing his work on the film because, thus far, he was known for making very different kinds of movies. Neeson added that in the over fifty films he’s been in since Schindler’s List, he has never seen a director as nervous as Spielberg was during the early days of shooting. Neeson struggled with his own nerves, too. At the time he was cast, he was a blossoming stage actor. He said that he finished a play in New York on a Sunday and, by Wednesday, was on location at Auschwitz. The raw power of the situation hit him all at once when Branko Lustig, one of the film’s producers- and a Holocaust survivor himself, pointed out the Auschwitz hut that he had been placed in during the war.

In many ways, Spielberg noted, making the film was an act of experiencing trauma. In one scene, Nazis rush a crowd of Jewish women into a bathhouse where crying and petrified, they aren’t sure if they are going to be gassed to death, or showered with water. In moments like these, he said, the actors weren’t pretending. They were truly experiencing what real people went through, which made the scene that much more challenging and heartfelt. To cope with the emotionally wrenching demands of the film, Spielberg said, he had Robin Williams call him long-distance from San Francisco to Poland once a week to do a fifteen-minute stand-up set. He also watched a lot of Saturday Night Live.

Winning numerous Oscars for Schindler’s List didn’t constitute a celebration, Spielberg said. It was nice to be awarded but, at the same time, the film’s significance ran much deeper. He commented on the recent news, that young people know less and less about the Holocaust, arguing that it’s a travesty that teaching youth about the Holocaust is technically optional in our educational system. It should be compulsory for every school across the country.

The implications of this education (or lack thereof) cannot be understated, and it’s about more than just paying respect to the lives that were lost. If people aren’t aware of the extent of the evil that constituted the Holocaust and have no knowledge of the magnitude of the suffering that transpired, who’s to say that history won’t repeat itself? Such hate is, sadly, never far off. Even during shooting, Spielberg and the cast and crew were frequently met with anti-Semitic hostility. Upon seeing Ralph Fiennes in his Nazi uniform, for example, an elderly Polish woman called out from her window and told him how nice he looked, adding that she wished people like him were still around to protect her.

By the end of the anniversary screening, the sounds of sniffles, blown noses, and audible crying echoed throughout the Beacon Theatre. Schindler’s List is over three hours long, and though the performances and filmmaking are masterful, it remains a difficult film to watch. Spielberg reiterated how essential it is for people to see the film, to remember the Holocaust, but that can be a difficult demand to fulfill when recalling means having to explore and re-experience the trauma.

During the Q&A, Sir Ben Kingsley referenced the famous thinker George Steiner, paraphrasing his assertions about the limits of language: Part of the difficulty in sharing the experience of the Holocaust, in communicating its significance to younger generations, lies in the fact that, at a certain point, language breaks down. There’s only so much that words can express about what occurred before they become ineffective.

But, Kingsley added, therein lies the importance of the cinematic medium. With Schindler’s List, he said, Spielberg was able to communicate the nearly incommunicable. Films like Schindler’s List have the power to timelessly relate the tragic story to young people. As long as the silver screen exists, so remains the ability to speak to those who are willing to listen, and to watch. Hope is far from lost, for there’s one more worthwhile observation to be made about the screening: It was sold out.