“Illegal drug traffic must never be presented.” So states the Motion Picture Production code instituted in 1930 by the so-called “Hays Office.” (Will Hays being the film industry’s head censor.) The office also issued a number of other declarations, including: “The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld.” “The technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.” And “Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown.” These quaint notions were rigorously enforced until the late 1950s, when films as varied as Anatomy of a Murder, Suddenly Last Summer, and most amusingly Some Like It Hot flew in face of the code’s sexual squeamishness in general, and in the case of Billy Wilder’s masterpiece the insistence that ”Sex perversion or any inference to it is forbidden.” (i.e., the film’s last line, “Well, nobody’s perfect.”) As for drugs, the first anti-code salvo was made in 1955 by Otto Preminger with his adaptation of Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm.

The savvy producer-director released this dark drug addiction drama without a “code seal” knowing full well that theater bookers wouldn’t shy away from a movie starring Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak, “code’ be damned. The Man with the Golden Arm was a box office hit garnering three Academy Award nominations, including a Best Actor nod to Frank Sinatra.

Apparently dialogue that included the word ‘shit’ (referred to off-handedly as addict argot for heroin) was going too far for those tender gatekeeper souls. Clarke and company decided to defy the state, opening the film on October 3, 1962, at the D.W. Griffith theater in New York. It was closed by the police after two matinee screenings that same day. The print was confiscated and projectionist was arrested.

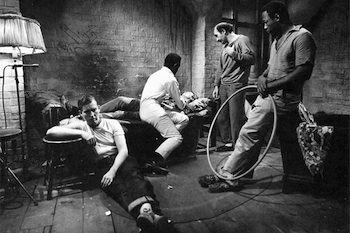

But Shirley Clarke wasn’t a Hollywood big shot like Otto Preminger. She was an independent filmmaker with at that point only a clutch of well-regarded shorts to her credit. Adapting Jack Gelber’s drama The Connection to the screen in 1962 was a logical next step in her career. This slice of junkie life, observing a crash pad of bohemian musicians waiting for their drug dealer much like Beckett’s tramps waited for Godot, wouldn’t, objectively speaking, seem to be that big a deal in regard to censorship. It’s not a slick Hollywood production. It doesn’t feature any stars, and wasn’t designed for the sort of mass release that Preminger specialized in. But things most certainly turned difficult for The Connection. Completed in 1961 Clarke and producer Lewis Allen spent a year fighting the New York State Board of Regents. (States in those pre-MPAA ratings days had censorship boards of their own.) The Regents declared that The Connection was obscene.

Apparently dialogue that included the word “shit” (referred to offhandedly as addict argot for heroin) was going too far for those tender gatekeeper souls. Clarke and company decided to defy the state, opening the film on October 3, 1962, at the D.W. Griffith theater in New York. It was closed by the police after two matinee screenings that same day. The print was confiscated and projectionist was arrested. The court fight went on, but by the time a ruling came down in the film’s favor it had lost momentum. Jonas Mekas had come to Clarke’s defense in the Village Voice but Bosley Crowther in the all-powerful New York Times had declared The Connection “a forthright and repulsive observation of a sleazy, snarling group of narcotic addicts,” so that was that as far as the U.S. was concerned. It didn’t condemn drug the way Preminger’s film did—and was therefore condemned.

Jonas Mekas had come to Clarke’s defense in the Village Voice but Bosley Crowther in the all-powerful New York Times had declared The Connection ‘a forthright and repulsive observation of a sleazy, snarling group of narcotic addicts,’ so that was that as far as the U.S. was concerned. It didn’t condemn drug the way Preminger’s film did—and was therefore condemned.

In Europe where The Connection premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, it fared considerably better, its matter-of-fact treatment of narcotics addiction and its innovative use of the plan américain (the medium long-shot that made Howard Hawks an idol of the French) impressed many—especially Jacques Rivette who used this technique to great effect in several of his films, particularly his masterpiece Out 1. But in its home country, The Connection has remained cinema non grata until perhaps now. For it is hoped that the revival of Clarke’s first masterpiece (opening with a new 35mm print restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles on July 20 prior to DVD release) will put The Connection in its rightful place in American independent film history and inspire a new generation to think of film differently.

Written in 1957, The Connection, as a play, became the first great success of Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s The Living Theater. The simplicity of the curtain rising on a coldwater flat where a clutch of characters interact casually in a narrative that eschews both conventional dramatics and conventional morality proved a revelation. For rather than simply denigrating drugs a la A Hatful of Rain, The Connection shows it as part of life. No character gets on a high horse to attack it, and no eleventh-hour intervention of the police arrives to deliver a “crime doesn’t pay” denouement. Audiences flocked to it both in the U.S. and Europe. Winning the 1959-60 season Obie award for best play and best actor (Warren Finnerty), it won the Vernon Rice Drama Desk Award and was performed over 722 times. But Gelber’s play was one thing and the film Clarke made of it is quite another.

Two of the characters in Gelber’s original play were theater professionals visiting the junkie’s den in order to learn firsthand about the addict’s world and making plans to stage a play about it in the future using “real” addicts. Clarke had Gelber rewrite these characters as a film crew with a director (William Redfield) and a camera assistant (Roscoe Lee Browne) filming the goings on as a cinéma vérité documentary. In other words the film we’re looking at is the fruit of these fictional characters’ labors. Hence in a single master stroke Clarke transforms theatrical space into cinematic space. One camera is the “master shot” plan americaine, while the other, which is hand-held by the director character, offers close ups. As a result the characters in the film look into the camera and speak directly to the audience in an offhanded way looking forward to Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls and late period Cassavetes works like Opening Night (whose dealings with the theatrical are quite comparable to Clarke’s). And that’s not to mention Rivette, especially in the sequences of Out 1 revolving around Michel Lonsdale’s troupe and its freewheeling improvised version of Prometheus Bound.

Yet for all that has come in its wake there remains a freshness to The Connection in everything from Living Theater veteran Jim Anderson’s off-hand cool, Jerome Raphael’s hipster-philosopher musings, and Warren Finnerty’s hysteria as the sexually unsettled Leach (more than one of his friends regard him as a closeted gay) who provides the film with an unsettling climax when he complains to Cowboy (Carl Lee), the ultra-slick drug dealer (ie. “connection”), that he hasn’t given him enough of a shot. So Cowboy complies by letting him have another—leading to an overdose that nearly kills Leach. This in turn underscore Clarke’s decorousness. For in the film’s last quarter, Cowboy has the junkies retire to the off-screen space of the apartment’s bathroom to get their shots. Leach is the only character we see giving himself an injection. Thus we “see it all” but not so much as to turn The Connection into a shallow peep show, and executed in such a way as to leave us asking more questions rather than offering simplistic answers.

For Clarke, moviemaking was ‘a matter of life and death.’ She wasn’t ever about to sacrifice her hard-won life. But the “near death experiences” she puts on display in The Connection shows just how close to the bone it all was for her, and for anyone who really cares about film.

Shirley Clarke had less trouble with her next feature, The Cool World (1964), about Harlem teenagers and her documentaries Portrait of Jason (1967), about a hipster/hustler, and Ornette: Made in America (1985), about jazz great Ornette Coleman. But she has never been afforded the acclaim she has so richly deserved, so one can only hope this re-release will right that wrong.

In Agnès Varda’s freewheeling comedy Lions Love (1969), Shirley Clarke appears as herself, enacting a scene in which she tries—and fails—to get backing for a project. Varda wanted Clarke to end the scene by aping a suicide attempt. Clarke balks at the notion, so Varda does it herself in her stead. It’s a darkly amusing scene, but it underscores a truth that Varda knew. For Clarke, moviemaking was “a matter of life and death.” She wasn’t ever about to sacrifice her hard-won life. But the “near death experiences” she puts on display in The Connection shows just how close to the bone it all was for her, and for anyone who really cares about film.