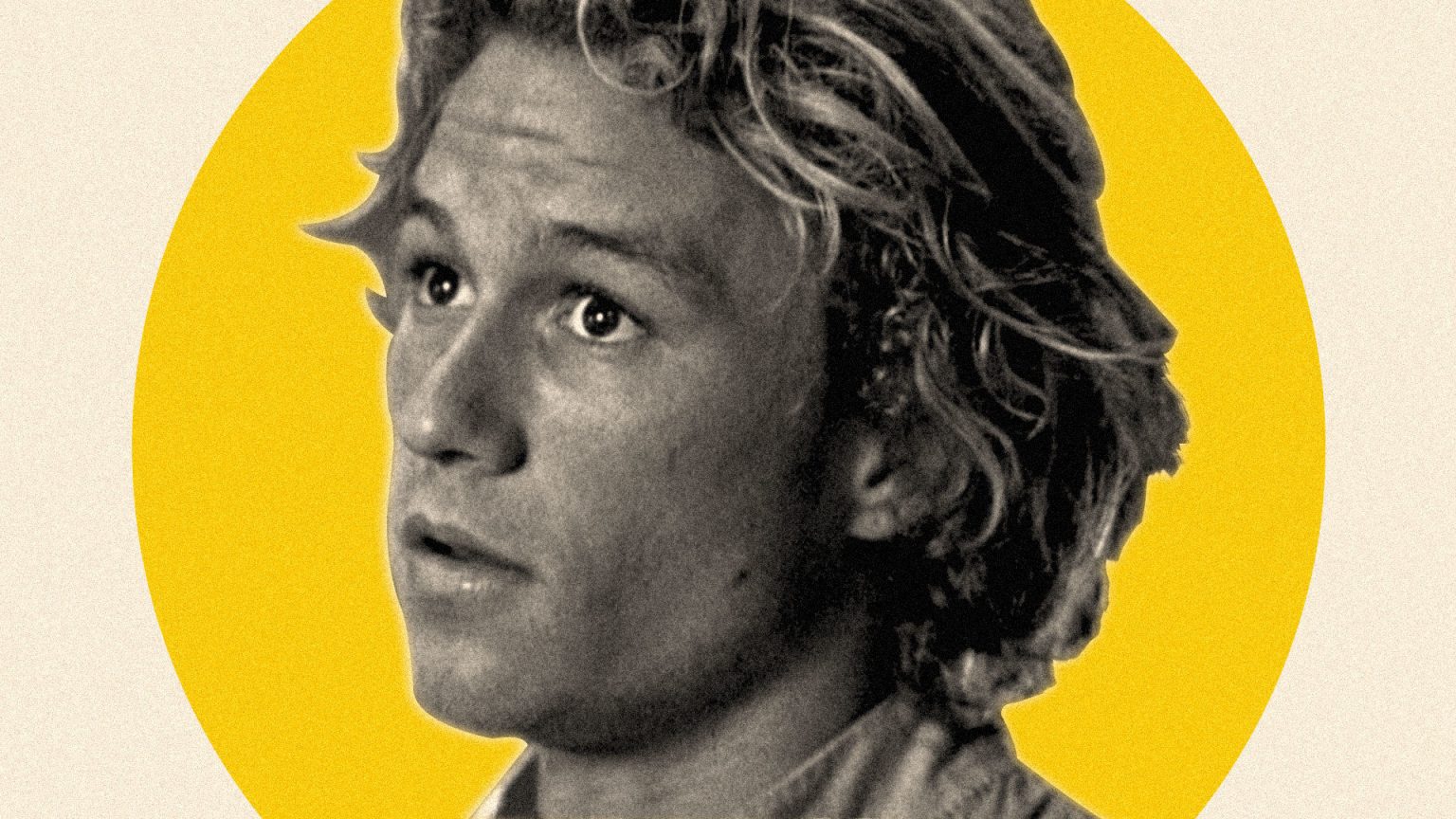

Today would have been Heath Ledger’s thirty-ninth birthday. He was born in Perth, Western Australia. At age ten, he starred in a school production of Peter Pan. He later won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of the Joker in The Dark Knight. Of acting, he said, “I don’t even want to spend the rest of my life doing this in this industry. There’s so much more I want to discover.” He died unexpectedly on January 22, 2008, at age 28.

On that day, I was sitting in a basement screening room attending a class on the history of French film. I was bored. It had snowed recently. Ask me a week from now what I ate for breakfast today, or whom I stood next to on the subway, and I likely won’t remember. But I do recall, in surprising detail, the day that Heath Ledger died. A friend with whom I hadn’t spoken in a while texted me with the news. When I left the academic building, the late afternoon winter sky was deep blue, set against the campus’s sodium lamps. Why does this moment stand out like a scene in a movie?

The loss was an undeniable shock. Heath Ledger was a preternaturally gifted actor, and relentlessly watchable. He was young and handsome, mysterious and charming. He had a partner in Michelle Williams and a young child. He was poised for a meteoric career trajectory. Then, suddenly, he was gone. His characters were always so assured, so reliably confident.

It’s those characters, coupled with the shock, that further define the feeling of loss. After all, the vast majority of us didn’t know Heath Ledger personally. What I knew of him I knew through his roles, in the films of his that I watched. I was ten, for example, when 10 Things I Hate About You came out. My older sister had a crush on Ledger’s character, Patrick Verona, which I didn’t entirely understand. I did, though, like the scene where he and Kat (Julia Stiles) go on a paintball date. Listening on CD to the song that plays during that scene (FNT, by Semisonic), I wondered what it would be like to go on a date. I also resolved to one day serenade someone in front of a crowd of strangers with “Can’t Take My Eyes Off Of You,” just like Patrick does. When Heath Ledger died, it felt like Patrick Verona was gone, too, along with all of the other characters I’d seen him play. There would be no more new films to relate to, just the shortlist that he gave us. In lieu of a new romantic comedy, I would have to re-watch 10 Things I Hate About You.

It would be a mistake, though, to let the weight of the tragedy define the memory of Heath Ledger, and the meaning of the loss. Though it is upsetting that there are only so many Heath Ledger films, each one will always offer the opportunity for new insight. I have, indeed, re-watched 10 Things I Hate About You more times than I can possibly count. My more mature self now completely understands why my sister loved Patrick Verona. From time to time, I listen to FNT, and I wonder if maybe I should cheesily serenade my girlfriend at some point. It’s a lighthearted movie, not necessarily meant to be thought-provoking, but every time I see it, every time I watch Ledger on screen, I can’t help inadvertently confronting the ways in which I have evolved since the last viewing. On January 22, 2008, I was a confused, anxiety-ridden college student. Today, I’m an adult with a completely different set of challenges. Revisiting the news of Heath Ledger’s death, like revisiting his films, I discover more about myself.

“There’s so much more I want to discover,” he said, and it’s in that spirit that he should be remembered. It’s through that sense of discovery that his story goes on if we let it. Like other performers who have passed away before their time, Ledger lives on in his characters. Their onscreen stories remain the same, but in experiencing them again there will always be something new to find. As long as Heath Ledger’s films exist, he’ll be a source of discovery. It may not be the exact discovery we wish could have happened, but it’s nonetheless a way for him to transcend the tragic legacy of his untimely death. It’s a way to consider him living on, not in the afterlife, but in yours.