There’s an unofficial shortlist of essential film-critic compendiums represented on my bookshelves. Whether collections of essays, histories, or even intensively annotated catalogs, they read like literary equivalents of classic albums, compelling and standing up to repeat spins and needle drops, with expansive and idiosyncratic perspectives on often underappreciated genres, movements or cinematic outputs redefined—and made to feel newly discovered—through the writer’s own aesthetic prism. Some all-time bangers include Amos Vogel’s indispensable “Film as a Subversive Art” (reissued last year by Jake Perlin’s Film Desk), Carlos Clarens’ “Crime Movies” and Jonathan Rosenbaum & J. Hoberman’s “Midnight Movies”—which in 1991 created a unifying context for the outré visions of rogue auteurs like David Lynch, Alejandro Jodorowsky and John Waters.

When the Canadian writer, critic, historian and programmer Kier-La Janisse published “House of Psychotic Women” 10 years ago, there was a new title to add to that list. Her subtitle, “An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films,” sounds a bit academic, but the approach is so much more unexpected and original. Throughout 447 pages of the newly reissued edition (FAB Press), which includes an extensive image gallery and a 200+ page commentary appendix expanded to include more than a hundred new films released in the past decade, Janisse uses her own complex, chaotic and often traumatic personal story to explore and explain her love for hundreds of films centered on women in the grip of various elements of psychosis. As she declares in the introduction, “[M]y starting point was a question and that question presented itself easily: I wanted to know why I was crazy—and what happened when you feed crazy with more crazy.”

Well, you end up with this book, which has garnered its own cult following and such disparate, notable fans as No Wave punk pioneer Lydia Lunch and 1980s teen-movie queen Molly Ringwald. Although Janisse has been prolific on multiple fronts—most recently as director of the acclaimed folk-horror documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched—this wrenchingly intimate treatise connects on a more profound level with its readers. The author’s rigorous research isn’t only a deep dive into the uncharted murk of psychosexual genre film, which constitutes endless cross-categories, from brain-melting Italian giallo thrillers and grindhouse sleaze to made-for-TV melodramas and the work of canonical auteurs like Antonioni and Altman. She is also as doggedly analytical about her own psyche, her direct and unfussy prose driven by a clear-minded candor that can knock you breathless as surely as the most pulse-quickening scenes from one of the films discussed.

Janisse doesn’t waste time. In the book’s first pages she relates a shadowy memory, the very first thing she remembers from childhood. One day she learns from an aunt that the mysterious incident was that of her adoptive mother’s sexual assault, which she had just interrupted, causing the rapist to flee. Janisse pivots from this disturbing account into a discussion of The Entity (1982), a still-potent supernatural drama, based on a true story, starring Barbara Hershey as a woman who is repeatedly raped by an invisible assailant: a ghost. Medical professionals balk. As did Janisse’s father, a psychologist who discounted his former wife’s claims.

Movies open trapdoors into harrowing but revelatory personal reflections (and vice-versa) as Janisse crafts a serialistic cliffhanger about her coming-of-age as a young woman and a cinephile. In the process, she curates her own canon, literally hundreds of films deep, taking us from the Spanish thriller that lent her book its title (also known as The Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll) to the insane world of Staten Island filmmaker Andy Milligan (The Rats Are Coming! The Werewolves Are Here!) ,obscure ’70s psych-horror like The Mafu Cage—a rare feature from writer-director Karen Arthur, with Carol Kane and Lee Grant as extremely weird sisters—to more talked-about selections like Ken Russell’s The Devils, Takashi Miike’s Audition, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist and Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession, whose iconic poster art also served as the cover of the book’s original hardback edition. (The new edition reproduces the softback cover image, a still from Dr. Jekyll and His Women, from fellow Polish provocateur Walerian Borowczyk). If that should prove somehow insufficient, all those films and many, many others are addressed in the book’s final section, “Compendium of Female Neurosis,” which dutifully includes a ton of features released in the years since the first edition was published (from Always Shine to Woodshock).

“I realized, if I’m going to tell these stories and say I can relate to the character from The Piano Teacher, I have to explain that,” Janisse has said about why she wrote the book the way she did. “That’s going to mean telling some personal things that are going to be hard to talk about. I have to be honest. Otherwise there’s no point in doing it. In order for people to really understand what I get out of these movies, how they’re important to me and how they’ve actually helped me in lots of ways in life, I have to be honest about what that life has been.”

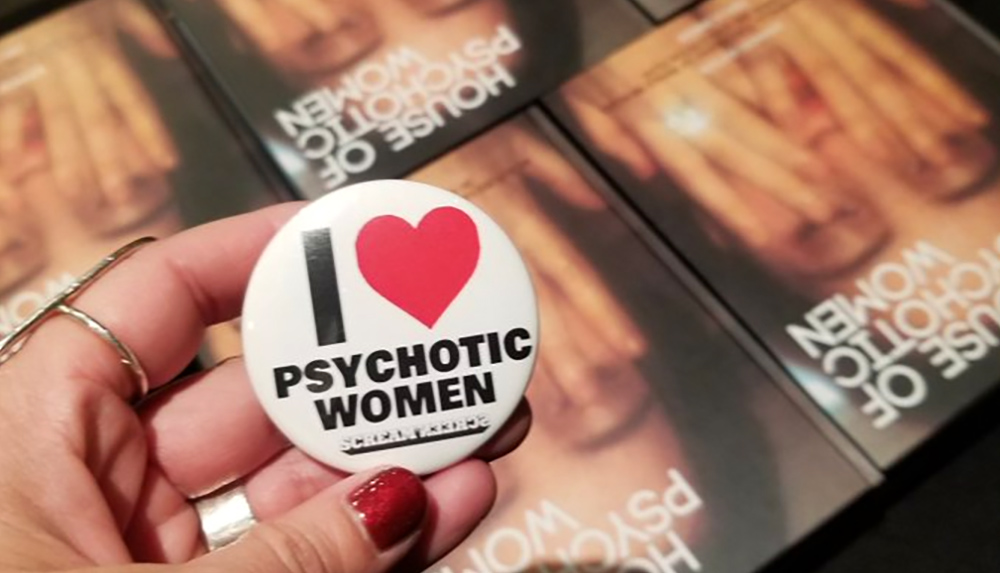

(Top photo from Denver Film’s “Weekend of Psychotic Women” event (Sep. 2022), taken from Kier-La Janisse’s Twitter.)