The title to Ned Thanhouser‘s documentary, The Thanhouser Studio and the Birth of American Cinema, isn’t mere hyperbole.

Veteran stage actor and theater manager Edwin Thanhouser (the director’s grandfather) made his move from live theater to making movies for the growing market of cinema in 1909. By 1918, as the industry grew beyond Thanhouser’s ability to keep pace, he closed it down. In those nine years of the studio’s existence, a period in which it produced over 1,000 shorts, features and serials, the industry changed dramatically. The stranglehold of Patents Trust over the fledgling industry was broken, short films gave way to features, the center of filmmaking relocated from New York to California, Hollywood was born, the grammar of narrative filmmaking evolved from tableaux scenes and simple continuity editing to complex patterns of shots to tell complicated stories, and the reign of the studio brand gave way to the birth of movie stars.

According to the film, which is guided by historical research of Q. David Bowers, Thanhouser accounted for twenty-five percent of the independent films made in the United States at the peak of its success. The Thanhouser brand was a recognized mark of quality to audiences and distributors alike and two Thanhouser shorts, The Cry of the Children (1912), which addressed child labor in American factories, and The Evidence of the Film (1913), one of a number of Thanhouser films that incorporates the filmmaking process itself in the storytelling, were selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. Yet only a few years later, the once-vibrant Thanhouser was in danger of becoming old-fashioned and behind the times. The story of Thanhouser is in the story of the rapid transformation of American movies in the most creatively and commercially dramatic era of American cinema.

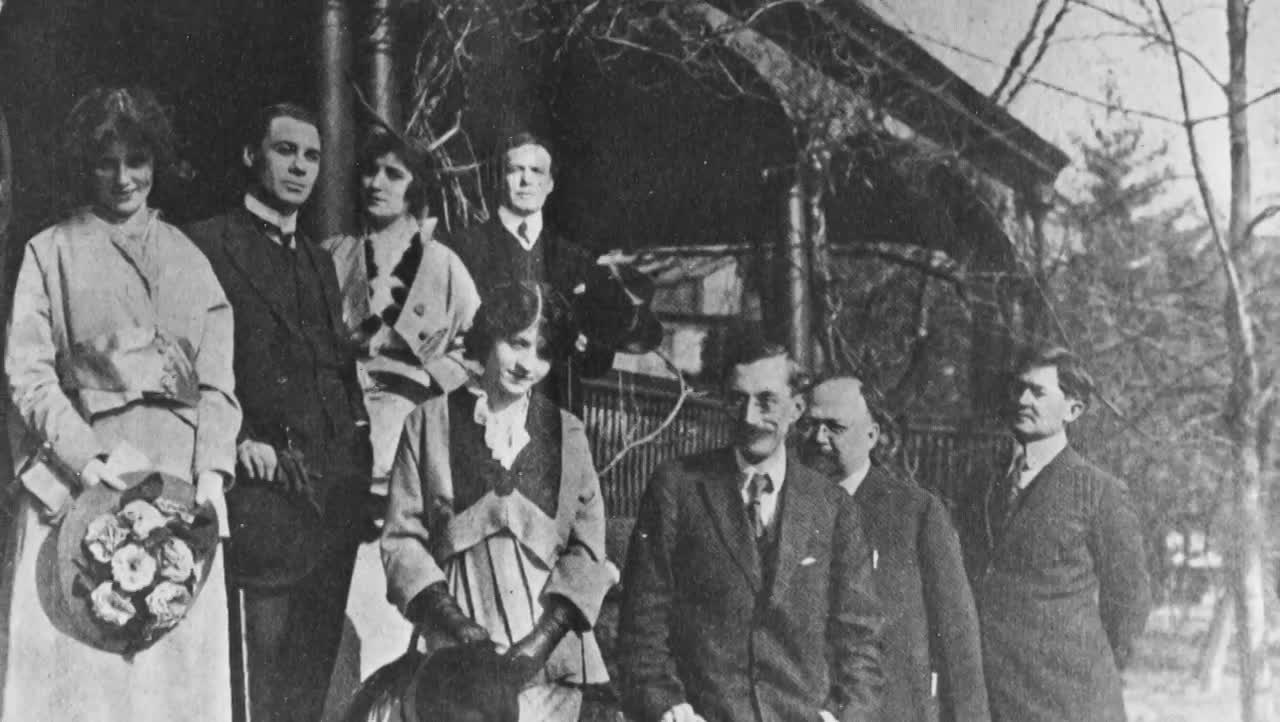

The Thanhouser Company was formed by Edwin Thanhouser in New Rochelle, New York, with his actress wife Gertrude Thanhouser and brother-in-law Lloyd Lonergan, a newspaperman who took charge of writing the scenarios, in 1909. This was the wild frontier of the industry, when entrepreneurs would take a look at the fledgling industry and decide to take their own shot at making movies. And like the American frontier of old, the independents were often at the mercy of the industry’s answer to the cattle baron, in this case the Motion Picture Patent Company, which claimed a monopoly over the machinery of motion picture.

Edwin Thanhouser was an outsider to the Patent Trust and to the industry as a whole. He came from the legitimate theater so, to compete with established studios like Biograph, Essenay, and Vitagraph, Edwin turned to theater contacts for his casts and directors. Edwin had never produced a film and his first directors had never directed for the screen before, only for the stage, yet they evolved remarkably quickly as filmmakers. Edwin’s intelligence and ambition and his commitment to storytelling and innovation guided the studio’s output while his collaborators brought the values of theater to the screen as they all found their way into moviemaking.

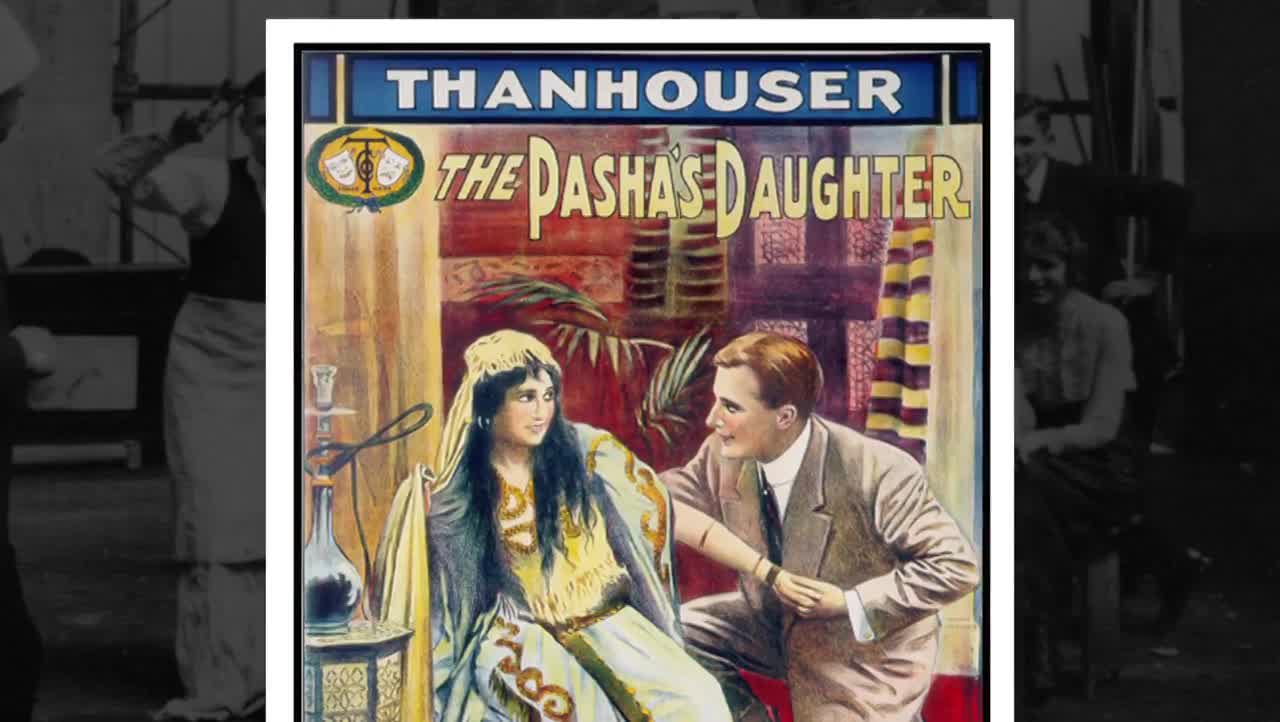

They found success with a pair of child stars, designated The Thanhouser Kid (eight-year-old Marie Eline) and The Thanhouser Kidlet (six-year-old Helen Badgely) in the pre-movie star days, a pack of studio dogs (including Shep, The Thanhouser Collie), and most importantly a spunky leading lady named Florence LaBadie and known to the public as Fearless Florence for her daring stunts (she performed most of them herself). Along with comic stories and spirited adventures (many with the company dogs rescuing the Thanhouser tots), they took on literary stories and the works of Shakespeare and Ibsen, presented a more subtle and naturalistic style of acting, and delivered production value on the screen with elaborate sets and costumes. Gertrude took a major creative role as a pioneering production and costume designer before such terms were ever used to the filmmaking business.

You might expect stagey, theatrical productions. In fact Thanhouser films are vibrant and lively, with often complex stories, effective staging in depth and creative camera angles and lighting. They made a specialty of simple but effective special effects, such as the superimpositions for the transformation in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1912) and created dramatic images with night-for-night shooting in the Civil War film Their One Love (1915), a one-reel drama with a more dynamic visual style than even Griffith‘s battle scenes in The Birth of a Nation. They were innovative marketers, releasing the three-reel biblical spectacle The Star of Bethlehem (1912) as a Christmas event on December 24. It was a huge success, critically and commercially. And they were modern. Look at Petticoat Camp (1912), a battle-of-the-sexes comedy with a contemporary sensibility and a spirited sense of fun. Thanhouser quickly established itself as the most sophisticated of independent studios.

While they lavished attention on film sets in their roomy studio, they also took their cameras on location in the nearby countryside and city. Scenes from the child-labor drama The Cry of the Children (1912), inspired by the poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, were shot in real factory, with scenes of moppets working under harsh conditions contrasted with shots of the factory owners in lives of comfort, a simple but effective editing dialectic that Eisenstein would develop a decade later. And at the peak of their success, they built sister studios in California and Florida, which expanded their access to locations and saved them when the New Rochelle studio burned to the ground in 1913, keeping films in the pipeline while Edwin rebuilt a new, expanded studio. The fire made the papers and, never one to pass up good publicity, Thanhouser recreated the blaze for a fictional take on the real event called When the Studio Burned (1913), with studio stars playing themselves in a melodramatic rescue scenario.

Edwin and Gertrude sold the studio in 1912 and Charles J. Hite, a Chicago film distributor, took over as manager, continuing the studio’s commercial and creative expansion. But when Hite died in car accident in 1914, the studio floundered without leadership, losing talent to Hollywood and falling into formulaic filmmaking, before the new owners lured Edwin back. It took him time to adjust to the new industry paradigm but his commitment to both quality and ingenuity persevered in such films as Crossed Wires (1915), a thriller built around the novel use of the telephone and innovative dramatic effects. With their stars heading west, Thanhouser turned to new talent, including renowned Broadway actress Jeanne Eagels. Two of her Thanhouser films survive: The World and the Woman (1916), with Eagels as a prostitute turned faith healer and Fires of Youth (1917), which survives only in a shortened version. They are among the only film records that exist of the legendary actress.

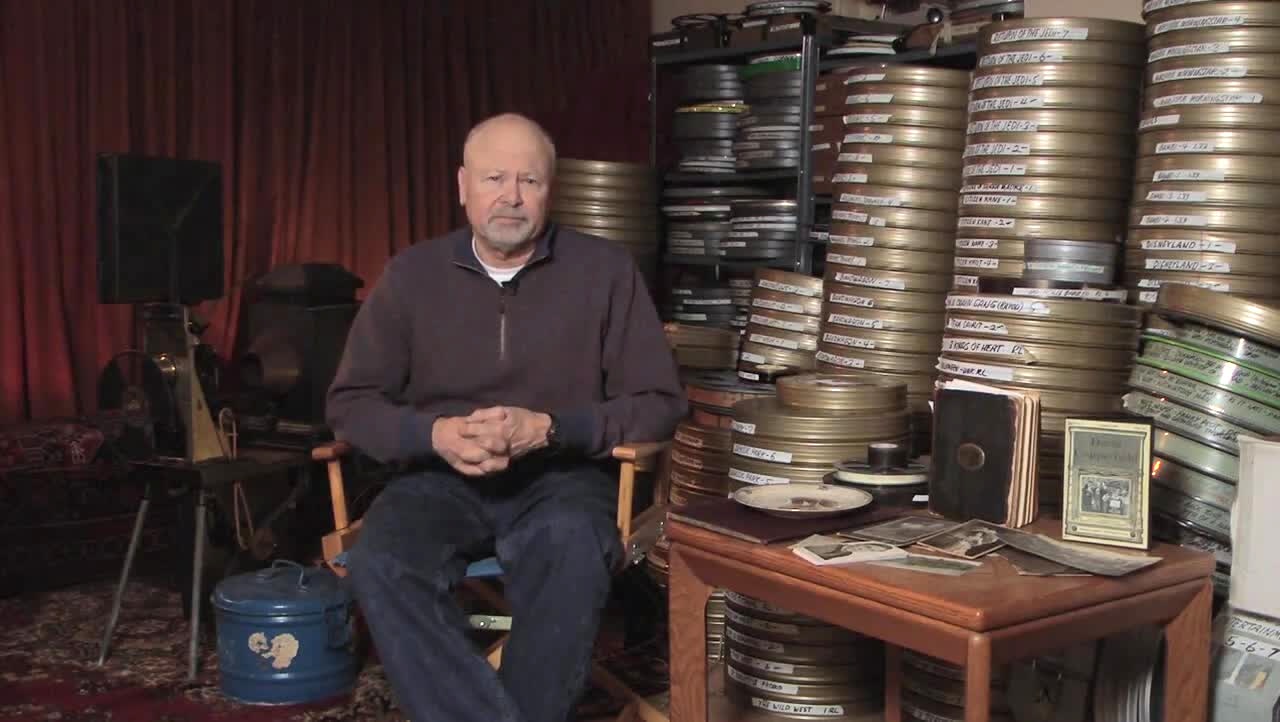

With Hollywood dominant as the center of filmmaking, Edwin recommended that the studio either move west or shut down. The owners chose the latter and when the studio shut its cameras and kliegs off for good, Edwin burned the entire library of nitrate negatives rather than pay storage costs; there was no foreseeable market for them in 1918 and apparently he had no sentimental attachment to his films. All that survived were the odd film prints found and saved by collectors and archives.

We can thank Ned Thanhouser, grandson of founder Edwin, for keeping the Thanhouser legacy alive. He believed that the Thanhouser legacy lost to time, so when he saw the Thanhouser logo on a silent short playing on television in 1985, he began searching for more, contacting film archives to find whatever remained of the 1,000 movies produced his grandparents’ company and formed a non-profit organization to document the company’s history and help preserve the company’s films. His website is a boon to silent film historians and fans of silent movies alike, featuring a definitive history of the company, an exhaustive accounting of the films and notes on the actors and employees of the studio.

The documentary The Thanhouser Studio and the Birth of American Cinema is both tribute to the studio’s legacy and a welcome addition to the history of cinema in its formative years. And for fans of the silent era, it serves as an introduction to one of the greatest studios of the twenties that has yet to receive its proper due. A century later, the Thanhouser brand still stands for high production values, sensitive direction, intelligent stories and fluid, energetic storytelling.