Jia Zhangke’s A Touch of Sin, a film that casts a cold, violent lens on Chinese corruption, opens with a scene set on an empty highway. A lone motorcyclist rides past the camera before being stopped by three men. In the background stands a bridge, only half-built, failing to connect the two sides of a canyon. The visual detail is easy to lose sight of; a triple murder that occurs seconds later calls more attention to itself. But it’s the kind of detail that British writer and director Patrick Keiller would probably, and rightfully, seize upon to help explain the entire film. Because the unfinished bridge, age-old symbol of corruption, is in fact an emblematic image for A Touch of Sin, a film that examines the emotional disconnect and social perversion caused by China’s nefarious politics. In that opening scene, the truth lies hidden in plain sight, in the landscape, a basic fact about our world that Keiller never tires of repeating.

Keiller is perhaps best known as the director of the “Robinson Trilogy,” his series of essay films filled exclusively with still shots of buildings, fields, compounds, roads, shopping malls and factories, over which a narrator (Paul Scofield in 1995’s London and 1997’s Robinson in Space; Vanessa Redgrave in 2010’s Robinson in Ruins) reads a mix of essay, memoir, and travelogue touching on industrialism, capitalism and the deterioration of cities. These are not, it should be said, easy films to watch in any traditional sense. They are dry and knowingly so. The narration owes as much, if not more, to academic style and bureaucratic precision than poetry or literature, leading to passages like the following: “Port traffic continues to increase. Exports have increased fivefold since 1965, most rapidly in the late seventies when North Sea oil was first exported. Imports have fluctuated but overall have risen by more than a fifth.”

But the three films are also, in their stubborn adherence to a rigid form, quietly subversive, helping to undo the ways we have come to instinctively view and interpret films. Ever since Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky coined the phrase, it has become common, almost clichéd, to think of filmmaking as “sculpting in time.” The basic expression, if not Tarkovsky’s actual theory behind it, reflects the way we naturally think about movies: as vehicles for our stories, which document changes over time. Just this summer, in the New York Review of Books, Martin Scorsese confirmed this primary element of film, quoting James Stewart’s definition of the movies as “pieces of time.”

Watching Keiller’s work and reading his essays, collected in the newly released book, The View from the Train, inverts this view of cinema. For Keiller, the locations he shoots, which inspire his scripts (a visit to a town might lead the narrator to tell of the protest that occurred there and maybe also the famous author who lived nearby), are the containers for stories, for history. By explicitly and repeatedly putting an emphasis on these places, Keiller compels us to consider movies as an examination of space rather than time.

Keiller’s preoccupation with space, as reading The View from the Train makes clear, is grounded in philosophical and political concerns. Time and again he looks at how ideas and ideologies stamp themselves on our lived environment. In London, he shows us the image of a skyscraper’s blown-out façade, the result of a car bombing carried out by the IRA. It’s our architecture, our terrain, Keiller implies, which bear the imprint, often tragically, of our beliefs and our stories.

In his 1998 essay “The Dilapidated Dwelling,” Keiller also grounds his attention to our environment in Heidegger’s notion of dwelling, a concept that emphasizes the core stability of physical spaces. “Let us think for a while of a farmhouse in the Black Forest,” Heidegger writes. This ideally constructed structure, he continues, provides firm grounding for a multi-generational story: “[the home] did not forget the altar corner behind the community table; it made room in its chamber for the hallowed places of childbed and the ‘tree of the dead’—for that is what they call a coffin there; the Totenbaum–and in this way it designed for the different generations under one roof the character of their journey through time.”

This notion of dwelling, Keiller admits, is both conservative and nostalgic. But it’s also the most radical explication of Keiller’s vision of the world, one in which history and personal narratives are best deciphered by examining the spaces that contain them. As Keiller’s narrator says in Robinson in Ruins, repeating a phrase from London: “If you look at the landscape long enough, it will reveal the molecular basis of historical events.”

If this makes for a consistently illuminating way of thinking of philosophy and politics, it’s equally fascinating when translated to Keiller’s films. In their own way, they also draw equally from Heidegger, who argued that art’s power grows from its ability to open up worlds; Van Gogh’s painting of a worker’s worn and dirty boots, he famously wrote, tells the story of a household, a town and a particular culture.

Keiller’s method is an extensive application of such thinking. In Robinson in Space, shots of different locations inspire tales and statistics about the health of England’s docks, Dante, Milton and Wiccan worshippers, just to name the bare minimum few. As he repeats this process from shot to shot, a collage effect occurs. In this respect, the final product closely resembles the free-wheeling eclecticism of Laurence Sterne or the scope of W.G. Sebald, both of whom used the power of digression to interconnect widely divergent time periods, people and stories. Yet Keiller’s films are grounded firmly in historical fact and real world locations, and so over time they lead us to also examine our own surroundings differently.

When taken specifically as an inspiration to alter our vision of other films, Keiller teaches us to look for the stories that are hidden in the details of a movie’s landscape. This isn’t about seeing what isn’t actually there. It’s about detecting what lies behind the explicitly visible. To take a recent example, in Before Midnight, as Jesse, Celine, and the other characters chat philosophically about time and aging, the Greek setting around them tells a grander version of the same story; it is, after all, one of the places on earth where the widest range of history is physically present for examination.

Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours functions in a similar way. While telling the story of a budding friendship between Johann (Bobby Sommer), a museum guard, and Anne (Mary Margaret O’Hara), a Montrealer visiting Vienna to take care of her dying cousin, the film attempts to emulate Bruegel—one of the innovators of the landscape painting, coincidentally enough, and a figure who the film spends much time considering—by letting its central subjects disperse into the crowd of their city. Even during scenes focused on Johann and Anne, Cohen cuts away regularly to sights in Vienna: pedestrians on the street, patrons at a bar, trash on the ground, and some of the city’s more recognizable buildings. In slow increments, Cohen provides a well-rounded vision of Vienna, displayed during a cold and grey winter, filled mostly with mundane events—people passing the time and running errands. And even so, the city emphasizes the loneliness of Johann and Anne, their weariness standing in contrast to even the slight bustle of Vienna.

In both Before Midnight and Museum Hours, the spaces in which characters act become valuable subjects of inquiry, with as much to say about the protagonists, their context, and their mindset as other elements in the movie. Keiller is more radical, of course: he offers us films with all the other elements cut out. Writing about some of his early photography, Keiller describes this method, which has defined his work throughout his career:

This visual material deliberately depicts places that are nearly or altogether devoid of human presence and activity, but which because of this absence are suggestive of what could happen, or what might have happened. … The aim is to depict the place as some sort of historical palimpsest, and/or the corollary of this, an exposition of a state of mind.

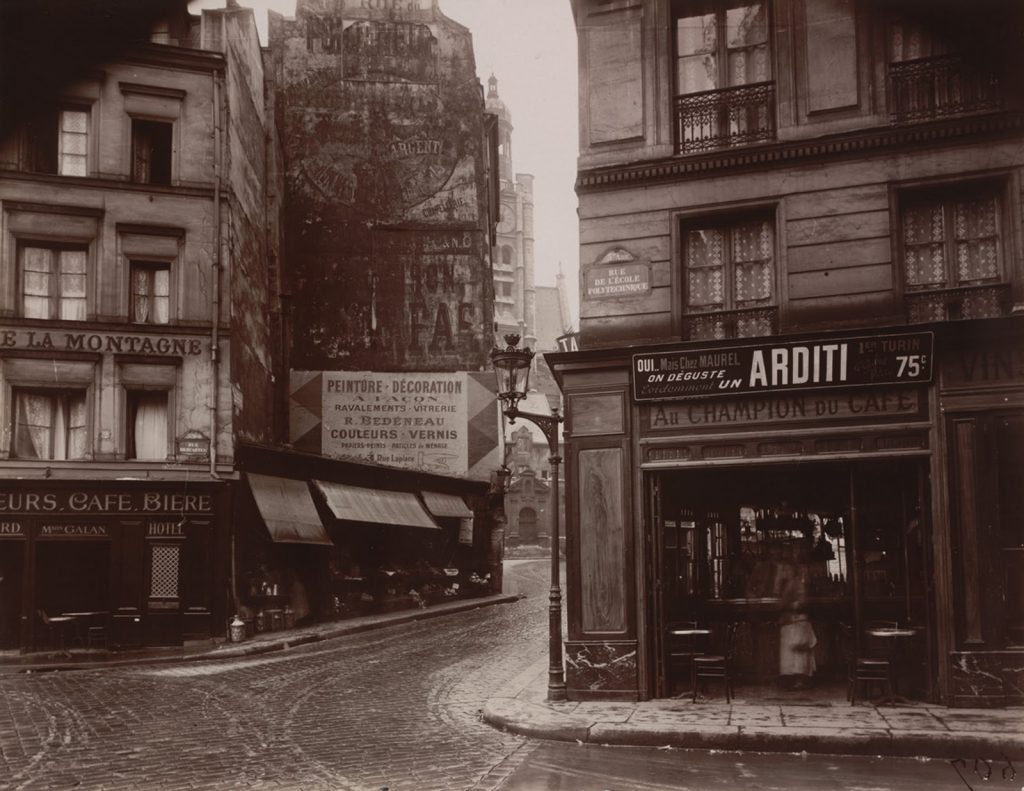

While the visuals Keiller presents us with are always superficially bereft of any meaning, the narration he writes digs beneath them to show all the stories and all the events that exist there implicitly. And if the films themselves never fantasize about potential future events, the visuals lend themselves easily to such speculation. Describing the photography of Eugène Atget, Keiller also gets at the power of his own work in this respect: “They reveal an ambiguity, a potential for transformations both subjective and actual, in ordinary locations.”

This transformative power that Keiller’s work forces us to notice is in fact intrinsic to film, a medium with the ability, as Keiller quotes Louis Aragon saying, “to endow with a poetic value that which does not possess it.” That effect can occur in real life as well, of course, though often when it does we find it has been foreshadowed in film. Watching Tom Cruise drive through the empty streets of New York to an abandoned Times Square in Vanilla Sky is eerie, but it takes on a completely new context for a New Yorker who wandered lower Manhattan when the power was still out in the days after Hurricane Sandy.

“Most of us spend much of our time in spaces made and previously occupied by other people, usually people of the more or less distant past. We might reasonably expect our everyday surroundings to feel haunted but, by and large, they don’t. Haunting is still relatively unusual.” So begins “The Robinson Institute,” Keiller’s best essay in The View from the Train. But his films in many ways put a lie to what he writes. They are, after all, documents of how haunted our world actually is, proof of Oscar Wilde’s dictum from The Picture of Dorian Gray, quoted by Keiller in one of his essays: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.”