Joy-hating is so hot right now. On Twitter, people favorite articles without reading them and criticize movies that haven’t been released. For personal brand promoters, it’s important to contrast extreme obsession with personal disgust, which does indeed make one stand out but essentially slams the door on give-and-take discussions. Why spend time on second viewings if you absolutely love some films and hate others? In the age of hyper-hyperbole, people joy-hate movies that don’t perfectly align with one’s vision of how the world should be. But perhaps brand-promoting trolls need to explore the space between “the best thing ever” and “the worst thing ever.”

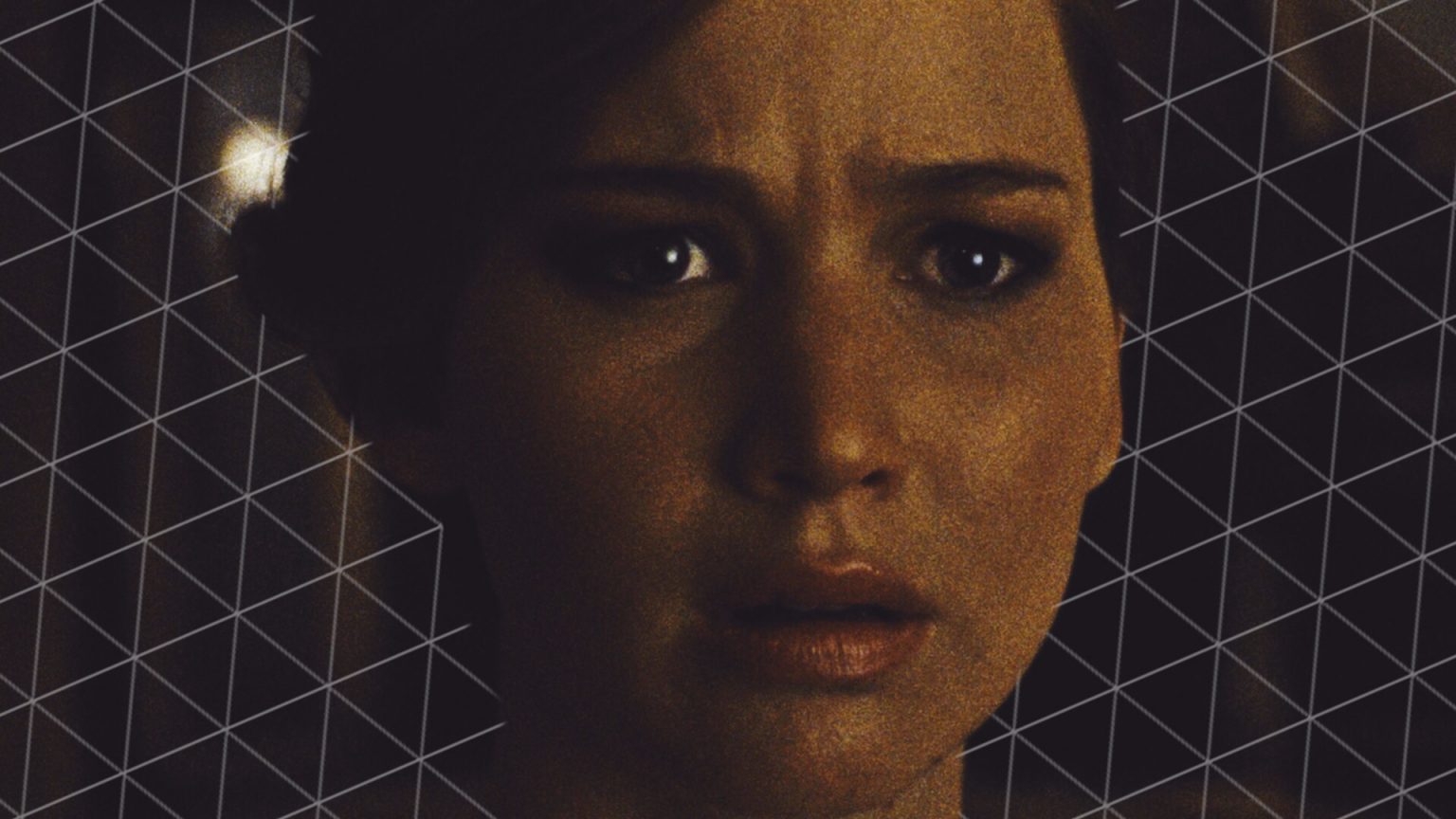

The unapologetic joy-hater misses opportunities for alternative readings. In 2017, Darren Aronofsky’s mother! offended many critics and moviegoers with its violence and perceived misogyny. A newborn is killed, and the mother, Jennifer Lawrence’s character, is subsequently assaulted. But are the visuals meant to be interpreted literally? The metaphors suggest that mother!‘s surreal narrative takes place in the mind of Javier Bardem’s “Him,” a man that’s navigating his own creative hell. Lawrence’s character, a muse, figuratively paints the walls of the artist’s mind, thus inspiring new characters and ideas that ultimately receive more attention. Does the artist emotionally abuse his wife? Or does the artist dismiss his original inspiration to explore new concepts? Not everyone will appreciate mother!‘s aesthetic, but the metaphors are indeed important when interpreting the visuals and dialogue. Despite the film’s overt surrealism, many see only emotional and physical abuse. But consider this: if a writer finds inspiration from one single idea, is that same writer an abusive person if he or she decides to explore a new creative direction? A film like a mother! allows for different interpretations upon a second viewing — unless you’re someone that says “I don’t have time.”

In recent months, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread has been mostly well-received by critics. So, when The Week published an article that challenged the film’s worth, it naturally sparked discussions about personal preferences and joy-hating films. Phantom Thread isn’t factually good or bad; it’s a cinematic experience. And it’s ok to not feel impressed, just like it’s ok to enjoy the filmmaking aesthetic. In general, joy-haters often place more value on their brand than patient viewing, because love and hate go a long way on social media. Love and hate mean clicks and/or attention. That’s part of business, that’s part of the game. And many people can articulately and objectively back up strong movie opinions. In contrast, the impatient moviegoer leaves the theatre, criticizes narrative points without fully understand the context, and then nails themselves to a cross on a high hill, screaming into the internet void to make sure everyone knows they have an opinion.

In the past, the best critics valued an objective approach. Today, many young writers brand themselves as film critics but focus mainly on movies and performers that make them feel good. Some even profess sexual attraction for celebrities on social media but still want their opinions to be taken seriously as professional film critics. Just as digital media changes, film criticism most certainly will too, but there’s a distinction between film critics and online writers that cover their favorite movies and celebrities. And with identity politics being emphasized more, there’s more online joy-hating from people who actively promote a LOVE-HATE personal brand. But aren’t movies supposed to challenge us to re-examine how we view the world?

For example, an Oscar-nominated film like Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri doesn’t necessarily offer a feel-good experience, but it’s not supposed to — it’s meant to spark discussions about society. But if one focuses on personal politics first, that same individual can easily miss the subtext or, in the case of Three Billboards, the satirical dark humor. In general, people don’t slam the Coen brothers’ dark comedies because those films lean more towards surrealism than everyday realities. If I’m from Fargo, though, which I am, should I be offended by Fargo and all its absurdity? Or is there a larger point being made?

Movies are investments. And some moviegoers understandably don’t want to invest time in films that don’t offer easy answers or don’t make them feel good. But whether you’re a cinephile, a film critic, or someone that just really loves writing about movies, it’s beneficial to invest time in polarizing films. Promote movies you love, but challenge yourself (and others) to look beyond biases to consider different interpretations. And if joy-hating movies improve your personal brand, then take a moment to consider that active trolling reveals more about personal insecurities than bad filmmaking.