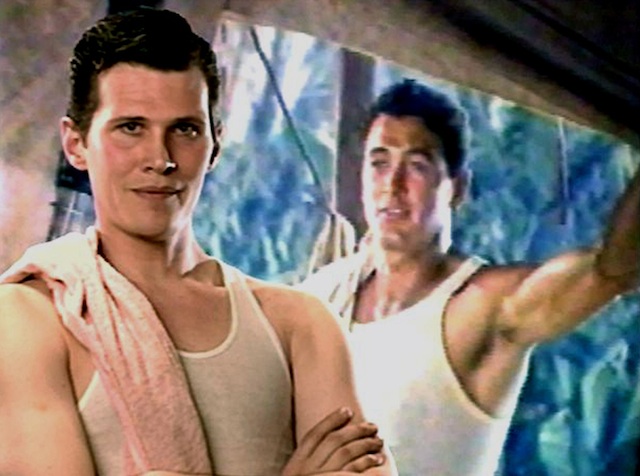

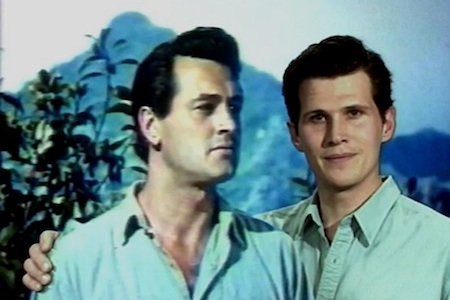

Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is a collage film, in which the ‘found footage’ is the star. It is revisionist film history that re-examines Hudson’s films in light of what we now all know about him—namely, that he was gay and died of AIDS. Rock is a unique paradox—the paradigm of screen masculinity who also happens to be gay. The fictional construct that was Rock Hudson becomes the text that can be read and re-read in a variety of ways—but all roads lead to Rome. Rock Hudson was a prisoner of, as well as a purveyor of sexual politics and stereotypes. He is a prism through which sexual assumptions, gender-coding, and sexual role-playing in Hollywood movies and, therefore, by extension, America of the ’50s and ’60s can be explored. In a sense, it is Hudson’s sexuality that is the real auteur of his movies—just as his closeted-ness was the icon all America was worshipping.

* * *

When I was asked by a film festival director for a statement of the “director’s intentions” (directors are usually the last people you should believe when it comes to talking about what their films really mean), that’s what I wrote. I’ve been using it as publicity material ever since. So now it’s part of the official story. But nothing quite that grand was on my mind when I started working on what turned out to be Rock Hudson’s Home Movies.

* * *

Background—In the early ’60s when movie houses were still movie houses—not multiplexes, not parts of shopping malls, not afterthoughts, not subterranean holes in the ground where the subway hurtles by ten feet away—there were about a dozen movie palaces, formerly legitimate theaters, on 42nd Street that played old double features to a fairly unselective clientele, charged minimal admission prices, and were open round the clock. This was a place you could catch up on B-movies from a few years back and certainly all the Westerns you ever avoided. At one of these theaters (they had names like “Liberty” and “Victory” and “Apollo,” names which belied their skid row status and suggested days of former glory), I saw Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly. In the film, a greedy young psychopath of the female variety, who always wanted to know what was in the box, that mysterious thing that everyone in the film is after, is finally alone with the box and is ready to open it. She unties one of the straps. From the recesses of the darkened balcony someone yells out, “Don’t open the box!!!” She opens the box, which contains something like an atom bomb. This modern-day Pandora goes up in flames. It’s hard to convey the chastising but self-satisfied tone in which the voice in the theater calls out in response, “I told you not to open it!”

This is before the days when audiences would scream out, “Kill the bitch!!” and well before the days when black audiences would scream, “Kill the white bitch!!” It was a more innocent time.

* * *

1993—They are trying to turn the grind houses of 42nd Street into legitimate theaters once again. Walt Disney Productions has been awarded a low-interest loan to the tune of $29 million by the city of New York to restore the jewel-in-the-crown theater, The New Amsterdam, where Ziegfeld Girls once paraded down artfully arranged staircases for New York society. The live version of Beauty and the Beast (Disney, not Cocteau) is the most expensive musical ever put on Broadway and will very likely be one of the most successful as well. Perhaps in the not too distant future every one of these theaters will be occupied by a live musical version of a hit animated Disney film.

Needless to say, legitimate theater producers, who have been putting on productions for years, are outraged at the city’s sweetheart deal with Disney, as if Disney doesn’t have enough money to retire the American deficit and still have spare change left over for a large bucket of popcorn.

* * *

I personally like the idea of moviegoing as a contact sport. When I’m not totally engrossed in a watching a film, I find myself talking back to the screen. Pity the friend who accompanies me. Well, maybe it’s just in a whisper, maybe it’s just in my head, but there are two sound tracks going on all the time. The one from the film and my running commentary on it. Which makes watching films on TV much more democratic. In the privacy of my living room I can speak my mind aloud and at the same decibel level as the film I’m watching. The invention of the VCR turned this active approach to film criticism into an indoor sport. You can gripe about the dialogue, the sets, the angles, the acting, the plotting, at your own pace. If you wanted to (I never did) you could roll back and rewrite your barbs until you got it right, until you found the perfect retort, le mot juste. In a sense it’s almost the antithesis of The Rocky Horror Picture Show phenomenon, where the script is Holy Writ. You can be your own Greek chorus commenting on some other filmmaker’s tragedy. You, combative viewer, can be the antistrophe.

* * *

1982. Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid. When I first saw this movie, I wished that I had made it. As far as incorporating elements from the films one loves and consciously making them part of one’s work and esthetic, no film has gone further. What I found most extraordinary about it, aside from the trickery of the actual making of it, trying to match the decor and texture of existing movies with the one that is being made, is that the movie clearly was written with one hand on the typewriter and the other on the VCR, with piles of videocassettes stacked nearby. Clearly, the writers were looking at dozens of movies as they were writing, to see which lines of dialogue could be lifted, appropriated, and woven into the script they were fashioning and still have them refer to the new situations they were devising—which shots from which films could be incorporated into their own film and so on. This kind of patchwork process appealed to me greatly. Partly because of my background as a film editor and partly because of my esthetic as a pasticheur (steal from everyone, but wipe the fingerprints off!!), I found the film an extraordinary step in the direction of, well, something or other—a valentine to the genres you love coupled with a sobering awareness that to try to duplicate them would be ludicrously anachronistic.

I personally like the idea of moviegoing as a contact sport. When I’m not totally engrossed in a watching a film, I find myself talking back to the screen. Pity the friend who accompanies me. Well, maybe it’s just in a whisper, maybe it’s just in my head, but there are two sound tracks going on all the time.

I liked the idea that an existing text could be pulled apart, detached from its intended context, and re-woven into a new text with its meanings changed or shifted, leaving its actual essence untampered with. I liked also the idea that clearly the filmmakers were thinking as they were making their work (they want the seams to show), and you can see their thought processes nakedly on the screen. This was back in 1982, a decade before every hack journalist would casually use words like “post-modernist” and “deconstruction” to describe everything from beer commercials to Almodòvar to The Flintstones. Just as those words have lost, through mind-numbing overuse, their meaning, so was the shock of the seeing a movie like Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid made in Hollywood, a realm in which such polysyllabic words have to get special visas. So what was the film, then, if the makers didn’t have the vocabulary to describe the process? Perhaps they were just plugging into the zeitgeist. After all, post-modernism describes a process. It is not a formula for making work. Deconstruction is done after the fact by the spectator, not beforehand by the publicist.

Well, zeitgeist or no, it’s certain that the writers could not have come up with such a concept without the availability of VCRs or VHSs of the movies they drew on. Ten years earlier, it would have been unthinkable that such a movie would even be thought of. Ten years later is there anyone who is not doing it?

In 1984, I show parts of the film to a class I’m teaching. One of the students, a recalcitrant troublemaker from the beginning of the semester, raises his hands and says, “So what? It’s stupid.”

* * *

Four years ago, I am staying at a friend’s house in La Jolla, California. In addition to the lovely weather and the beachfront house, he has cable TV, which I didn’t, at the time. While channel-surfing (this would have to be the right word because right outside the house is the prime surfing spot in San Diego), I see a low-budget ’50s film about runaway teenage bad girls on a reform school-type work farm. At the bottom of the screen are the silhouettes of what are clearly movie-theatre seats. Facing the screen, watching the image just as we the spectators are, is a young man, flanked by what looks like a talking gum-ball machine and some low-rent space-age robot that looks like it’s built out of spare kitchen appliance parts. (Sometimes there is also a talking vacuum cleaner who also partakes in the chatter.) The three of them are heckling the actors on the screen and rewriting the dialogue as well as blasting holes in the implausibilities of what we see on the screen. “Oh, boy!” I think. “This is for me.” But, after the initial delight that such a thing exists at all, the charm wears off. A little bit of this stuff goes a long way. There are lots of predictable cheap shots and the humor, such as it is, is the kind of stuff you came up with when you were in high school. Or when you were on drugs and thought that everything you said was hilarious. It’s still on the air and it’s called “Mystery Science Theater 3000.” Mostly they have Mexican horror movies and Japanese monster movies dubbed into English. The point? Everybody’s a critic. Also, no piece of film is so worthless that it can’t be re-cycled and commented upon.

The following year I decide to get basic cable myself. One night, after midnight, as I was idly dialing from one channel to another (in New York, we have a couple of public access channels that program fairly explicit sexual material for restless and/or horny late-night viewers), there was a show that caught my attention. Clips from movies, Hollywood and otherwise (mostly pornos, actually), arranged haphazardly with no apparent narrative direction to it—all the clips are of young men in various states of undress and it soon becomes clear that the guiding sensibility is a predilection for male teenagers in white Fruit of the Loom briefs, a combination that does not interest me nearly as much as it does the man who slaps the show together every week. We never see him but we hear his voice commenting endlessly with a distanced but not disinterested irony about what we’re watching.

At first, again, I think this is great, and for several weeks running make sure to watch the show. It is called CCTV—Closet Case TV—and the unseen host is Rick X, apparently an English teacher at a local university who, to protect his job, has adopted this nom de television. To throw the censors off his trail, he calls it Christian Community TV, but I don’t think anyone is fooled. Apparently he’s been on the air for 16 years but I’ve only just caught wind of it.

Maybe I should get out more.

* * *

Along the same lines. With the proliferation of talk shows on American television in which disgruntled family members can talk about who did what to whom, where women can argue with their boyfriends who cheat on them with their girlfriends, where transsexuals can talk about how womanly they feel and give the studio audience tips on how to please a man, in front of an audience of unseen millions, it was bound to happen. One of the fledgling cable channels produced their most successful show yet, “Talk Soup.” The format is simplicity itself. The smart-aleck host presents clips from and comments on the bestexchanges on that particular day’s TV talk shows. In other words, you don’t have to sit through the whole opera—you can just have the highlights.

The show is so successful that it spawned more unholy progeny, “Pure Soap,” in which plot synopses (so dear to the hearts of college students cramming for exams) and clips from that day’s soap operas are given and commented upon.

All I know is, in the future, when everyone in America has their own talk show on one of the 500 cable channels that we’re all eagerly supposed to look forward to, I want one, too.

It seem that everyone is doing it, commenting on popular culture while creating it at the same time—the snake eating its tail. Everyone is into deconstructing the all too obviously deconstructible. It’s become a national pastime. Recently there was a made-for-TV movie called Deconstructing Sarah. I have no idea what it’s about but the fact that that word itself can work its way into the TV listings, with the expectation that viewers will know what it means, should give practitioners of critical theory pause as to how easily complex ideas can be popularized and debased. Actually, in the ’70s there was a slew of would-be elegant soft-core pornos with pinky-in-the-air titles along the lines of “The Coming of Clarissa,” and “The Taking of Melanie.” For some reason, an important element to this sub-sub-genre was the use of the gerund in conjunction with an upper crusty woman’s name. I guess the two together was supposed to bestow a touch of class on a reviled genre.

* * *

The host of “Talk Soup” was rewarded for his successful wisecracks with his own major network talk show where celebrities are invited to plug their current movies or concert tours, all in the guise of entertainment, while informing an already much too well-informed public about celebrity activities. In other words, the culture, such as it is, running on empty, is feeding on itself endlessly and producing more and more debris. TV shows about TV shows, entertainment about entertainment—it’s a self-proliferating medium which can’t prevent the cancerous cells from replicating. But, the problem, as always, has been in whose backyard do you bury the plutonium?

All I know is, in the future, when everyone in America has their own talk show on one of the 500 cable channels that we’re all eagerly supposed to look forward to, I want one, too.

* * *

If you believe that mechanical inventions have no political relation to the times in which they’re invented, skip the next section.

I couldn’t work, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t write (even sitting up was too strenuous an activity, thinking was impossible). Sometimes I was too sick even to watch TV. Yes, that sick!! Often I would tape whatever junk was on at night and watch part of it the next day. Or sometimes, on a good day, that is, if I felt well enough to walk, I’d go to the nearest video store, just a few blocks away, come back and collapse with a pile of videos to fill up my days, while waiting to get better. At one point it occurred me—how convenient and coincidental that the invention and widespread dispersal of VCRs and VHSs coincides simultaneously with the worldwide spread of AIDS and other immune system disorders.

Without getting into the details, several years ago I was quite ill. For the period of two and a half years, I was virtually bed bound. I would feel OK for a while, but never really well, and then would relapse and have to spend two or three days in bed. I had been, prior to that time, taping movies on my VCR and had a library of some of my favorite films, as well as, like all libraries, film or book, many items that I had never looked at. It was the only thing I could do during the day—watch films. I couldn’t work, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t write (even sitting up was too strenuous an activity, thinking was impossible). Sometimes I was too sick even to watch TV. Yes, that sick!! Often I would tape whatever junk was on at night and watch part of it the next day. Or sometimes, on a good day, that is, if I felt well enough to walk, I’d go to the nearest video store, just a few blocks away, come back and collapse with a pile of videos to fill up my days, while waiting to get better. At one point it occurred me—how convenient and coincidental that the invention and widespread dispersal of VCRs and VHSs coincides simultaneously with the worldwide spread of AIDS and other immune system disorders.

In earlier times, death was much quicker and people didn’t expect to be amused between the time they got sick and the time of their death. The interval between the two, then, was usually shorter but long-term chronic illnesses are definitely the wave of the future. In my visits to many, many doctors I was told by several of them that they expected in the next decade (that’s this decade now) to see an explosion of immune system disorders—nothing quite as dramatic or as horrible as AIDS, but many more immune system dysfunctions as a result of the lives all of us are forced to live. Whether or not these diseases have subsequently appeared, I don’t know. They certainly have not been written about in the papers of official record. I do, however, personally know a lot of people who are or were quite sick with long-term ailments, many more than people my age knew, say, 20 years ago. And with the depletion of the ozone layer and subsequently much more exposure to ultraviolet rays, we can expect to see proliferations of many more cancers, and immune systems disorders than we have seen in the past. AIDS is just the beginning of viruses running amok, becoming stronger than the antibiotics that we used to depend on to knock out the alien microbes that invaded us. If the roaches, rats, and pigeons will take over the earth, so will as yet unnamed and still-developing viruses decimate populations in ways that are still unimagined. This is neither doomsday ranting nor Malthusian prophesying. As the human race has been weakened by antibiotics, by processed foods, by polluted atmospheres and cancer-producing environments, so other organisms such as whatever it is that causes AIDS grow stronger. OK. Let me get off this particular tangent. After all, I only took biology in high school, so I can’t even claim to know what I’m talking about.

However, the paranoia of having an illness that had no identifiable source or even, at the beginning, a name made me realize that VCRs had to be invented to becalm an already subdued ever-growing army of weak and debilitated people—but for what purpose? From committing mass suicide? From feebly voicing their discontent with the medical status quo of the way medicine is practiced and diseases treated? A disabled segment of society soothed into further passivity by watching Walt Disney movies, Die Hard, Terminator 2 until the magnetic stock wears off the surface of the vinyl tape. VCRs were designed, if not by intent, certainly by default, to take the burdens off family members and loved ones and distract one from the seeming hopelessness of one’s own ailment. A little bread, lots of circuses—rent two videos and you’ll feel better in the morning.

Perhaps Home Alone is the prophetic movie title of what may one day be called the concurrent age of AIDS and VCRs, a bed-bound population being comforted to the hum of best-selling rental video hits. Even when you can no longer participate in your own life, that shouldn’t prevent you from keeping up-to-date with disposable popular culture. It seems clear that religion is not the only opiate of the masses. But although Benjamin might have predicted the uses and applications of the VCR, Marx certainly couldn’t have.

I remember, at the time, being incredibly grateful at the time for the invention of the VCR, the electronic babysitter.

* * *

While I was sick (since it lasted so long, it was, de facto, a transforming experience in my recent life and, also, in my work), I was too sick to exercise. I decided to buy an exercycle. Because the activity itself was so excruciatingly boring, I would watch movies for the 25 minutes a day that I cycled, when I actually did it. At one point, I was watching Victor Fleming’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941), a film I’d never seen before and which impressed me with its nonchalant and uncensored kinkiness, especially since it was made by MGM. In one Hyde fantasy scene, Spencer Tracy has good girl Lana Turner and bad girl Ingrid Bergman strapped to his coach as horses while he is gleefully whipping them. But that’s another story.

There’s a scene in which Lana drags Spencer off to a museum and points to a pint-sized replica of a famous sculpture (this was, mind you, well before the days museum gift shops existed and became one of the main sources of direct income for museums). Lana explains that the original is in the Louvre and it’s called Winged Victory. Spence, without missing a beat, quips, “What’s the point of being victorious if you haven’t got a head?” Lana snaps back, “What’s the sense of my acquiring culture if you’re not going to pay attention to me?”

Well, that pretty much lays it on the line, doesn’t it? I also distinctly remember her saying, “I like knowing about art. It gives you something to talk about.” But I could never find that line again, even though I went through the movie two times. Was I hallucinating from the heat and my accelerated heartbeat as a result of my frantic exercising? In any case, on that day, the idea for Rock Hudson’s Home Movies was born.

At one point, I was watching Victor Fleming’s ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ (1941), a film I’d never seen before and which impressed me with its nonchalant and uncensored kinkiness, especially since it was made by MGM. In one Hyde fantasy scene, Spencer Tracy has good girl Lana Turner and bad girl Ingrid Bergman strapped to his coach as horses while he is gleefully whipping them. But that’s another story.

There’s a scene in which Lana drags Spencer off to a museum and points to a pint-sized replica of a famous sculpture (this was, mind you, well before the days museum gift shops existed and became one of the main sources of direct income for museums). Lana explains that the original is in the Louvre and it’s called Winged Victory. Spence, without missing a beat, quips, ‘What’s the point of being victorious if you haven’t got a head?’ Lana snaps back, ‘What’s the sense of my acquiring culture if you’re not going to pay attention to me?’

I thought it would be interesting to put together a compilation, with some kind of minimal commentary, of scenes about art and artists as they are represented in Hollywood movies, exploring the contradictory and conflicting attitudes in which artists and art seem to be revered but yet reviled—almost within the same breath/frame. I got excited about the idea and jotted down about two dozen titles which quickly came to mind, from which I could extract scenes.

I also excitedly scribbled down half a dozen other ideas, examining modes of representation in mainstream films, one of which turned out to be Rock Hudson. It seemed more urgent to do Rock Hudson because it meant dealing with gender issues, role-playing, homosexuality, and AIDS. Also, the idea of an invented, “fictitious” autobiography interested me. It provides a structure on which to hang a variety of different themes and still permits you to keep them cohesive.

At that point in my life, various projects had fallen through, or were in the process of falling through. I had also been quite sick, again, after a relatively long period of fair health, for about two months. I thought, at that time, that there was a strong possibility that I might never be physically capable of working again the way I had in earlier years, that I might never have the strength to do another feature. I thought that this kind of compilation was something that could be done as a mildly low-level work involvement. I could more or less transfer scenes from one VCR to another VCR and then edit them. Simple.

It wasn’t.

One of the proposed projects was a video about illness as it’s depicted in films. Women are always depicted as hypochondriacs and complainers, even when they have serious ailments. Men suffer, mostly silently, but better yet, they don’t get sick at all. They carry on and then drop dead. If they have mental illnesses, and they rarely do in films, it’s mostly amnesia. If you want more theories and surmises, an extensive list of film titles is available on request.

I submitted a hastily drafted proposal of the project, provisionally titled, ‘FBI Warning/Couch Potato’ Videos (Couch Potato Productions subsequently became the name of my company), to Bill Horrigan, the director of Media Arts at The Wexner Center of the Arts in Columbus Ohio, a small, private museum that is attached to Ohio State University, one of the largest universities in America.

Even though the museum is tiny by almost any museum standards, the Media Arts department was in the process of amassing tons of video equipment, partly because it is affiliated with the university. Bill said—sure come out and use whatever we’ve got. I went out there and started using the equipment even before most of it was there or hooked up, and way before the video studios designed to house the equipment had been built.

I should add, just as a footnote to the above, now that I am completely better, I don’t see my future as limited to such small-scale projects as Rock Hudson. When I say “small-scale,” I do not say it to deprecate the work. I am only referring to the fact that what it entails is just me sitting in front of an editing machine, with very few other people involved in the actual making of the project, and relatively little money to spend on the whole work.

The exercycle resides permanently in my closet.

* * *

After I finished Rock Hudson, a friend told me that there was a movement in London at the time that the VCR first became popular, in the early ’80s, of “scratch videos ,” in which people made their own compilations and showed them. I’d never heard of it before and certainly had never seen any.

* * *

Perhaps this is a long-winded introduction as to how and why I came to make Rock Hudson’s Home Movies. But it seems to me that the genesis of an idea is not always a straight line. When I first started doing the video/film (in several countries, it’s been released as a film—other places have shown it in its original video format), I don’t think I had a specific notion of what I wanted to do. I had written some notes—about 30 pages of loose ramblings, not unsimilar in tone or style to what you’re reading now. But when it came time to do the actual editing, I realized that everything I had written was way too long and could never fit in in between or with the clips I wanted to use. I realized, though, that I could, with a microphone, speak into the second audio channel while keeping the sound from the actual film clips on the first channel. What a discovery! To be able to write without paper, pen, or typewriter! What fun! The spur-of-the-moment remark would lead into another cut, which would suggest another way of structuring the next cluster of shots. It was an incredibly liberating realization and experience, writing without letters or a keyboard, writing in a style of seeming spontaneity.

Nor did I want the piece to have an academic flavor. I’m not much of a reader of critical theory (the only times I immersed myself in it was when I was teaching because I felt a nagging need to sound smarter than my students), and I certainly didn’t want to use the jargon—replete with a vocabulary no one ever seems to use in real-life but to which people seem addicted as soon as they start writing. Nor did I want it to be only for that (tiny) audience that was secretly initiated into fashion-driven argot, either. I wanted it to be accessible to a wider audience and, above all, entertaining. (As I get older, I realize more and more that there is a great deal to be said for films that can genuinely entertain. So this has become one of my unspoken goals in the creation of new work.)

But, in reality, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is a child of 15 or 20 years of critical theory. It may not be indebted to specific articles or theories but it certainly is indebted to theoretical approaches that have subsequently reached deeply into our culture—questions of gender-stereotyping, feminist and gay concerns about modes of representation, what an image means, and the different ways in which an image or words, or an image combined with words can be read. Nor could Rock Hudson have been made before the invention of that quintessential surplus capital leisure time appliance, the VCR.

In that sense, I am very pleased with having made it. I always thought of myself as very linear and locked into traditional forms. It pleased me to be able to use newer technologies and reinvent the purposes for which they were originally designed—in the course of which I realized that video is a much more gracious and relaxed format than film for something as personal and cranky as an essay. Creating an “essay” on film, at least these days, seems like a great deal of work (and money) for something that has such a relatively small audience willing to watch it.

But most of all, when I say that Rock Hudson could not have been made even ten years earlier, I mean in the sense that earlier a vocabulary had not been in place to articulate the concerns the piece deals with. Before the days of women’s liberation, I remember going to films with my then wife, and we would talk about how women were treated (we most certainly did not use the word “represented”) in Hollywood films of the time as opposed to the films o